CRS Report for Congress Colombia: Issues for Congress Connie Veillette

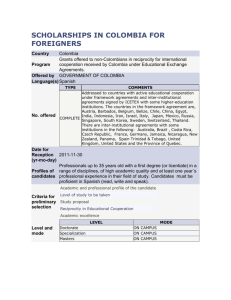

advertisement