GAO MILITARY BASE CLOSURES

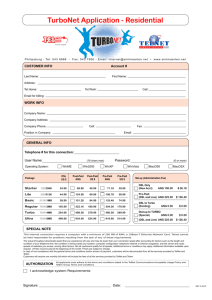

advertisement