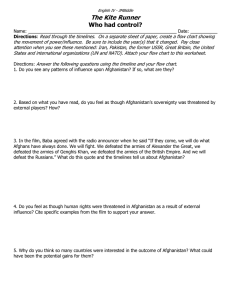

GAO AFGHANISTAN Key Oversight Issues Report to Congressional Addressees

advertisement