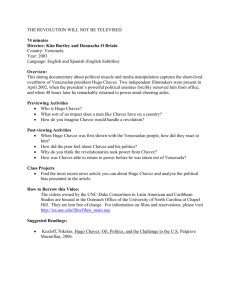

LATIN AMERICA’S NEW SECURITY REALITY: IRREGULAR ASYMMETRIC CONFLICT AND HUGO CHAVEZ

advertisement