Document 11049561

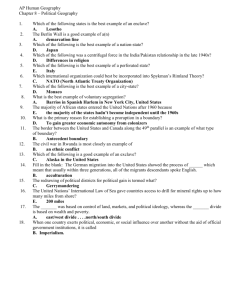

advertisement

.*»^o* ** Z lUBSAKIESl (9 HD2C ^-,s. iust" Mar j^ ALFRED P. WORKING PAPER SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT MANAGEMENT ISSUES IN NEW PRODUCT TEAMS IN HIGH TECHNOLOGY COMPANIES By Deborah Gladstein Ancona Sloan School, M.I.T. David F. Caldwell Leavey School of Business Santa Clara Universit^' WP 1840-86 November 1986 MASSACHUSETTS TECHNOLOGY 50 MEMORIAL DRIVE CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139 INSTITUTE OF _. MANAGEMENT ISSUES IN NEW PRODUCT TEAMS IN HIGH TECHNOLOGY COMPANIES By Deborah Gladstein Ancona Sloan School, M.I.T. David F. Caldwell Leavey School of Business Santa Clara University WP 1840-86 November 1986 To be published in Advances in Industrial Relations , Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, Inc., forthconing. MAR 1 9 1987 , The ability successful develop to new products will make to sales growth profits generated by new products & Hamilton, 1982). particularly introduction irnportant organizational industries, survival. issue the is expected to increase by one- high technology industries, technologies may be and companies For not is expected to increase by 50 percent is This need for new product development in new products of for During this time, the portion of total coopany third during the 1980s. is critical is Business experts note that the contribution which many organizations. (Booz, Allen new products solely the where the necessary for highly in conqjetitive introduction of new products, but also how to quicken the product development process (David, 1984). The growing inportance of the developnent of new products can pose difficult challenges for management. As many have noted (c.f. Drucker current employment policies and management practices may not be 1985) adequate to ensure the that orgsmizat ion has appropriate the htxnan resources and management skills necessary to guarantee that new product quickly developed. raised effectiveness A variety ideas can be most 1983), about huraaji the of organizational resource policies (Fcufcrxm, et. al., techniques (Frohman, 1978) Recently, a nmber of in of concerns have been structure (Kanter, 1984), and managenKnt enhancing product development. strategies have been proposed to identify and enhance factors contributing to innovation and product develojinent in organizations authors have (Burgelman & Sayles, 1986; Drucker, 1985). described how the product development Since many process can be influenced by organizational variables (e.g. Baldridge & Burnham, 1976; Cohen & Mowery, 1984; Damanpour & Evan, 1984), it is not our intent to review or describe sunxnarize of management set a findings. these Rather, issues it facing is our intent to specific groups the responsible for product development within an organization. Within many industries, developnent is the new product names, is the group of this primary mechanism for product the Although known by a variety of team- individuals who oust cooperate to develop, design, test market, and prepare the new product for production. These new product teams differ from many other organizational groups in that they are functional, cross ccnposition across time. face variety a of outside the internally, viable product management The organization, and use of conplex those interactions process inputs (Burgelman, such groups and change in Successful new product teams nust be able to effectively obtain information and resources and tasks, to within such both and inside resources and gain acceptance create of more be infontiation Understanding 1983). caji the frczn others, the operation practical than of groups and between a and usefulness. the product team and other groups within the orgimizat ion can provide a powerful test of general izabi The basic 1 i ty of traditional premise this of research on group processes. paper is that group processes, particularly those dealing with boundary management, can influence the success of new product teams. used to collect data, we wi team nust conplete. Following a discussion of the methods we 1 1 Second, first describe we will the discuss task the new product previous research on boundary spanning, relate this research to the new product team's task, and propose performance. seme relationships between boundary management and team Method The findings this of paper were derived both from a review of literature and frcm over 135 hours of interviews with new product team managers and naembers integrated circuit corporations seven at Four industries. computer the in team leaders were and interviewed within six weeks of conpletion or their projects for between three to Using a semi-structured interview, we asked these managers ten hours. how their new product teams were time (e.g. key events, crises, set how the up, teams evolved over tasks), how the teams coordinated their efforts with other groups, and how key decisions were made. descriptive inportant ninijer of data were factors conqjiled, them what asked success of a new product for interviews other we were conducted. team. they In Another Once these saw as addition, a team leader was interviewed every four to six weeks over a 20 month period to provide some sense develops. of the potential In addition, issues facing a product four managers of multiple teams, 16 team as it new product team leaders and six marbers of teams were interviewed during various phases of development product evaluation of team activities. transcribed; to to The get further a description and interviews were tape recorded and the transcriptions were then evaluated by nultiple raters identify transitions in the product development process and boundary behaviors. This san^jle test is not meant specific hypotheses. adequately represent the Rather, loosely be frcm the described as representative or our goal task and processes This will allow us to augment with observations to be a the current field. to of the ensure that we can new product team. literature on group process Hence, ccnparative is large enough to case the approach we used could analysis. This research strategy was process orgzmizat ions in lack the because we believe chosen formal of we organizations, is an early at research on believe the research and interdependent attanpting group on development. stage of Given groups exploration and that classification of phencrnena, that within description, identify observable to patterns of activities niist all proceed the proposition and testing of specific hypotheses (Gladstein & Quinn, 1985). Tbe Nev Product Team' s Task Recently, Goodnmn has presented a strong argixnent (1986) for the necessity of understanding the task of a group as an integral part any model of group performance likely (Herold, a clear incorrect generalizations about group imderstanding of a group's task, behavior are Without group process. or Therefore, before discussing the 1979). group processes within new product teams, it important to begin with is an understsmding of what the teams must do. A new product team the development product aind Flesher interdependent, are individuals introduction (Flesher, line individuals who are responsible for is a set of of & Skelly, see outside products In 1984). themselves as a the existing general, group, and these are viewed by others in the organization as a group (Alderfer, 1976), even though group men±)ership may change and increase over time. A nixcber of new product groups may be created and aborted early in the developnent process. Those groups survive have potential access to large resources and may shape the future of the organization organizational (Kidder, that 1981). The key to the success of task denands at each phase of these groups the product 4 is to meet the separate development process. This the group be able to effectively obtain requires that information and resources frcm external sources, process the infotrmtion and resources internally, viable product has those inputs (Burgelnan, 1983). and use create and gain acceptance of a to Research on new product managonent identified six phases of new product developnent and new product introduction assiming that Allen &Hanulton, 1982). 