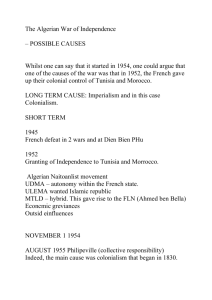

THE POLITICAL CONTEXT BEHIND SUCCESSFUL REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTS, THREE CASE STUDIES:

advertisement