Visit our website for other free publication downloads U.S. FOREIGN POLICY

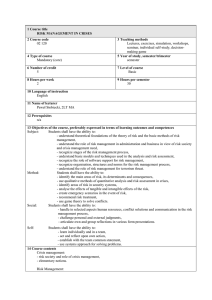

advertisement