1) product strategy is in place (Booz, These six phases include: generation Idea new product a development. This . phase involves It the is initial recognition the step of in new technical a opportunity to fill a perceived need in the marketplace (Holt, 1975). 2) Screening and developnent evaluation The . second phase of product involves the selection of those ideas that deserve further A major intent in-depth study. of this stage is to eliminate ideas not fitting the organization's market or technical strengths (Booz, Allen & Hamilton, 1982). 3) product products Business analysis This phase . consideration under (Mclntyre & Statman, fits 1982) involves determining how the into the portfolio of and whether it is other new economical ly feasible. 4) Deve opment 1 . The development phase centers on the modification of the product idea into a technically feasible prototype. This is the phase in which the group does the bulk of the work designing and building the initial product models. 5) Testing meeting both 1977). This . Testing insures that the new product technical phase and market goals requires monitoring data (Adler, 1966). 5 or standards customer is capable of (Von Hippie, complaints and test . Connercialization 6) The final phase involves the developoKnt . of the production and narketing capabilities necessary to introduce the product on a including the development of mechaniais large scale, for continuing follow-up and monitoring (Booz, Allen & Hamilton, 1982). Each phase describes a sequence of events that a product laist neve through in order to be introduced effectively. process that is activities the and focus One of a iiqp 1 i ca t i on of this new product team nny change over the course of product developnent Although activity, 1978). seme of set reality in Like proceeds this phases process the suggests not is (Quinn, As information Our 1982). interviews decision making process, As developnent product a greater continues, level fed available to addition, corrmercia help in 1 i for process so the order zat ion responsible in there deciding whether to costs develop need to into the ongoing is achieved. group actually may cycle back the screening and evaluation stage, (Frohnan, suggested that specificity of through earlier phases or ahead to future phases. the of only slowly becomes auid collected and is sequence straightforward so often the original product idea is very general more specific. linear new product development often strategic decisions, incrementally a is to an often a rough prototype choose that accurate estimated. be For example, during product. business Those In plan, actually ccmnercial izat ion need to be notified early enough in that manufacturing facilities group waits until the testing phase may well be late to market. It is are available. If the finished to do this, the product has been shown that there is a need to integrate technical and economic considerations early, or large suns of money cem be wasted on a product that 6 is technically feasible but not conmercially viable (Mansfield & Wagner, going times, through several nizoerous functional groups through The process may cycle 1972). hierarchical several levels and (Burgelman, 1983). Product developnent appears to be a messy, undirected process, and indeed, However, suggests. and direct to straightforward less is it two transition points, events as serve events new product the divide inq)ortance indicated the group's each that of sequential shape they Our data suggest process group's segments these three into the phase model define or divide to that in understanding in the the process We refer to these team's activities. demands placed on the group. points than and that change task these trajisition general process, the segments. our placed different Of interviews internal and external demands upon the team. The first of these transition points generally seems to occur just prior to the major portion of the developnent phase and it shift frcm a "possible" project to a "definite" project. shift the comiitment cost this time, product. it is one to and the group giving in is not return the case, for structure itself potential to major capital response to (Pessimier, fairly clear 1977). specification of By the the group cannot be clear about what the support, product. internally, schedules will not be in place. feasibility from low organizational for During this This entails movement from top management should have a over- or under-expectat ions cannot idea. organizational ccrnnitment If this recognition of new product with minimal effort investment frcm a team moves involves the which can In addition, because lead to the group specific goals and The second transition usually occurs sccoe^ere during the testing problens technological The phase. several months working under The upon date. prototype a The team may very will have spent the last exists and has been tested. agreed assessed, been have intense pressure trying to finish at the transition consists of moving team frooa ownership of the product to more general organizational ownership. other time this organizational groups are preparing production and distribution of the product. for large-scale This corresponds to Quinn and Niieller (1972) would call a technology transfer point, moves emphasis the group is organization. the in either unwilling to The transition will relinquish continue to work on the product when to ^ere passing it the be met not the or unwilling to into the hands of product has passed if As one of the managers in our sanple described it, "...then we others. had technology the ixiiat enthusiasn and authority to use that technology to other information, groups from developing At this repairs big fight. later, but \fcnufacturing wanted engineering wanted to to hold build it. now and make it People were very Manufacturing yanked its people off the team." Later, however, "Now we're helping to train the manufacturing people. The group isn't upset. meeting much though, and people don't sean to know what to do now that the intensity is over." These two transition points seemed to divide developiKnt process into three segments (See Figure 1). the new product These segments could loosely be labeled creation, developnent and transfer. In order to understand the developnent of group processes within the new product team, it is necessary to understand the changing task demands over the course of product developnent. As the demands placed upon the product 8 team change across the se^nents of the product development process, we predict that the management of boundary processes and ccnmitment to the product within the team oust change. New Product TtmuB Boundairy Ikfcnaganent in Research on boundary management to date has focused primarily on the organizational and individual organizational levels of analysis. Research at the level has addressed processes by which the organization adapts to its environment by selecting, information 1977; Child, originating the in Individual 1972). tranani tt ing, and interpreting environnent Aldrich & Herker, research has concentrated on the level characteristics of boundary spanners (e.g. (e.g. Caldwell & O'Reilly, 1982) and the role conflict these individuals experience (Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, & Rosenthal, Snoek, Keller & Holland, 1964; 1975; Organ & Greene, 1974). Fewer studies of boundary management have been done at This level. is surprising, because groups, like the group organizations, are open systems that need to manage their relationships with the external environment. the