PKSOI Papers HARNESSING POST-CONFLICT TRANSITIONS: A CONCEPTUAL PRIMER

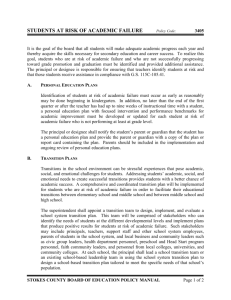

advertisement