Document 11045802

advertisement

HD28

Dewey

.M414

oo.

Ifcol

ALFRED

P.

WORKING PAPER

SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT

GENERIC STRATEGY AND THE PRODUCT LIFE CYCLE

by

MING-JE TANG

August 1984

1601-84

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

50 MEMORIAL DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139

GENERIC STRATEGY AND THE PRODUCT LIFE CYCLE

by

MING-JE TANG

August 198A

1601-84

SeP 2 4

'

1

r iii r iii

1985

The product life cycle(PLC) concept has been widely discussed in business

literature since

was

it

introduced by Forrester in 1959.

first

usually advanced in the contexts of new

allocation as

aid

an

to

strategy

formulation

business unit(SBU) level and the corporate

is utilized

that the

PLC

PLC is a

good

competition

indication

in

resource

both the strategic

at

level.

and

is

primary

The

reason

strategic planning is that the stage of the

trend

the

of

However,

pattern.

planning

product

It

primary

in

proposition

this

demand

has

and

the

been

not

substantiated or refuted empirically.

Taking one step further, there are

three sequential questions that

to

utilize the PLC concept:

what are

(i)

need

answered

be

Is the concept valid?

before

(ii)

If

the characteristics of each stage of the cycle?

characteristics are correct, what are

these questions

If

those

Answers

been sought in the published literature.

have

can

is valid,

it

(iii)

implications?

their

one

to

The PIMS

data base will be used to empirically test various propositions regarding

the three questions posed above.

This analysis places emphasis on the effects of the PLC

strategies of

Generic

SBUs.

strategy may be defined as the most basic

decision made by an SBU in the hierarchy of its

paper seeks

to

identify

generic

the

on

generic

strategies

decision

in

identify appropriate generic strategies for SBUs in

the

This

making.

industry

separate

and to

stages

of

the PLC.

This paper is organized into five sections.

the basic

concepts

of

The first

section

presents

the PLC and the empirical evidence related to its

Since the empirical studies of the PLC almost exclusively deal

validity.

with the validation of the shape of the PLC, an attempt has been made

PIMS

use the

data

base

to

different stages of the PLC.

further explore the characteristics of the

presented

The results are

The third section attempts to develop

section.

generic strategies

the industry.

in

to

a

the

in

second

methodology to identify

This methodology is applied to the

chemical industry and the machinery industry.

Utilizing the

results

of

third section, the fourth section studies the generic strategies

the the

of SBUs in different

stages of the PLC.

The final section

examines

the

effects of the length of the PLC on an SBU's generic strategies.

I

The Product Life Cycle

The primary focus of the PLC studies is the shape of the PLC.

the PLC is determined,

shape of

which

in

it

discuss

a

the

can be used to forecast future demand

turn, constitutes a base for strategic planning.

will first

Once

This

section

theoretical model of the shape of the PLC and then

present a literature review of the empirical studies of the PLC.

1.

A Theoretical Model of the PLC.

The PLC represents the unit sales or unit demand curve of a product

time.

Usually,

the

PLC

divided into four stages:

The only

rationale

is

approximated

by

over

an S-shaped curve and is

introduction, growth, maturity,

and

decline.

underlying the shape of the PLC that can be found

the literature is the theory of innovation diffusion. [Bass ,1969]

in

The innovation diffusion process is usually viewed as a social

basic premise is that, over time, the information diffuses

The

process.

and the likelihood that the economic agent will adopt the

innovation

is

function of the number of agents that have already adopted

an increasing

it.

contagion

The process can be described by the equation:

dx/dt=ax(l-x)

Where

x

(1)

is the

proportion of adopters to total

the parameter, a,

potential

indicates the "potency of spread."

adopters,

and

The solution of the

above differential equation is an S-shaped curve.

The use of the diffusion theory as the rationale for the shape of the PLC

has attracted three major criticism.

First, it does not cover the replacement

employed to

forecast

total

demand

and

thus

can

not

be

demand, especially for frequently purchased

goods.

Second, the diffusion rate only explains

stages of

the

of substitutes,

PLC.

the

growth

and

the

maturity

The decline of a product is caused by the emergence

which is not included in the innovation diffusion

model.

Third, the demand growth of a new product is the sum of the shift of

demand

curve

and

the

movement

along

a

given

demand

curve.

Chow[1966]and Bass[1979] have pointed out that the diffusion theory

the

Both

only

explains the

shift

the demand curve, but ignores the movement along

of

the demand curve which results from

experience curve effect in

predict the

shape

competitive market.

a

in

a

are

Typically, there

(e.g.

planning.

aggregation

product

level of

at

form

Regal) [Polli and Cook, 1969].

substitutes

that are

Thus, to understand and

if

the PLC is to

used

be

The first step is to determine the

which

the

will

PLC

employed.

be

levels of product aggregation-product class

three

product

automobile),

the

addition to the diffusion rate.

strategic

in

by

price change, the substitute and the

The basic concept of the PLC must be clarified

effectively

caused

the PLC, one has to consider the experience rate,

of

income and substitution effects of

replacement rate,

decline

price

the

(large

and

car),

brand

(Buick

Product classes include all those products

for the same needs.

Ideally, objects belonging in

different product classes should have zero demand cross-elasticities.

product class thus defined can be referred to as an industry.

is not

cycle consists of the life cycles of product forms,

product form and shows

than the

life

pattern.

Moreover, most industries are in the

stay there

cycle

indefinitely

population[Kotler

have close

of

,

1980].

a

since

it

a

is

longer

usually

somewhat more stable

maturity

and

stage

may

their demand is highly correlated to the

The brand level is also inappropriate,

brands

Since

substitutes and their sales show an irregular pattern.

the brand life cycle is too erratic and the industry life

steady, most

This level

Since the industry life

for use in the PLC concept.

appropriate

A

cycle

is

too

marketing researchers agree that product forms are the most

appropriate level of product aggregation

in

utilizing the PLC

concept

The second step and a major criticism of the PLC is the determination

the current stage of the PLC of the products of a business.

it

is

Usually, the

business is in is determined by the demand growth rate.

stage the

difficult to estimate future demand growth,

able to locate itself exactly in anyone stage.

generally know

the

stage

it

is

the

business

is normally distributed with a zero mean,

in the growth stage

if

not

is

observing the market growth rate

in by

assuming that the percentage change of

By

Since

However, the business may

over a period of time and then, using the method suggested by

Cook[1969].

of

a

and

Polli

product's sales

they suggest that a product

is

its percentage change in sales is greater than 0.5

cr;

and is in the decline stage if the percentage change is less than -0.5

C

and

is

the maturity stage if the percentage change is within the

in

range of +0.5 C.