However, much of the research on groups has been done in laboratory or with T-groups groups, the external they exist. to obtain inputs and outputs. consists of work in isolation. For enviroment consists of the organization Groups mist resources, that interact with interdependent others to coordinate work, For carrying same groups, out make decisions, "real" in ^ich in order and exchange this boundary spanning process transactions across the organization- environment boimdary, as well (Thcn^json, 1967). One set of boundary spanning studies that has focused on the group level examines the pattern of work-related 9 information flow in R & D (e.g., Allen, laboratories general, 1984; Katz, 1982; Tusbmn, 1977, 1979). found a relationship between the these studies have information by boundary spanners and performance exanple, R&D high-performing project comnunication with organizational followed a the In showed outside far the addition, information fran outside and then translating the to the group (Tuslman, it research group-level of For greater group than conmuni cat ion first getting information amd Although most of 1979). spanning boundary on input group. two-step process, with conmmication "stars" transmitting the colleagues 1984). (Allen, teams low-performing groups the in In has been limited to studying how menbers bring information into the group, exchange theory would suggest that when a team is part relationships, of of boxmdary spanning needed (Bagozzi, 1975). is system organized by an broader interconnecting web a a conceptualization of Boandary Muaaganesit Decisions Our interviews suggested that, within new product teams, a ninljer of decisions made by team leaders or others in positions of authority could influence the nature of the interactions the team developed with other groups. Thus, the boundary of design variable whereby the the group could be decisions made could determine, the nature of the relations the new product The nature of the 2) part, in team had with other groups These decisions fell into: within or outside the organization. definition of the boundary; treated as a 1) The The permeability of the boundary; and transactions across the group's boundaries. 3) The literature on groups has also addressed these boimdary properties. Boundary Definition. An important tool for defining the nature of the interactions of the team with other groups involves the decision of 10 who is included Including team. the in representatives fron all groups, with whom the team nust deal, on the team is likely to lead to processes boundary different than represented. Similarly, to define resources which the the acquired be inplications externally. the for ^o the decision of nature (O'Reilly & Caldwell, 1986) not team possesses and those which nust the of are on the team will serve is variability of The groups relevant if and group's the team also has internal interactions effectiveness its innovating in (O'Reilly & Flatt, 1986). Boundary Permeability ^ich A second design . the boundary is open or closed. potentially and more cohesive less groups with more rigid which the boundary is boundaries tool is the extent Groups with open boundaries are difficult (Alder fer, control to 1976). open or closed also can The influence (Gladstein, extent the makes transactions across categorized by what is patterns of exchange. influence i ts and Exchanges boimdar ies. exchanged between it nust can units as well social as be the Hence, boundary activity can be categorized by power flow Tichy & Fombrun, information and liking, into whether group meniers or outsiders 1983; way the Choices are also made about the way a team . Aether goods and services, affect and Wood, to 1986). Boundary Transactions and/or those than group views its environment and defines the problems with which deal to out or initiate 1979). of the This the group, exchange broader ideas, and by (Brinberg & categorization describes the set of activities needed to engage in social and economic exchanges necessary to accoriplish interdependent tasks in environoKnts in which resources are somewhat limited 11 or dispersed throughout the organization. this categorization takes In addition, into account not only the hoiindary activities that the group needs to initiate but also the reactive role that group modsers nust play in response to external demands or requests. V^ile group composition least the in short permeability and by influenced often defined by the organization, at hence and ren, nature the behaviors the is the of of the initially boundary fixed, boundary transactions can be group meniers. interviews Our indicate that particular roles are often taken on by group menbers to carry out transactions and change boundary penneabi 1 ity. BoondAry Koles in Hev Prodnct Teana As we previously noted, exchange theory would suggest that transactions across a boiindary could be described by whether the flow was in to or out of the target group and by whether the transaction was initiated within interviews boundary the supported spanning group this roles. conceptualization and suggest One role, which we or resources from other groups and attaint This organizations. is traditional the conception The second role, which we information spanning the Arbassador label role, them back into the boundary of separate Scout seek out to bring from our four term the those activities whereby group merrbers describes group. The data from outside. or in role, describes the activities tsJten by group meniers to transnit information or outputs carry on represent from the group to outsiders. critical boundary group members third role represents inputs from outsiders. Thus, transactions. responses to the scout and aniiassador The requests remaining roles from outsiders. The two things done by the group members in response to We describe this as the Sentry role. 12 The final activities of set the group mprrtiers represent processing of requests for information or outputs frcm outsiders and is termed the Gviard role. The sentry jmd guard rules help to define the permeability of the group Figure boundary. 2 illustrates these roles. This conceptualization of boundary activities discussed those to for He mentions (1980). acquisition organizational five classes organizational of boundary inputs spanners activities: of and by Adams transacting disposal the similar some^vhat is of the outputs, filtering inputs and outputs, searching for and collecting information, representing the organization and buffering At pressure. fluid than the group level, it frcm external threat and these activities are likely to be more described by Adams. In a group, as opposed to organizational boundary imit (e.g., admissions offices, etc.), there an is likely to be a more diverse set of external environments with which to interact, a more general task and fewer formal procedures governing the criteria that Also, the These factors determine when to accept group must manage suggest that or reject within interactions boundary inputs spanning the in and outputs. organization. groups is less bureaucrat i zed than in organizations and that the group nust set rules as it goes along or give the boundary spanner more leeway in making decisions. Given the nature of the new product team's task and the dependence of such groups on others within the organization, should be inportant elements of the team's process. this was supported by our interviews. All of boimdary activities Not surprisingly, our interviewees discussed the iniportance of managing relationships with other groups as critical to the product developnent 13 process. Further, the boundary activities described interviewees the In distinctions described above. the fit with well sections which the theoretical follow, we will draw from the interviews to nsre fully illustrate the roles. Scout We described activities involving bringing infommtion or . resources needed by the group in across the boundary as the Scout role. Exanples task-relevant data supports demand of information information who about extent kind of the of for necessary opposes or the group's the scout might for problan solution, the group's the scout procures other resources, information, training necessary for group functioning, given easily is it ^en the scout who must gather team can negotiate to procure them. well as include political activities, As outputs. collect and the collecting such as equipnent and these resources are not intelligence so that the Exanples of the scout role can be seen in the following remarks made by interviewees: "I came back to the group once meeting...! got the news and went 'letters from heme'.