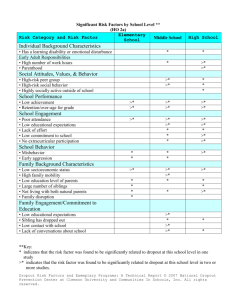

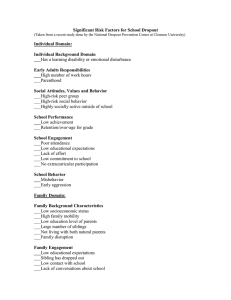

A Literature Map of Dropout Prevention Interventions for

advertisement