Third, as indicated, the determinants of the shape of

diffusion rate,

the

product substitutes.

technological

substitutes.

experience

the

PLC

are

the

rate{if the market is competitive), and

Promotion may increase the diffusion rate

and

the

emergence

of

Therefore, the shape of the PLC is partially determined

by

policy

of

the

business

may

affect

the

the behavior of the firms in the industry.

In sum,

shape of

the innovation diffusion theory is not sufficient to explain

the

PLC.

The

concept

of

PLC itself lacks accuracy.

necessary then to examine empirical evidence regarding the shape

PLC.

the

It

of

is

the

2.

Empirical Studies of the Shape of the PLC

Research concerning the shape of the PLC covers both industrial goods and

,

Studies

consumer goods.

diffusion

S-shaped

curve

1968, Romeo 1975].

For

quantitative study

of

industrial

of

Kluyver [1977]

example,

the

products.

new

of

goods

usually

validate

[Davies

1979, Mansfield

has

data.

and

,

a

a,b,c,d

and

t,

e

is

the

to

base

of

natural

the

are constants to be estimated from the

f

His study suggested that the components of

heavy-duty

of industrial goods,

and

truck

Except for

farm equipment industries have varying S-shaped sales curves.

the diffusion

data

set of

His formulation is

where St denotes the sales in time

logarithm

typical

a

Kluyver first specified a mathematical

PLC.

formulation of the shape of the PLC and then collected

test his formulation.

done

the

even for educational innovations, the

traditional S-shaped diffusion curve fits very well in five

out

six

of

cases[Lawton and Lawton, 1979].

For consumer goods, however, the classical S-shaped PLC has been

pattern of

Swan{1979)].

the

many

patterns

discovered

by investigators.

a

[Rink and

The major difference between the various patterns found

empirical studies is the behavior of sales in the maturity stage.

in the

major

in

Except

classical S-shaped PLC, the maturity stage may exhibit innovative

maturity [Buzzell 1966, Levitt 1965], or

stable maturity [Buzzell ,1966]

,

cycle-recycle

which are shown in Figure

[Cox

1.

1967],

or

Sales

Sales

Innovative Maturity

Sal^s

Stable Maturity

Cycle-Recycle

Figure 1

Types of the PLC in the Maturity Stage

For the S-shaped sales curve, Bass[l969] deveoped an S-shaped sales model

for new consumer durables based on the diffusion theory.

his

S-shaped

model

fits

sales

the

history

durables(ref rigerators, air conditioners, etc.).

the applications

of

1980].

found

that

consumer

eleven

Nevers [1972]

His results also validate the Bass

in many international settings,

some

He

extended

the Bass model to the retail service, agricultural,

and industrial sectors.

limited, unless

of

.

model.

But

the predictive power of the Bass model is

qualitative

judgments are made[Heller and Hustad,

Other than the Bass model, evidence supporting the S-shaped

PLCs

can also

found

be

nondurables.

Polli

and

[1967],

in a

in

But, Cox

Cook's

study

study[1969]

of

of

140 consumer

ethical-drug

258

brands,

identified six patterns of the PLC and found that the cycle-recycle model

shown above best fits the data for about two-thirds of the drugs studied.

He suggested

the

that

"recycle"

is

due to the heavy promotion by the

producer when sales decline.

His finding suggests that firms'

policy may extend the life of

a

promotion

product.

Another piece of work which does not follow the S-shaped pattern is found

in Buzzell [1966]

continuous

.

rapid

He found that some processed food

growth

(innovative

maturity,

material

[Levitt 1965].

costs.

Nylon

also

exhibited

rapid

year

million

1962

if

its

pounds in 1962 because of the development of new

uses in tires, carpet, gears and sweaters.

fact that companies'

in

Demand

However, demand actually

sales were to follow the traditional PLC model.

approached 500

decline

the same sales pattern

Nylon was used originally in parachutes and rope.

would have peaked at about 50 million pounds per

either

cereal)

e.g.

because of high rates of product innovation or because of

of raw

displayed

products

These two studies reflect the

effort in technology, either in

process

innovation

or product innovation, may change the shape of the PLC.

In conclusion,

from the literature review, the shape and the existence of

the PLC is generally

These deviations

confirmed,

is

not

there

are

some

deviations.

are largely due to efforts of the firms in the areas of

technology and promotion.

the PLC

although

an

Consequently, managers have to be

uncontrollable variable.

aware

that

Because the PLC partially

depends on firms behavior, Dhalla and Yuspeh(1976)

should "forget

the

product

As indicated,

argument.

managers do

life

cycle

the S-shaped

concept".

that

managers

This is not a fair

reflects

curve

if

nothing and let the contagion process proceed naturally.

It

is a benchmark

for planning.

A

efforts

their

a

sales

more beneficial approach is not to forget

the PLC concept, but to use the PLC as

should take

PLC

argue

into

a

base

planning.

for

Managers

account to modify the shape of the PLC

when they utilize the PLC as a planning instrument.

As indicated, the usefulness of the PLC concept is that

capture demand

formulation.

and

If

its

phases

competition patterns which are essential in strategy

the PLC concept is valid, then the next question is what

are the possible characteristics of demand and competition in each

that can be used as a base to formulate competitive strategy?

great deal

has

will present some common suggestions about the

These

Although

a

The 'following section

characteristics

of

each

arguments will then be tested by using the PIMS data base.

THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STAGES OF THE PLC

II.

1.

phase

been written on this subject, very few empirical studies

have been done to support the arguments presented.

phase.

can

Common Suggestions of Characteristics of the Stages of the PLC

After

a

new product has been launched,

change across time.

his 1979

book.

its demand and

supply

conditions

Porter has summarized those changes in each stage

There

is

no

reason to duplicate his work here.