* would go around to the other There was a great deal of and this way I could meike sure well enough in advance so that "I on. on t ime per back week to for a staff my team with groups to see what was going coordination to take care of that coiponents were ordered we could get the product out " . She's very sensitive and works "We have a kind of detector. She with the people interfaces not the technical part. spends time with all the groups in manufacturing to detect problems so they can be dealt with quickly." Ainbassador. The aol^assador role involves representing the groups to outsiders and carrying information, the group chooses to transmit representation the group is (Asians, resources, or other outputs that to others. to shape the beliefs and 1976, 1980). Much of the purpose of this behaviors of others, outside The anisassador develops and maintains 14 channels of ccomin i ca t i on in order to explain the group's activities to powerful outsiders and persuade to outsiders these activities are valuable and should be supported. that the group's These functions n»y involve getting others to comnit themselves to, or share the goals of, the group (Kanter, Kotter, 1983; 1982). The following quotations illustrate the aniiassador role: "After a few weeks we had a design review with all of R & D. We just wanted to make sure that we weren't going off in crazy directions." "Then we started having meetings with all those people outside the group. There were representatives from purchasing, manufacturing, production planning, the diagnostics group, marketing, everyone. This was an opportunity to give information and hear about new business. Everyone was informed about progress and changes. The minutes were typed on line so that the team and those who weren't at the meeting knew what was going on. The top management group also got copies." down where the project first hits and tell 'em I down. say that four things are coming, and this is the most critical. You can't always say rush, rush, I rush. stop in even when there's nothing urgent, to develop a relationship with those people. I send them minutes of our meetings and when the project gets closer I send them memos explaining what's required and asking what they need fron us." "I go to ^at's ccming "I'm like a cheerleader, trying to get those guys excited But I tickle our group too; I'm not about our products. going to carry over some half-baked ideas. They'd get tired of that real quickly." Sent ry . The sentry polices information and resources group. external agents want controlling to send into the the Acting as a filter, the sentry decides who can give input, how nuch of that stop. that boundary by the The input will be admitted, sentry protects minimal distraction. priorities, interests, the and when the flow of group by allowing to it input mist work with Often external entities try to ccramnicate their and daoands. 15 When this input is desired, the " inputs are not desired, 1967). (e.g., Thcxx^son, tensions, political buffering the is for on behalf An extreme group. the of group with the optimal the Lrnprove decision and the group to buffer is The sentry absorbs external pressures, such as that the to be amount of For exanple, effective decision making. 1983) the sentry job of This buffering or sentry function that when action needs not the information and other form of to actually separate the group physically fron the rest of organization. providing V?hen this to allow entry. the sentry is job of evidence information of O'Reilly, 1985; outweigh can indicates information do levels of making (c.f., Gladstein & Quinn, costs in infonnation necessary seme increased taken important is benefits. its Exanples of the sentry role are expressed as follows: "We needed to get input from engineering at the beginning. We didn't want to ccme up with seme kind of Dr. Seuss machine that had to be redesigned later so we let the engineering people in." I the end I talked to the top management group a lot. tried to protect the group from that kind of pressure though. It's like Tom West said, we won't pass on the garbage and the "T^ear pol i tics. External entities may be curious about group activities or Guard. attenyt role ' involves monitoring request information the to those danands. judgment to determine infonration out equipnent of and be the if group. denied, is in Ctae the is external agent request others release in reactive and group's best while another's that the group will The guard role it resources and from the group and determining what response The guard infommtion from the group. resources or to obtain interest requires to may request is let some granted because that group has provided sonething more valuable to the group in return. Examples of the guard role can be seen in the following: 16 "So we set up living quarters axid moved the team away. That People kept coming kind of intensity needed to be isolated. Mhat are you up to now?' over and saying, How's it going? This was at best distracting, at worst like being in a pressure cooker.* "Near the end people started panicking. The top guys would I come down and want to know if we were making progress. told them they had to stop, that they were having a distracting and deleterious effect on the group.'" conceptually and, Both as interviews our inter-related. boundary roles are For support, practice, in example, the scout and sentry roles both deal with information that ccmes into the group. As these both such, world, because inputs external group member influence roles likely to they are perceptions consolidate, filter, thereby distorting than in prone to the "nun" effect the processing of (Zander, of scene outside the and interpret They are also way. 1977) and other selective biases in information (c.f., O'Reilly, Similarly, 1983). the ani^assador and guard roles influence how external entities perceive the These roles define what group. said those outside to four roles represent the said and the manner is Collectively, group. in which the activities it is these serve to define both how the group perceives the external environment and how other actors perceive the group itself. The roles identified elsewhere as organizations. here described coniplement important to the those that been have innovation process Roberts and Fusfeld (1983) argue that gatekeeping, in idea generating, chanpioning, project leading and coaching are necessary for successful innovation. The scout role in our model goes beyond gatekeeping by procuring resources and bringing in political as well as technical detail information. The category to the chanpioning and project scheme we have described adds leading roles by specifying those boundary activities that will aid in recognition of a new product idea 17 , ( chan^ i on i ng and integrating and coordinating the diverse tasks needed ) to develop the product The product champion (project leading). a skilled ani>assador v^ile the project leader nust simultaneously play the role of scout, niist be integrate and often isxbassador, sentry and guard. Finally, our role set stress the team's proactive role in getting and maintaining the support of