SPECIAL OPERATIONS FORCES Opportunities Exist to

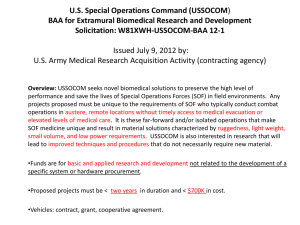

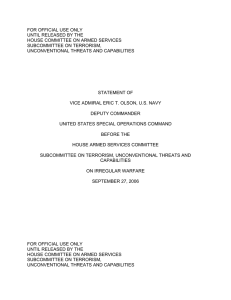

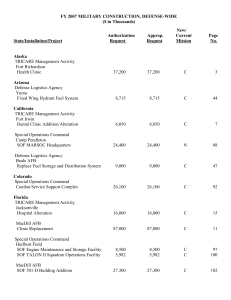

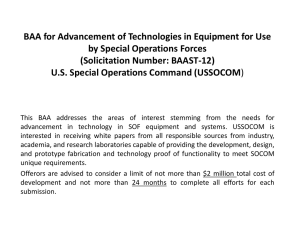

advertisement