10

in

This

section will only briefly mention several

four stages

attributes

important

the

of

Generally speaking, some writers agree that the

of the PLC.

following phenomena characterize the four stages of the PLC[Kotler ,1980,

Staudt 1976, Levitt 1965, Forrester 1959].

demand needs to be created.

In the introductory stage,

costs are thus substantial.

negative, and

competitors

early

those

limited to

risk-taking.

The

buyer

As a result, profits tend to be low or

are

few.

characterized

adopters

a

even

the growth period, buyers are

In

high-income,

by

group is widening, the product begins to appeal

to different groups and prices are relatively

decline as

Promotion and R&D

higher

The resulting high profits

result of the experience curve.

attract new entrants into the field.

In this stage,

be less then that in the introductory stage.

which

costs

than

promotion cost

will

In the maturity period,

the

opportunities for product improvement had already been exploited, and the

product tends

to

The absence of entry barriers with

standardized.

be

respect to product differentiation causes competition to

intensify,

and

profits fall.

Two kinds of industries may attract increasing international

when they

reach

capital intensive

innovations.

In

maturity

the

industries

labor

stage:

which

intensive

labor

had

intensive industries and

major

experienced

industries,

when

a

standardized and its associated technology becomes widely

locus of

competition

process

product becomes

diffused,

the

production of the product will be determined by relative factor

costs [Vernon 1966].

Therefore, low

labor

11

cost

countries

will

enter

When

industries.

labor intensive

capital

maturity, they are characterized by high

These

past investment.

costs.

cost

fixities

cost

intensive

industries reach

fixities

naturally

resulting

from

lower their marginal

As long as the marginal cost of using old equipment is lower than

the average full cost of using new equipment,

new equipment.

firms will

not

invest

in

Thus, cost fixities prohibit domestic firms from adopting

that would bring average cost down.

process innovations

in the automobile

industry, and continuous-casting method

industry [Rosegger 1979]).

As

foreign

producers

to

be

higher

in

steel

the

produce these capital

intensive goods with new equipment, the average cost of

industries tends

(such as robots

domestic

mature

than that of their foreign competitors.

Such factors attract increasing competition from foreign countries.

Finally, at the last stage, the increasing competition

decline in

demand

cause

the

profits

as

well

as

the

and the number of competitors to

fall.

In sum,

researchers generally agree on the following hypotheses:

.Marketing and R&D expenses will decline as the PLC proceeds

.Products will

be standardized

.Imports from countries with low manufacturing costs will increase

.Competition will intensify

.Profit will be

highest in the growth stage and decline after that

Two questions regarding the rationale of

12

the

above

hypotheses

may

be

The

raised.

first

concerns

question

competition

relationships between profits,

concept.

management's

concerns

second one

assumption

the

demand

grows, competition is not intense, but,

when

competition

stage).

becomes

the

(maturity

fierce

competition cycle, profits

decline stages.

above

the

arguments

in

is

turn,

Specifically, it is assumed that when demand

are tied to the life cycle.

in

The

Therefore, the competition cycle and the profit cycle

determine profits.

period, rise

cycle.

the patterns of competition which,

governs

growth

the

toward the usage of the PLC

attitude

First, an implicit assumption behind

that demand

life

and- the

about

are

growth

low

negative

or

and

stage,

As

in

becomes

a

result

the

stagnant,

of

the

introduction

then fall in the maturity and

These relationships are shown in Figure 2.

Competition

Profitability

Intro.

Growth

Figure

Maturity

^

Time

2

The Trend of Profitability and

Competition in the

Life Cycle

The relationship between competition and profits is well recognized,

the underlying

rationale

of

but

the proposition that demand growth governs

competition has not been clarified.

At an extreme, Porter[1980]

13

argues.

"Except for the industry growth rate, there

is

little or no

underlying rationale for why the competitive changes associated

with the life cycle will happen."

However, Porter ignores an element of the PLC which

and the stages of the PLC-- time.

components

time, two

the

of

relates

competition

To a certain extent, demand growth and

may

PLC,

affect

the competition in the

industry through changing the height of entry barriers.

It

should be noted that whether competition becomes

maturity stage

barriers.

depends

on

rate

the

of

entry,

Two factors may affect the height of

passage of

time,

diffusion

the

intensified

function

a

entry

barriers

It

obvious

is

of diffusion of technology may reduce entry barriers.

in

reduce the

significance

of

scale

of

economies

of

scale

demand,

speed

The second factor,

the

entry

as

barriers.

.

If

MES grows

faster

industry will become concentrated and vice versa.

the

Therefore, the height of entry barriers

to

that

may increase in the passage of time as the

product becomes standardized and is mass produced

relative

the

in

demand, may allow new entrants to reach MES, and in turn,

However, economies

than the

entry

of

of technology and the growth of demand

relative to the minimum efficient scale(MES).

the growth

the

in

MES

growth,

and

depends

the

on

demand

the

diffusion

growth

technology.

of

Consequently, whether the competition pattern changes with the

stage

of

degree

of

of scale,

the

the PLC depends on these two factors.

For example, the U.S.

maturity 25

years

passenger car

ago.

Due

to

industry

substantial

14

reached

some

economies

competition was not strong, and

this

Clearly,

1960's.

theorists.

is

industry

the

not

However, as the demand growth of

overcame the

economies

and

scale,

of

diffused, Japan auto makers were able

compete with

their causes

as

to

Japanese

the

production

the

PLC

technology

market

and

auto

barriers

and

can explain the competition and profitability of the U.

In

it.

in

market

auto'

U.S.

This example shows that entry

auto industry better than the PLC can explain

main reason

the

enter

the

by

Consequently, the profits of the U.S.

the big three.

makers have since declined.

predicted

situation

the

profitable

very

was

conclusion,

S.

the

competition is associated with the stage of the PLC is

that

that entry barriers are affected across

time.

One

must

look

at

the

underlying factors affecting entry barriers to predict future competition

rather than

merely

the the PLC as a predictor of competition and

using

profits.

The PLC concept

useful

is

competition patterns

of the

PLC

is

that

in

important;

not

primary

captures

the

important

question

vs quality competition) change with the stage of PLC.

competition are the primary concerns of managers,

the

long

time.

increased sharply.