the coach. In describing boundary management in their new product teams, our interviewees indicated that the various boundary roles can be taken on by one individual or by many different people. As well, a sequence of boimdary activities may contain elements of more than one role. example, the group leader may assine boundary activities all specific person assigned to interact with separate groups. combined, be scouting role or when one is in Similarly, the position of one or a Roles may acnbassador individual may play a may be broadly dispersed, when for exanple, the leader may group menijer each ask that also carried out. is it so For to play the role of guard to keep certain information secret. Boundary Managanent-Perfoxmance Kelatiooships in New Product Teams The success of a new product team can be defined by a product that is delivered on time, on budget, at specification, and that and is a narket success effective and type (Mansfield & Wagner, boundary managenaent of boundary , activity, teams success. is one of to suggest the criticality of boundary spanning roles that 18 the the that amount factors More specifically, we contributing a produced We predict overseeing and controlling spanning new product 1972). is varies across the segments of deve 1 opnen t new product the process. Basically we propse that the scout and airbassador roles are more critical than other boundary roles creation the in of the requires many boundary task process because the segnent product developnent tansactions. During the developnent segment, we would argue that the sentry and guard roles are mare criticla tham the others due to a need to reduce the boundary peiraeabi 1 i The diffusion segment should require proportional ly more ty. atdsassador due activity to increased an need for boundary cross transact ions. In the first predict that the segment of the product developnent process, we would scout other boundary roles. segment creation groups them, who will external their environment, necessary. In are more process In order 1977). top management, addition to technical it and other than during the is effective that oust collect infonoation (Kanter, to develop feasibility, econcmic critical form the group) later technical, emd political 1969; Tushraan, evaluate jmd roles developnent product the of large amounts of market, 1983; Maquis, ambassador Our interviewees suggested that individuals (or and ideas, screen information functional fron the areas is and market based activities, an under stsmding of the corporate tradition and managefoent thinking may be needed to know whether the product might be included in the corporate strategy (Burgelnsin, 1983). role of process, the scout. gaining During Collecting this information represents the se^nent this top management support of and interdependent groups may also be crucial. internal corporate venturing describes demonstrate that what conventional the the product cooperation of other Burgelman, this development as in his study of "...necessary to corporate wisdom had classified as 19 . in^ssible vas, in fact, possible" infommlly obtaining resources early market creating managenKnt This nay require 232). p. dononstrate product to interest product the in feasibility even before or top ccnmitted to the product's develojxnent is When (1983, the primary task of group a gather to is infonoat ion, resources or expertise outside the group, we hypothesize that effective increase those activities related to scouting. groups will resources the group upon what increased scouting activities requires, may be directed toward a variety of outside groups When cooperation from others group's outputs, we predict needed is that in Depending (Pfeffer, future acceptance for effective groups, start early in the group's existence to the 1985). the of scout will identify areas of support and opposition to the team's efforts. At this stage, those activities making up the arrfcassador role are The anliassador uses predicted to be high in effective groups as well. the information from the scout, working to maintain the support those who have given and trying it who oppose the groups 's obtain to whose support plains but it from frcm key individuals needed. Cooperation is and support are built early, emd those who agree to cooperate are kept informed group's outside Once group progress. of output, support need they and to these groups updated be cooperation the antassador beginning of performing performs. the group's teams will This existence. continue to activity, but its form may change. 20 is when Thus, not the in present, we increase the amount of selling particularly inportaiit at Once support need stake progress. necessary but are predict that high performing teams will that on have a a fair is amount obtained, of the high- anl>assador The literature on group behavior would suggest that it is important that this role develop early in the team's existence and data frcm our support interviews Friedlander and Scott contention. this found that work group activities were give naore (1981) legitimization and were more likely to be in^jlemented when there was a back and forth flow of with ideas top management. information channel is established, over time other unrelated purposes are given effective were for the aiil>assadors Descriptions groups. (March & Simon, tends it 1958) work or to be used for once outsiders who that so a information early in the team's developnent may reciprocate assistance with addition, In unlike not worked of those Our team. interviewees build to informal processes the suggested channels they imdertook requirements with other doing in voluntary for that this coordination identified by Whet ten (1983). h3rpothesize other second the In that segment of sentry and the boundary roles. partial isolation of the It is team product the guard the most is process, we are more critical than development segment, when roles during developnent inportant, that the team rtust specify the new product design well enough to set goals and schedules for the agents design team. In regarding need to be radically changes). order their halted This for this to priorities be and (imless market is the sentry done, inputs suggestions or frcm external for coopetitive function. the product information We would predict that the more effective teams will be the ones that are able to get the inputs they need and then to consolidate this to develojinent taking in of . information and move on Groups which are not able to effectively manage this information and then using 21 it may lose valuable time or , suffer Groups reduced effectiveness. continue that incorporate to outside inputs may continually change work goals and schedules so that group manager put to and motivation may progress new product one team "They just couldn't decide which chip they were going it, It use. As suffer. was debated and changed and debated until the cost and We had to scrap the whole thing and nest delivery got out of control. of that team left the company." The sentry mist protect the group from this sort of input overload The team needs to spend by naking the group boundary less permeable. its time on technical development; transfonn the must speed inputs be gained by having can interference external 1984; Galbraith, guard The into at finished a 1982; Rogers, 1982). also buffers the effectively, propose that suggested interviewees Our it cannot the more product. Innovation While team. how much progress has been made, finished. that organizational developnent phase external agents will want doing, this point sentry serve as the inpOsed and is it to know if group important the team's is the in is product will be the team interrupted constantly. be against the group vrtiat the and (Friedlander norms or v^en that buffer a the the group product, is to work Therefore, and we the more interruptions and requests for information