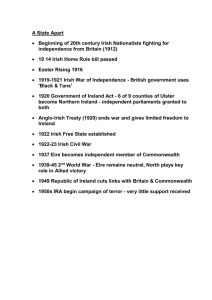

CRS Report for Congress Northern Ireland: Implementation of The Peace Congress

advertisement