Management should

is

how

the

it

Since

is most

demand

and

important to

that affect competition and demand, such as income

factors

and price elasticities.

for a

and

market structure, price competition

competition pattern and demand (e.g.

look at

demand

Therefore, the validity of the shape

its stages.

in

it

As

This

For example, coal had been in the decline

a

result

can

scrutinize

not

of

be

stage

the oil shock, the demand for coal

explained

by

the

PLC

concept.

the determinants of demand and competition

15

.

future demand and competition.

in order to predict

the determinants

competition and demand

of

available, the PLC may then be used as

PLC concept seems to be widely used

because of

convenience

its

in

a

is

When

information

costly to obtain or

is

surrogate tool in planning.

not

because

of

not

The

accuracy

its

on

but

indicating somewhat the future stages of

evolution

Although there

unanimous

is

characteristics of

Table

2.

1

show

among

researchers

about

the

each stage of the PLC, there is a lack of evidence to

support these arguments.

used to

agreement

To fill this gap,

the PIMS data

differences between stages.

the

will

base

be

The results are shown in

and will be discussed in the following section.

Empirical Study of the Characteristics of the PLC

Before discussing the results of our analysis using the PIMS

some qualifications

regarding the data base have to be made.

First,

sample businesses in the PIMS data base are SBUs which supposedly

in only

market.

one

parent companies.

way

of

market scope

of

homogeneous.

This heterogeneity may lead to distortion of

Secondly, many

SBUs,

variables

in

the

measured.

share.

engage

These

defining

definition of the market served

our

the

is not

results.

data base are subjectively measured,

this

such as the stage of the PLC, product quality,

even market

the

The markets served, however, are defined by their

Since each company has its own

its

base,

data

measures

are

relative direct

cost

and

not as precise as objectively

Thus, our results are highly tenuous and one has to keep these

16

deficiencies in mind in interpreting our results.

In the PIMS data base,

the business'

In order to use

the sample businesses themselves.

further

basis for

reported stages by examining

the

check

the

variables

that,

by

By definition,

supposed to change in different stages.

as a

percentage

total

of

newness

sales,

technological change should decline as

of

as

a

validity of the

are

definition,

new product sales

plant and equipment, and

proceeds.

PLC

the

variable

this

first

must

one

study,

stage within the PLC is reported by

s

The

market

growth rate should be highest in the growth stage and decline after that.

In Table 1,

one can observe that all these variables act in the direction

growth rate in introductory stage is

market

expected, except

that

higher than that

in

the

growth

significant (t=0.85,

not

significant)

neglected.

the

stage.

But

and

the

this

difference

is

contradiction

not

may be

Therefore, the stage reported is generally correct and may be

used as a basis for further study.

In the previous section,

it

is

suggested that marketing and R&D expenses,

imports, product standardization,

vary in

different

stages

of

competition,

the PLC.

profitability is shown by three measures:

and

will

profitability

To test these hypotheses, SBUs'

gross margins,

ROI

and

ROS.

The intensity of competition is measured as the inverse proportion of the

largest four firms' market share.

(i)

It

is

found that:

maturity stage(72.1 percent

Most of the businesses are in the

in the growth stage.

(ii) R&D expenses as a percentage of

sales is highest in the

17

)

or

.

introductory stage and decline after that.

The same is true

(iii)

(iv)

Imports as

a

for marketing expenses,

percentage of total market sales increase over time.

Customization declines from the growth stage;

product

standardization increases across time,

(v)

Gross margins are

highest in the introductory stage and decline

afterwards. The high gross margins may be due to the monopoly power

attached to new products.

by high marketing and

R&^D

But the high gross margins are eroded

expenses in the introductory stage.

Therefore, ROI and ROS are the lowest among the four stages.

This result is consistent with Biggidike' s[1979] findings about the

profitability of new entrants,

(vi)

ROI and ROS decline after the growth stage

.

ROI

in

the

growth stage is significantly higher than that in the maturity

stage(z=2.55 significant at

in the

0.01 level). ROS is also higher

growth stage than in the maturity stage, but it is only

significant at 0.05 level (z=l .87)

(vii) The intensity of competition increases in the maturity stage from

the growth stage.

T-test shows that there is significant

difference in the largest four market shares between the

growth stage and the maturity stage(t=2. 31

18

,

p=O.Ol)

)

)

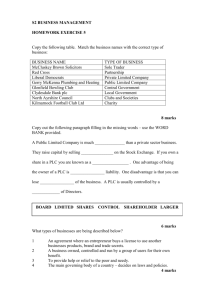

Table

1

Characteristics of the Stages of the PLC

Introductory

No.

of Obs.

MKT GROWTH

% NEW PRODT

PS.E NEWNESS

TECH. CHAG.

R&D/REV.

MKTING/REV

IMPORTS %

CUSTOMZATON

ROI

ROS

GRS MRGIN

MKT CONCEN.

32

Growth

1046

Mean(S.D.

Mean(S.D.

19.84(14.55)

33.68(28.10)

66.17(12.7)

0.75(0.433)

5.06(3.69)

16.56(9.34)

17.63(13.26)

13.78(17.68)

59.29(16.0)

0.49(0.50)

3.08(3.25)

9.92(6.49)

4.16(8.17)

0.296(0.46)

24.89(25.53)

10.23(11.61)

29.99(14.09)

72.81(21.67)

n.a.

0.125(0.33)

3.90(24.88)

-0.75(14.07)

34.69(17.87)

62.60(21.84)

Maturity

3554

Mean(S.D.)

10.63(10.18)

6.77(13.05)

52.60(14.6)

0.20(0.40)

1.78(2.21)

8.73(6.73)

5.66(10.2)

0.21(0.41)

22.68(21.42)

9.50(9.04)

25.88(12.10)

71.05(21.71)

Decline

231

Mean(S.D.)