and resources, the more the guard role is necessary. In addition, teams will often be in conpetition for resources and will want product information in order to ccfifjete more successfully. will manage We hypothesize that high performing teams their profile and limit guard role. 2Z their exposure to others via the s It that although ne propose to note inportant is that the sentry and guard roles are most important in the second seg^nent of new product developnent the ani>assador and scout , crisis. provide guard and sentry It protection needed the meet to the The second possible that the product will not be pushed ahead to is comnercia 1 zat ion i unless Technical development. roles still are necessary. team the expertise, to complete information about carpeting groups zmd resources and top management support, alone left is in the form of equifment and personnel may also be needed to meet the demands at this second crisis The point. activities scout takes on these continue in order to ccnmitments to the product latter the roles two are while activities, garner the annbassador ' and maintain others' support Nonetheless, we would postulate that idea. required less during this second segment of act ivi ty. In the hypothesize final that boundary roles. convey segment technical is during data as well critical that it in this endeavor. may be necessary ambassador activities. role as is a developoent more transfer the that will manufacture and market is product the aniassador the It of that sense of most ownership other the to the groups The annbassador role tremsition group members The transfer of ownership of may be difficult for the team. than we effective teams mist the new product. The breadth of for critical process, is such to assme some the new product The nature of the second segnent of the developnent process may have caused the team to have developed a very inpermeable boundary. Although the isolation this boundary creates may be inportant in innovation, its existence and the cohesiveness that has 23 developed nay beccme detrimental at We propose that the stage. this potential of this occurring makes the an±)assador role critical. Overall, we hypothesize that the critical ity of the boundary roles change depending upon the product Koroleva particular studied (1984) this hypothesis for Ryssina and institutes. relationship between roles and the slightly different examining Although perfonrance. support research engineering study of required at each phase of tasks General developnent process. fron a cases the teenn their roles, findings support role differentiation and active management of boundary activity. closer their In scientific leader focused and were scout) (like then the teams the contacts, were factors two better associated with cooperation and increased The research indicated that the generator of ideas and effectiveness. gatekeeper these study, primary of inward with in early phases, activity falling on the burden of Finally, specialist. technique research in^rtance the leader, specialist and interface mtmager become most important. Team Kfcnagonent and Fntare Research Iiqplicmtioas for An improved understanding of conplex groups such as new product teams nay have more inportant We have inapl ly, icat ions increasing identified The scout, activities. for inproving the managonent of teams and said improving research on groups. four roles which myriad transactions with the external always be taken on automatically. this paper assign is these perfonmnce sentry, aniassador, If to group members in these roles. Role performance 24 boundary the Roles will not support and these and guard acconplish environment. forthcoming, we would suggest roles enccrnpass for that the propositions the evaluate is in team leader niist them on their also influenced by the organizational organizational The context. and reward control team leader must work mechanisms encourage to and make reward effective role behavior. The propositions presented here have in^lications for research as First as managonent. well foremost and the paper teams within their organizational context recognition groups that Also inherent processes. internal as well as levels This broad perspective lines. in in is the propositions time and is their the hierarchy and across needed to understand nx>re that may be necessary to meet of the group behaviors studying to examine boundary should be monitored over interactions monitored both across functional in order advocates the task demands of ccrplex interdependent tasks like new product developnent. Much of the current literature on group functioning suggests that team leaders spend their time fostering good internal group processes such as effective decision making and problem solving, support iveness and 1977). trust, Argyris, (e.g., these processes are clearly 1966; Dyer, iitportant in outlines other areas of group process. leaders the of all groups that are 1977; Zander, team managonent, While paper this New product team leaders, and interdependent with external entities, must successful ly manage a conplex set of boundary activities as well if N4ich the group is to meet of the current group its goals. literature uses cross sectional data. Those researchers who have taken a developnental approach have focused on the will 1973). resolution of leadership two major emerge and issues: authority and how close will we became?) intimacy (c.f. (How Hare, Development has been modeled as a sequetnial process shuch as: 25 develops as group merdjers confron issues of authority; 3) mmi jers agree on nonrs and rules; and 4) work leads to ccmpletion of the task (Heinen & Jacobsen, This 1976). in behavior changes interpersonal internal concentrates development view of seen over groups in on the time. Our findings support the developnental approach but indicate a need to evolution the on focus process raises also research This follow shifts sec[uence. of boundary asa well question the processes. internal whether rather task demands in of as in group than an universal stage changes Future research will have to address this issue. Beyond the identification of boundary roles related to the product the data developiKnt process, inplication an additional about from our interviews lead us to speculate effects of a group's for that research, are what is, the processes on the nature of its boundary internal relat ions. The Interaction of Internal and External Group Processes An area worth seme speculation the group influence transactions two least (c.f. Gladstein, processes were to the the how the permeability of the 1984). processes internal is developnent the processes of internal boundary and boundary Our interviews suggested that at influenced boundary activities. and majiagement of inenfcers' These coranitments team and product and the management of the stream of decisions involved in developing the new product. \fanaging Carmitraent . Our interviews suggested that nanaging the creation, maintenance and control of the project is inportant in shaping the teaiiB both the product team with other groups and the overall development process. The new product 26 members' relations coranitment of the to new success of the product developnent process has many and unforeseen demands and pressures as one manager we interviewed "there isn't one project that hasn't gone through a stage where stated, the morbers thought failed they had — ^ere they thought it couldn't be done.