AFGHANISTAN Embassy Construction Cost and Schedule Have

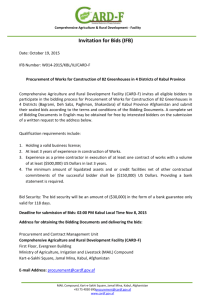

advertisement