F

6.61(9.94)

3.55(6.09)

45.21(14.7)

0.22(0.41)

1.15(1.68)

8.31(5.92)

12.82(15.2)

0.12(0.33)

15.06(19.1)

5.69(8.43)

19.83(11.5)

69.64(23.3)

143(0.001)

110(0.001)

87.6(0.001)

132(0.001)

101(0.001)

23.1(0.001)

13.3(0.001)

17.6(0.001)

20.0(0.001)

25.8(0.001)

54.7(0.001)

3.96(0.008)

(P)

Definitions; MKT GROWTH: Served market annual growth rate

P&E NEWNESS: Net book value/gross book value

% NEW PRODUCT: Percentage of total sales accounted

for by products introduced during last 3 years

TECH CHAN: Equals 1 if there have been major technological changes in the last 8 years and zero otherwise

R&D/REV: R&D expenses as a percentage of sales

MKTING/REV: Total marketing expenses as a percentage

of sales

IMPORTS %: percentage of imports in served market sales

CUSTOMZATIN:Equals 1 if the SBU designed or producedto

orders for individual customers and zero otherwise

ROI: Pretaxed income over invested capital

ROS: Pretaxed income over sales

GRS MARGIN: Gross marqins= Sales-di rect costs-deprec iation

Sales

MKT CONCEN: Largest four firm market share

19

F-tests show that all these variables are significantly different

agreement

Thus,

four stages.

in

the

among researchers on the characteristics

are generally confirmed.

In conclusion, despite

the

deficiencies, it

govern

environment.

does

characteristics

some

following

The

of

that

fact

suffers

PLC

businesses'

of

sections

separate

the

the

discuss

stages

behavior and their

how

the

of

certain

from

PLC

different

the

affect

generic

competitive strategies.

An SBU's strategy should be formulated based on trends in the environment

and its own strengths and weaknesses.

the PLC is a good indication of

Therefore, the

trends

the

environment.

SBU's

an

in

phase of the PLC partially shapes the strategy of an SBU.

In addition to the phase

influence an

As indicated, the current phase of

SBU's

PLC,

of

strategy.

length

the

of

the

will

PLC

also

example, an SBU in an industry with

For

short PLCs should have enough flexibility

cope

to

with

product

rapid

innovations introduced by the SBU and its competitors.

The following sections examine the effects of both the phase

of the

PLC

on

an

SBU's

strategy.

The

definition of generic strategy and develops

generic strategies

in

a

particular

first

a

industry.

section discusses the

methodology

section

looks

at

the

effects

generic strategies.

20

of

to

identify

The second section then

analyzes the appropriate generic strategies for each stage

The third

length

and

of

the

PLC.

the length of the PLC on

III.

1.

THE DEFINITION OF GENERIC STRATEGY

The Definition of Generic Strategy

Two main approaches concerning generic strategy emerge from the

the

"process"

approach

and

process approach

primarily

concerns

generic

literature:

process.

[Miles

and Snow, 1979;

approach focuses on

describing organizational

"content" approach.

the

types

of

processes

a

are

strategy.

our

(

literature.

generic

and

strategy

,

the concept of generic

strategy

,

the content approach, has seldom been discussed in management

states

Porter

giving

consistent," without

generic

that

a

definition

describes three generic strategies-and focus--

variables

Since

results with those studies using the process approach.

Since being proposed by Porter 1979)

which uses

The content

not available in the PIMS data

base, we will adopt the content approach to study

then compare

The

organizational

of

Miller and Friesen, 1978].

components

the

strategy

based

two

on

strategic advantages.

It

cost

strategy

of

is

"internally

He then

the term itself.

leadership,

differentiation,

strategic dimensions :market segmentation and

is not clear

from

description

this

what

the

term generic strategy means or how this concept relates to other concepts

of

strategy.

The generic strategy of an SBU reflects an integrated view of

strategic behavior.

decisions;

It

originates

from

the

hierarchical

some decisions govern other decisions.

21

(

the

SBU's

nature

This character

of

has

extensively

been discussed

literature

the

in

Ansoff 1965, Hofer and Schendel 1978].)

the highest

decision

leadership, for

competition),

market(

product

.

the

hierarchy.

strategic

Dr.

,

as

Consequently,

decisions.

Cost

result of decisions about the

market),

competition

standardized

product),

pattern(pr ice

and

focus

Another example is Polaroid's early

exploit

to

i.e.

mass

design{

production (efficiency ), etc

strategy,

other

determines

example,

target

all

defined

Generic strategy is

decision

the

in

dominates

generic strategy

selection of

made

[March and Simon 1958

on

generic

Land's invention, the instant camera.

Sears' previous generic strategy was to provide quality

good service with relatively low prices.

merchandise

and

P&G's generic strategy is based

on the concept of mass marketing a relatively low-priced quality consumer

product line through supermarkets.

As the choice of the SBU's generic strategy will determine

the SBU's strategic decisions,

decisions of

it tends to

the

rest

of

integrate all of the strategic

an SHU into a coherent one and in doing so, creats internal

consistency among decisions.

Generic

between strategic

and

decisions

strategy

specifies

relationships

thus provides an integrated view of an

SBU's strategy.

The generic strategy defined above differs from the strategy

Ansoff(l965) and

Hofer

latter suggest that

a

and

Schendel s(l978

'

)

in one

major aspect.

strategy consists of four components.

generic strategy of an SBU governs these components.

concept

For

of

The

However, the

example,

the

generic strategy of cost leadership not only specifies the product-market

22

served, and

the

competitive

employment

the direction of resource

choice of

advantage chosen (price

but also dictates

,

)

reduction

(cost

oriented).

The

the generic strategy is a decision made prior to the decisions

regarding these components.

Three dimensions used to describe

and market share acquisition.

classification

of

dimensions

The first two

strategies.

generic

the

of competitive advantages,

selection

segmentation,

literature-- market

Porter's

generic strategy may be found in

a

originate

The

three

from

generic

strategies suggested by Porter, cost leadership, product differentiation,

and focus, are formulated based on market

advantages.

Cost

leadership

is

segmentation

strategy

generic

a

and

competitive

which treats the

market as an aggregate without recognizing the different market

and which

chooses

cost as its competitive advantage.

low

position is usually achieved by a mass production method.

differentiation strategy,

advantage and directs its sales to the

focus targets

quality

chooses

SBU

the

entire

market.

The low cost

In

as

segments

a

A

a

product

competitive

strategy

of

on a narrow market segment and chooses price or quality or

The market scope of a

both as competitive advantages.

"focus"

strategy

is narrower than that of the previous two generic strategies.

