GAO DEFENSE INFRASTRUCTURE Continuing Challenges

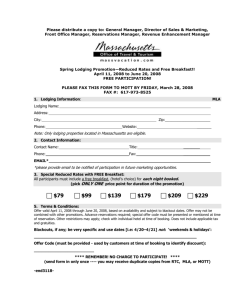

advertisement