CRS Report for Congress Colombia: Conditions and U.S. Policy Options

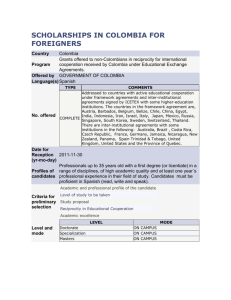

advertisement