These three

generic

leadership

and

strategies

the

"focus"

are

strategy,

differentiation can coexist;, product

strategy are

only

different

not

mutually

and

cost

differentiation

Cost

exclusive.

and

leadership

and

the

"focus"

in the degree of market segmentation.

example, Japanese auto makers focus on the small car

23

market

and

For

choose

both price

quality as competitive advantages.

and

achieved by employing

strategy combining

cost leadership strategy.

a

cost

leadership

and focus.

the medium car market and the large car market,

will be

If

adopt

they

Thus,

a

they gradually enter

their

strategy

generic

best described as "product differentiation and cost leadership."

The third dimension, market

approach which

assumes

acquisition

share

high

that

Schendel 1979]

Hofer and

[

acquisition and

absolute

business strategies.

have

used

to

increase

market

describe

to

increase

share

positively related to absolute investment,

merged into

market

share.

the

two

six

generic

type

is

assumed

to be

dimensions

Thus, the six generic strategies reside on

one.

BCG

the

in

these two dimensions, market share

investment,

Since

originates

market share leads to high long-term

profitability and that investment is needed

of

Their low prices are

can

be

continuum

a

offensive-defensive-liquidation strategies, with market share increase

strategy at one extreme and liquidation(giving up market

other end.

continuum

This

at

the

dimension which describes

third

the

is

share)

a

generic strategy.

There are

many

combinations

combination is

a

acquire market

share

unique

of

these

generic

through

a

strategy.

product

through a cost leadership strategy.

exploratory study

and then

,

examine

generic strategies

to

three

dimensions

For

and

example,

differentiation

each

an SBU may

strategy

or

Thus, the next step is to conduct an

find feasible generic strategies employed by SBUs,

the

difference

described

between

above.

24

"real"

and

In the next section,

"theoretical"

a

methodology

is

2.

developed to identify the generic strategies used in an industry.

The Methodology of Identifying Generic Strategies

The generic strategy determines subsequent strategic decisions which

be measured in terms of strategic dimensions(e.g.

Assuming

expenses).

R&D

integration,

transformation from

a

the degree of vertical

there

that

SBUs adopting

dimensions.

strategic dimensions between SBUs, one can

employed by any one SBU in

SBU

dimension is

a

the "similarity"

in

an

its

similar generic strategy

a

identify

way described below.

a

N-dimension

of

euclidean

strategies.

their

the

Since

between

distance

space

which

in

these

the

SBUs

dimensions

is a

The

more similar are the strategies adopted.

several generic strategies in

between the SBUs

strategies

generic

distance" which reflects their strategic similarities.

the

along

behavior

each

strategic dimension, the distance between SBUs indicates

strategic dimensions,

distance is,

unique

a

Thus, based on the similarity of

must have similar strategic dimensions.

Placing each

is

generic strategy to subsequent strategic decisions,

the generic strategy of an SBU can be inferred from

several strategic

can

adopting

a

are

"strategic

smaller

If

the

there are

group of SBUs, there are larger distances

different

generic

strategies,

and

smaller

distances between the SBUs adopting similar generic strategies.

Cluster analysis matches the idea

inference as

described above.

of

identifying

generic

strategy

by

Cluster analysis places each object in an

25

N-dimension euclidean space and then clusters objects into

on the

distance

between

objects.

the

The

groups

criterion

clusters in this study is minimum squared error (MSE).

based

used to select

The MSE method is

to select the two clusters to be merged at each stage in such a way as to

minimize the mean squared distance between an individual

point

and

the

centroid of the cluster to which it will be assigned after the merger has

been affected.

The dimensions used here to describe each subject are the components of

strategy;

the difference in the components of strategy between groups is

assumed to be an

strategies.

strategy:

indicator

Hofer

product-market

synergy.

engaged

market,

in one

component are

of

difference

the

Schendel [1978]

and

advantage, and

scope,

Since

the

neglected.

suggest

resources

each

synergy

between

four

their

generic

components

deployment,

Resource deployment:

1.

business in the PIMS data base is

component

and

the

product-scope

The dimensions of the remaining two components

Degree of vertical integration: the ratio of

value added to total revenue.

B.

2.

Process R&D expenses / Revenue.

3.

Product R&D expenses/Revenue.

4.

Sales force expenses/Revenue.

5.

Promotion expenses/Revenue.

Competitive advantages

of

competitive

used and their definitions are the following:

A.

a

6.

Newness of plant and equipment: net book

value P&E/ Gross book value P&E.

26

Relative product quality: percent product

7.

quality

superior minus percent product

quality inferior.

8.

Relative price: percent relative prices

vs. competitors.

9.

New product% :percent of new product sales

to total sales.

10.

Relative direct cost

percent relative

:

direct costs per unit vs. competitor.

Applying cluster analysis

results in

to

an

based

industry

dimensions

these

on

grouping of SBUs adopting similar generic strategy.

a

Since

the groups are identified based on strategic dimensions, these groups are

called "strategic groups" [Porter

1979].

Porter

postulates

that

the

If

this

strategic groups in an industry exhibit performance differences.

hypothesis

correct,

is

different performance.

proposition either

use

different

generic

However, the empirical

size

,

and

Schendel

proposition, we will examine

lead

validating

studies

to

this

as the only strategic dimension to cluster

SBUs[Porter 1979 Stonebraker 1976], or use an

model[Hatten

will

strategies

To

1976].

the

statistical

inappropriate

correctly

performance

validate

differences

Porter's

between

the

strategic groups identified by cluster analysis.

The generic strategies described in the previous section

clearly

affect

these dimensions.

A strategy of cost leadership must have relatively low

price and

two important competitive weapons.

costs,

27

The product should

be standardized to fit

involve less

production

mass

and

RS.D

vertically

may

realize their economies of scale.

advantage

there

expenses should be relatively high.

Vertical integration may be either high or low.

leadership strategy

therefore,

Consequently, product R&D expenses should

product changes.

To reduce costs, process

be low.

methods

integrate

SBUs

adopting

backward

cost

forward to

or

However, SBUs using the same

purchase

a

strategy

exercise

their

bargaining power to lower their purchasing prices and thus, reduce

their

may

take

degree of

vertical

their

of

size

of

Therefore,

integration.

integration is not solely determined by

Finally,

the

cost

the

and

degree

of

leadership

vertical

strategy.

cost leadership strategy should lead to a higher market share.

a

As for the product differentiation strategy, Porter

strategy requires

quality and

high

By definition,

prices.

this strategy depends on the

product quality.

that

The

high

marketing

expenses

this strategy should have high product

vertical integration is affected by

Whether

contribution

of

vertical

integration

it has a

the

in the

Second,

different

to

limitations of the methodology and the PIMS data base.

