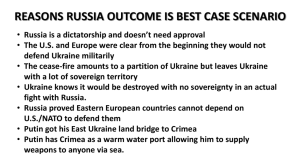

POLITICAL TRENDS IN THE NEW EASTERN EUROPE: UKRAINE AND BELARUS

advertisement