GAO DEFENSE ACQUISITIONS Decisions Needed to

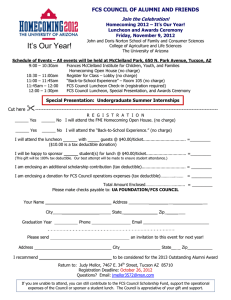

advertisement