First, the strategic dimensions used in the present

inclusive.

to

smaller market share.

Before discussing the results of our analyses, again, it is necessary

of

and

strategy of "focus" is similar to the strategy of

product differentiation, but

be aware

this

"strong marketing abilities" and "product engineering"

or "technology leadership", which lead to

high R&D expenses.

suggests

paper

are

not

all

the importance of these dimensions to the competition

industries

should vary.

28

However, no attempt has been

.

weights

made to give

some

to

dimensions

to

reflect

relative

their

importance

Based on 10 strategic dimensions, cluster analysis has been performed for

the chemical industry(SIC 28).

The main reason for choosing

a

particular

industry as the unit of analysis is to avoid the heterogeneity of

reason

The

behavior.

the chemical industry is that its

analyzing

for

firms'

sample size is the largest among the 2-digit SIC industries in

the

PIMS

data base.

3.

Empirical Results

The results

presented

of

Table

in

cluster

the

2.

is

chosen

at

of

the

chemical

the

of

cluster

the

where

level

of

objects

in two of

The

analysis.

mean

error

square

substantial increase resulting from the merger of two

the number

industry

are

Five groups of SBUs in the chemical industry were

chosen from the dendrogram

cluster

analysis

groups.

number

of

shows

a

However,

the groups in the chemical industry is

too small and so are excluded from the discussion.

As

a

result,

only

three groups are presented in the table.

In Table 2, the three major groups exhibit differences across most of the

strategic dimensions.

SBUs in group one adopt high vertical integration,

high R&D, heavy marketing intensity high product quality, high price

,

low cost

strategies.

and

The "internal consistency" of those strategies can

The SBUs in group one focus on high

be interpreted in the following way.

29

product quality and high price market.

The superior product

quality

is

achieved by high product R&D expenses, new equipment, heavy marketing, or

high degree

of

vertical integration (an important factor in the chemical

Because of superior product quality, these SBUs are

industry).

raise their prices and gain higher profits.

from high

to

High profits result not only

but also from low cost which is made possible by high

prices,

and

process R&D expenses

expenses and

able

product

new

low

low

new

product

High

sales.

process

R&D

indicate that the SHU exclusively

sales

focuses on the improvement of the production process of existing products

and not new products.

This internal consistency between strategic dimensions is the

the generic

adopted

strategy

strategy may

be

called

"low-profile" strategy

by

the

SBUs

"high-profile"

adopted

by

group

in

strategy,

group

3.

completely different strategies from the SBUs in

they also have no new product sales.

strategy.

These

three

generic strategies.

groups

group

SBUs in group

illustrate

three

2

group

in

of

This generic

1.

opposed

as

SBUs

result

1,

to

the

3

adopt

except

that

adopt an in between

internally consistent

Both the high-profile strategy and

the

low-profile

strategy show patterns similar to the product differentiation strategy as

described before,

but

one strategy differentiates itself from others by

its high product quality and the other by its low product quality.

30

Table

2

The Strategic Groups in the Chemical Industry

Group

No. of Obs

1

Group

17

2

Group

3

66

44

MEAN(S.D.)

MEAN(S.D.)

STRATEGIC DIMENSIONS (STANDARDIZED)

MEAN(S.D.)

REL QUALITY

REL PRICE

VERT INTEGRTN

PROD R&D/REV

PROC R&D/REV

SALES FRC/REV

ADV& PROMO/REV

P&E NEV7NESS

REL DIR COST

10.% NEW PRODUCT

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

0.68(1.45)

1.16(0.19)

1.14(0.20)

1.97(0.61)

1.30(0.46)

0.92(0.78)

-0.07(0.08)

0.87(0.65)

-1.45(0.19)

-0.43(0.0)

0.23(0.97)

0.18(0.90)

0.33(0.82)

-0.20(0.56)

-0.30(0.55)

0.25(0.97)

-0.12(0.25)

0.08(0.80)

-0.01(0.46)

0.00(0.62)

-0.54(0.38)

-0.48(0.67)

-0.87(0.67)

-0.59(0.44)

0.15(0.24)

-0.87(0.39)

-0.29(0.02)

-0.57(0.38)

0.47(1.25)

-0.36(0.22)

PERFORMANCE

1.

2.

ROS

3.

MARKET SHARE

ROI

27.46(8.89)

36.05(19.08)

25.41(22.99)

16.98(11.29)

31.66(20.44)

29.05(20.11)

31

10.15(9.98)

24.16(18.40)

28.23(20.18)

)

)

Table

)

(CONTINUE)

2

The Strategic Groups in the Chemical Industry

Group

No.

of Obs

Group

4

4

5

5

STRATEGIC DIMENSIONS (STANDARDIZED)

MEAN

REL QUALITY

REL PRICE

VERT INTEGRTN

PROD R&D/REV

PROC R&D/REV

SALES FRC/REV

ADV&PROMO/REV

P&E NEWNESS

REL DIR COST

10.% NEW PRODUCT

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

(

S

.

D

.

-0.97(0.60)

-2.21(1.15)

0.53(0.39)

-0.71(0.06)

-1.00(0.00)

0.78(0.36)

5.53(1.04)

0.50(0.71)

1.30(0.17)

-0.50(0.42)

MEAN

(

S

.

D

.

0.07(0.78)

-0.51(0.18)

-1.10(0.24)

1.65(0.36)

-1.00(0.00)

0.44(0.46)

-0.15(0.13)

0.38(0.91)

-0.17(0.18)

4.47(0.47)

PERFORMANCE

1.

2.

3.

ROS

ROI

MARKET SHARE

F

(

8.4(0.001)

23.2(0.001)

34.6(0.001)

90.0(0.001)

15.9(0.001)

22.4(0.001)

490(0.001)

9.0(0.001)

20.2(0.001)

128(0.001)

F

4.57(2.49)

14.52(4.24)

5.63(2.33)

5.66(1.07)

16.96(2.53)

14.90(3.15)

32

P

(P)

11.1(0.001)

"2.61(0.038)

1.8(0.113)

r'

0.253

0.074

0.052

.