* Despite this, exanples abound of teams expending tronendous effort the in interviewees our apparent face of recounted failure (c.f. Kidder, of marathon stories work 1981). Kfeny of willingly days, forgone vacations, amd intense effort toward the developnent of the new product. It the to 1979) may be, becoming that new product is "fanatically often necessary for conmitted" (Quinn, team success the in face of perceived failure. Conxnitment may be paradoxical ccnmitiQent may be very motivating for team menisers, individuals beconae bound by their previous actions they become comnitted an to unsuccessful in having or "too n»ich entrapping conni tment strategies or ccnmitment lead lead to limit may prevent team to the individuals (Caldwell & O'Reilly, 1984). the new product For comni tment exanqjle, penneable activities a distort to quit" such a way that of (Rubin & Brockner, (Teger, Such 1980). team frcm abandoning poor new information. Similarly, or manipulate information All of these negative outccraes may serve it may have to exchange information with may be dependent. implications exhibiting than necessary. the ignore "fanatically" boundary by to team's ability those other groups upon which Thus, invested may also have This process strategy. escalating ccmni tment has been termed "entrapnent" 1975) it intense 1982) has described how Recent research (c.f. Staw, negative effects. Although however. for boundary behaviors. conmitted group may develop a higher Similarly, 27 levels of sentry and less guard the comni tment may distort the boundary transactions such that the group concentrates on exporting its the the paradox of is Wiile "fanatical" camutment may be necessary to conplete ccrnnitment. a project, This then in^orting new information. views without such ccnmitment may make the existance of group work with to others or it difficult ultimately give to over for the "ownership" of the project to others. Increasing amounts of research have identified how the processes by which individuals undertaJ^e an action may lead to coranitment (c.f. O'Reilly & Caldwell, 1981; Salancik, 1977) and how such coranitment may be maintained future research analysis, organizations in is the managanent including its Pfeffer, (c.f. ccnmitment at of implications One area 1981). the group level internal for and for of boundary processes. Managing the Decision Making Process that is likely outside groups to is influence As others have noted group and processes. (c.f. decisions the 1982), makes internal the can influence Our interviewees suggested that the team had the potential by the product interactions with decision making within the team. the Janis, it team's product the nature of the A second internal process . to ^y process of external the group decisions were made influence the way the group managed its boundary. In order management to understand how decision making can new product in understanding of two models rationality. of "why" teams, it is useful decisions are made. decision decision making; influence boundary to Brunsson begin with (1982) an compares rationality and action Decision rationality corresponds to most no rma t ive models of decision making whereby the goal 28 of decision making is to meike the Processes decision. "best" as collecting sets of alternatives, complete specifying information, such and requires avoiding (Janis, 1982) irrational such rigid responses to threat or ranking Making "good" alternatives in terms of expected values are called for. decisions available all processes as group think Sandelands & Dutton, (Staw, 1981). frcm decision rationality in that the Action rationality differs aim may not be but their The done input issue one less should be group effectiveness of and more done) one (Pfeffer & Salancik, building of implies decision making process the in that as so gain to molding the decision and build their comnitment to in is carried out the people involve to the "best" decision in scRie abstract sense, to arrive at cormitment as how the decision of primary criterion will being is best can be Since action rationality has 1978). a few alternatives (whether v^iat it. analyzed, be success, for a this narrow range of potential consequences should be used to choose among the alternatives, and implementation process (Brunsson, decision of all normally avoided because Our interviews pros it 1984). rationality action the throughout dominant Gladstein & Quinn, 1982; rationality, consideration should be issues and cons of In the contrast suggests niiltiple entire that alternatives to the is could evoke dysfunctional imcertainty. that suggest a team operating under decision rationality exhibits a more permeable boundary that one operatin imder action rationality. Those teams using a decision rationality approach displayed an openness for new information. to move outside information on the boundary their pros to generate and cons. 29 Team meni)ers seemed ready new alternatives and obtain Teams operating imder action rationality often wanted to accelerate the decsion oaking process and seoiKd inclined less seek new to inforamtion which might inpede the decsion making process. SmDOBTy First, These conclusions have inplications in two general areas. they suggest products that of function of a is part the success the extent in effectively developing new the product develojment to which team is able to manage its relationships with other groups. internal Second, this activities and research. Whereas maintenence functioning: processes may have relationship needs group activities, has research our work boundary management. 30 to an impact be examined typically suggest a looked third on at area boundary in future task of and group I 1 3 iK s S6 a. s f * • BEFERENOES "The Structure and Dynamics of Behavior in Organizational AdaoB, J.S. Handbook of Industrial In M-D. Dunnette (ed.). Boundary Roles." and Organizational Psychology ." Chicago: RandMd^ally, 1976. Adams, J.S. "Interorganizat ional Processes and Organization Boundary 2 (1980): Activities." In Research in Organizational Behavior 321-355. , "Time Lag in New Product Adler, L. Market ing January 1966, 17-21. Development." Journal of , In "Boimdary Relations and Organizational Diagnosis." Behavior Edited by M. pp. 109-133. Springfield, IL: Charles Thonas, 1976. Alderfer, C.P. Hxinanizing Organizational Meltzer and F.R. Wickert. , "Boimdary Spaiming Roles and Organization Aldrich, H. and Herker, D. 217-230. In Academy of Management Review 2 (1977): Structure." Technology Transfer and Allen, T.J. Managing the Flow of Technology; the Di ssgninat ion of Technological Information Within the Cambridge, M\: The M.I.T. Press, 1984. Organization R&D . Harvard "Interpersonal Barriers to Decision Making." C. 84-97. Business Review 44 (1966): Argyris, "Marketing as Exchange." Bagozzi, R.P. No. 4, (October 1975): 32-39. Journal of Marketing , Vol. 39, Organizational innovation: Individual, Baldridge, J. & Burnham, R. organizational, and environmental inpacts. Administrative Science Quarterly 1975, 20, 165-176. , Booz, "New Products Inc. 1982. In Business Engineering Allen and Hamilton, 1980s." Msmagement for the , "A Resource Exchange Theory Analysis of Brinberg, D. and Wood, R. Consimer Behavior." Journal of Consimer Research Vol. 10, No. 3, 330-338. (Deceifcer 1983): , "The irrationality of action and action Brunsson, N. Decisions, ideologies and organization actions." Management Studies 1982, 29-44. rationality: Journal of , "A Process Model of Internal Corporate Venturing in Burgelman, R.A. In Administrative Science Quarterly the Diversified Major Firm." , 1983. Strategy, Inside Corporate Innovation: Burgelman, R. & Sayles, L. Structure, and Manager ial Skills. New York: Free Press, 1986. 31 t "Boundary Spanning and Individual D. & O'Reilly, C. Journal of Applied The Impact of Self Monitoring.