CRS Report for Congress Andean Regional Initiative (ARI):

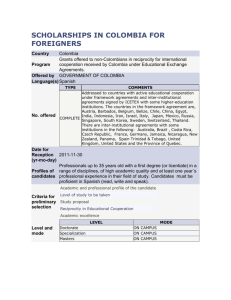

advertisement