GAO MILITARY BASE CLOSURES Opportunities Exist to

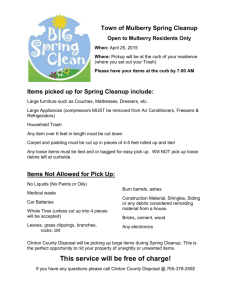

advertisement