* Performance: Psychology 1982, 67, 124-127. Caldwell, , "Responses to Failure: Caldwell, D. & O'Reilly, C. The Effects and Choice and Responsibility on Impression N^nagement." Academy of Management Journal 1982, 25, 121-136. , Child, J. "Organizational Structure, Environment, and Perfonnance: The Role of Strategic Choice." Sociology 1972, 6, 1-22. , Cohen, W. & Mowery, D. Firm heterogeneity and R&D: An agenda for research. In Barry Bozeman, Michael Crow and Albert Link (eds.) Strategic Management of Industrial R&D Lexington, MA: Lexington, 1984. . F. & Evan, W. Orgamizat ional innovation and performance: The problem of "organizational lag." Administrative Science Quarterly 1984, 24, 342-409. Damenpour, , David, E. Trends in B&D. Drucker, P. The discipline of innovation. , June, 1984. Harvard Business Review , 1985, 67-72. Nfey-June, Dyer, Research and Deve 1 opnen W.G. Team Building; Issues and Alternatives Add i son-Wesley Publishing Qnpany, 1977. . Reading, M\.: Flesher, D.L. Dec i s i on Flesher, T.K. and Skelly, G.U. The New-Product New York, NY: National Association of Accountants and Hamilton, Ontario: The Society of Management Accountants of . Canada, 1984. F. "The Ecology of Work Groups," to be published in The Handbook of Organizational Behavior Jay Lorsch, General Editor, Prentice-Hall, 1984. Friedljuider , . Friedlander, F. and Scott, B. "The Use of Work Groups for Organizational Change." In Groups at Work , ed. C. Cooper and R. Payne (New York: Wiley, 1981). Frohman, A.L. "The Performance of Innovation: Nknagerial Roles." 5-12. California Management Review Vol. XX, No. 3 (Spring 1978): Fombrum, C. Tichy, N. Nfanagement New York: , , Galbraith, J. Dynamics , Devana M. Strategic John Wiley, 1984. Human Resource , "Designing and Innovating Organization." , 1982, 16, Organ izat ional 5-26. Gladstein, D, "Groups in Context: A Model of Task Effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly 1984, 29, 499-517. , 32 Group " Gladstein, D. "Adaption to the External Environment; Group Developnent in the Organizational Context." Working Paper, Sloan School, M.I.T., 1986. Gladstein, D. and Quinn, Decision Making." Decision Making . J.B. "Janis Sources of Error in Strategic To appear in H. Pennings (ed.) Strategic San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1985. Goodman, P. Task, technology and group performance. In P. (ed.) Designing Effective Work Groups . San Francisco: Bass, 1986. Hare, Paul A. "Theories Interaction Analysis." Z59-303, August 1973. of Group Development Small Group Behavior . Goodman Jossey- zmd Categories for Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. Heinen, J. Stephen and Jacobson, Eugene. "A Model of Task Group Development in Complex Organizations and a Strategy of Inplementat ion. Academy of Management Review October 1976, pp. , 98-111. Herold, D. The effectiveness of work groups. Orgzinizat ional Behavior . Colxrrbus, Ohio: Grid, Holt. Kerr In S. 1979. "Information and Needs Analysis in Idea Generation." Managengnt 1975, 18, 24-27. (ed.) Research , Janis, Grroupthink (2nd edition). I. Boston: Houghton^vlif f 1 in, 1982. Kahn, R.L. Wolfe, D.M. Quinn, R.P. Snoek, J.D. and Rosenthal, R.A. Organizational Stress: Studies in Role Conflict and An±)iguity . New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1964. ; Kanter, R.M. , ; ; The Changemasters (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983). Katz, R. "The Effects of Group Longevity on Project Comuunicat ion andd Performance." Administrative Science Quarterly (1982) 81-104. "Boundary Spanning Roles in a Research and Keller, R. and Holland, W. An Enyirical Investigation." Development Organization: Academy of Management Journal 1975, 18, 388-313. , Kidder, T. The Soul of a New Machine . Little Brown eind Kotter, Ccmpsuij, J. "What Effective General Managers Really Do." Business Review 1982, 60, 156-167. 1981. Harvard , "Organizational and Strategic Factors E. and Wagner, S. Associated with Probabilities of Success in Industrial R&D." In The Journal of Business 179-198. (1972): Ivfensfield, , Maquis, D.G. "A Project Team Plus PERT Equals Success. In Innovation 1, 3, (July, 1969). , 33 Or Does It?" N4arch, J.G. and Simon, H.A. Martin, J. & Siehl, C. uneasy s^rabiosis. Organ izat ions . New York: Wiley, 1958. Organizational culture and counterculture: An Organizational Dynamics Autimn, 1983, 52-64. , Mclntyre, S.H. & Statman, M. "Managing the Risk of New Product Development." In Business Horizons (May-June, 1982): 51-55. , O'Reilly, C. "The Use of Information in Organization Decision Making: and Some Propositions." In L. Cuimings and B. Staw (eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior (Vol. 5), Greenwich, Conn: JAL Press, 1983. A Model , O'Reilly, C. & Caldwell, D. The ccranitment jmd job tenure of new en^jloyees: Scrae evidence of post-deci s i onal justification. Administrative Science Quarterly 1981, 26, 597-616. , O'Reilly, C. & Caldwell, D. "Work Group Dei»graphy, Social Integration, and Turnover . " Working Paper, School of University of California, Berkeley, 1986. Business, O'Reilly, C. &Flatt, S. "Execut ive Team Demography, Organizational Innovation, and Firm Per formeince. " Working Paper, School of Business, University of California, Berkeley, 1986. Organ, D. and Greene, C. "Role Arcbiguity, Locus of Control and Work Satisfaction." Journal of Applied Psychology 1974, 59, 101-102. , Pessemier, Product Management; John Wiley, 1977. Strategy and Organization . New York: Pfeffer, J. A resource dependence perspective on intercorporate relations. In M. Mizruchi & M. Schwartz (eds.) Structural Analysis of Business New York: Academic Press, 1985. . Pfeffer, J. Management as symbolic action: maintenance of organizational paradigms. In (eds.) Research in Organizational Conn: JAI Press, 1981. creation and The L. Cumnings & B. Staw Behavior (Vol. 3) Greenwich, Pfeffer, J. & Sa l ancik^ G. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective New York: Harper & Row, 1978. . Quinn, J.B. Technical innovation, ent repreneurship Sloan Management Review , Spring, 1979. Quinn, J.B. "Managing Strategies Incrementally." and Qmga strategy. (1982): 613- 627. Quinn, J.B. & Mueller, J. A. "Transferring Research Results to Operations." In Harvard Business Review (January-February, 1963): 49-87. 34 Roberts, E.B. and Fusfeld, A.R. "Staffing the Innovative TechnologyBased Organization." CHEMTECH; The Innovators' Magazine (\fay 1983): 266-274. Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations Gxipany, Inc., 1982. Rubin, New York: . Kfedvlillan Publishing & Brckner, J. Factors affecting entrapnent in vsaiting The rosencrantz and guildenstern effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1975, 31, 1054-1063. J. situations: , Ryssina, V.N. and Koroleva, G.N. "Role Structures and Creative Potential of Working Teams." R&D Nfanagement 14, 4, 1984, 233-237. Salancik, G. Ccmnitment and the control of organizational behavior and In Barry Staw and Gerald Salancik (eds.) belief. New Direct ions in Organizational Behavior Chicago: St. Clair, 1977. . Counter forces to change: 6. Escalation and ccxnnitment as In P. Goodman (Ed.) sources of administrative inflexibility. ChaJige in Organizations San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1982. Staw, . B. Sandelands, L. & Dutton J. Threat-rigidity effects in organizational behavior: Anulti-level analysis. AAninistrat ive Science Quarterly 1981, 26, 501-524. Staw, , , Teger, A. Thcn^json, Too Much Invested to Quit , 1 New York: In Action Organizations J. Coipany . . Pergamon Press, 1980. New York: McGraw-Hill Book 967. Tichy, N. and Settings." Fombrun, "Network Analysis C. Huian Relations , Vol. 32, No. 11, in Organizational (1979): 923-966. M. "Special Boundary Roles in the Innovation Process." AAninistrative Science Quarterly 22 (1977): 587-605. Tushman , "Work Characteristics and Solounit Comnunica t on Tushman, M. Structure: A Contingency Analysis." AAninistrat ive Science Quarterly 24 (1979): 82-98. i Von Hippel, E.A. "Has a Custcxner Already Developed Your Next Product"? 63-74. In Sloan Management Review (Winter, 1977): ^etten, D. "Interorg2mizat ional Relations." To appear in Handbook of Organizational Behavior Jay Lorsch (Ed.), Prentice-Hall, 1983. , Zander, A. Groups At Work Publishers. . San Francisco, 1977. k253 087v.^ 35 CA: Jossey-Bass H : R^^£tfl£^l)n. ^UQ 16 IHM 1991 ^5^99^ Lib-26-67 TOflD ODM 53D 2Mt.