NAVY FORCE STRUCTURE Sustainable Plan and Comprehensive

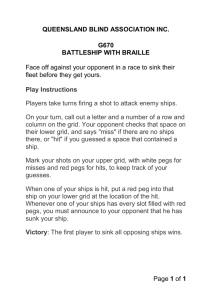

advertisement