Interestingly enough, as observed from Table

these

2,

three

strategic

groups show performance differences in terms of return on sales (ROS) and

investment

return on

F-tests

(ROI).

show

that there are significant

differences in ROS(at 1% level) and ROI (at

3.8%

high degree

SBUs in group

vertical

of

integration

of

asset turnover rates, and thus, there is no

ROI between

2

is

group

and group

1

higher than that

proposition

Therefore, the

significant

However,

1

the

reduces their

differences

in

But T-test shows that the ROI of group

2.

group

of

level).

at

3

significance

5%

level (t=2 16

.

)

that strategic groups in an industry exhibit

performance differences is generally confirmed.

Due to

the

differences

technological progress,

industries, the way

demand

different

pattern)

"internal

different between industries.

will be

across

sales,

is

Total

intensity as

a

(economies

market

is

scale,

of

structure between

constructed

should

be

Thus, the patterns of the generic strategy

industries.

To

the

to

test

this proposition, the

machinery

industry(SIC

35).

R&D intensity as it accounts for less than 0.5 of total

excluded from the

analysis.

and

consistency"

methodology used above is applied

However, process

conditions

basic

in

R&D

strategic

expenses

substituted

is

strategic dimension.

dimension

used

for

in

the

cluster

the

product

The results are presented

in

R&D

Table

3.

Based on nine strategic dimensions, six groups were identified

four groups

objects.

are

Again,

discussed;

two

groups

contain too

a

but

small number of

"high profile" and "low profile" generic strategies

33

only

are

Group

found.

adopts

1

high profile strategy and shows high degree of

a

vertical integration, high R&D and marketing intensity and

group

However,

quality.

only charges medium price

1

and thus obtains significantly

competitors;

high

,

high

product

relative to its

market

share

(47%).

This high profile strategy is different from the high-profile strategy in

the chemical

Newness

industry.

and equipment, and relative

plant

of

direct cost are not associated with the rest of strategic dimensions.

Group

2

adopts

Group

strategy.

group

2,

a

group

price, low

4

low-profile strategy and group

however,

4,

shows

an

Moreover,

strategy.

inconsistent strategy.

its

new

product

relatively high, and its marketing expenses are very low.

new products

do

not

have

necessary promotion.

The inconsistency in

poor performance

the

of

SBUs

in

As

Unlike

its

low

sales

are

result,

a

enough marketing budget to conduct

large

a

in-between

an

its direct costs to match

is not able to lower

quality

adopts

3

group

strategies

4.

results

very

in

Their ROI and ROS are the

lowest among the four groups.

As far as the performance is

industry, SBUs

in the

concerned,

unlike

machinery industry adopting

SBUs

a

in

the

chemical

low-profile strategy

are as profitable as SBUs adopting a high-profile strategy.

Both groups'

ROI are 28% and are significantly higher than the group 3's ROI at

level and group 4's ROI at

a

1% level.

34

a

5%

)

Table

3

The Strategic Groups in the Machinery Industry

Group

of Obs

No.

1

Group

Group

2

62

32

3

18

Group

4

23

STRATEGIC DIMENSIONS (STANDARDIZED)

MEAN(S.D.)

REL QUALITY

REL PRICE

VERT INTEGRTN

TOTAL R&D/REV

SALES FRC/REV

1.315(0.58)

0.13(0.60)

0.78(0.69)

1.42(1.12)

0.96(1.12)

ADVtPROMO/REV -0.07(0.45)

P&E NEWNESS

-0.30(1.14)

REL DIR COST

-0.08(0.64)

9.% NEW PRODUCT

-0.23(0.44)

^10. TOTAL MKTING/REV13.51(7.06)

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

MEAN(S.D.)

-0.35(0.60)

-0.10(0.62)

0.09(0.78)

-0.53(0.52)

-0.22(0.78)

-0.47(0.27)

-0.16(0.73)

-0.55(0.59)

-0.24(0.43)

8.68(4.58)

MEAN(S.D.)

0.13(0.63)

0.19(0.90)

-0.08(0.74)

0.13(0.59)

-0.16(0.56)

2.15(1.40)

0.12(0.63)

-0.06(0.47)

-0.18(0.33)

13.39(4.52)

MEAN

(

S

.

D

.

-1.13(0.40)

-0.95(0.43)

-1.12(0.94)

0.14(0.80)

-0.55(0.26)

-0.21(0.27)

0.46(1.29)

0.57(0.93)

0.37(0.87)

6.13(1.65)

PERFORMANCE

1.

2.

3.

ROS

ROI

MARKET SHARE

''^Not

13.90(9.42)

28.6(17.0)

46.7(20.6)

11.94(10.55)

28.9(26.3)

29.7(19.5)

Standardized

35

4.57(12.0)

16.2(20.4)

21.5(11.3)

3.37(5.14)

8.88(10.5)

14.1(9.61)

)

)

Table

)

(CONTINUE)

3

The Strategic Groups in the Machinery Industry

Group

I

No.

of Obs

Group

5

10

6

4

STRATEGIC DIMENSIONS (STANDARDIZED)

MEAN

(

S.D

.

REL QUALITY

0.19(0.94)

REL PRICE

2.41(0.44)

VERT INTEGRTN -0.86(0.59)

TOTAL R&D/REV

0.19(0.39)

SALES FRC/REV -0.83(0.46)

ADV& PROMO/REV -0.35(0.44)

P&E NEWNESS

0.05(1.12)

REL DIR COST

2.51(0.16)

-0.40(0.10)

% NEW PRODUCT

»^10. TOTAL MKTING/REV4.12(3.47)

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

MEAN

(

S

.

D

.

0.05(0.10)

-1.02(1.42)

1.12(0.46)

2.83(1.78)

1.35(1.33)

0.09(0.22)

1.33(0.34)

-0.35(0.00)

5.00(0.55)

23.5(1.57)

PERFORMANCE

1.

2.

3.

^'Not

ROS

ROI

MARKET SHARE

F

(

44.4(0.001)

37.9(0.001)

20.0(0.001)

17.5(0.001)

16.2(0.001)

56.3(0.001)

3.57(0.005)

43.7(0.001)

83.1(0.001)

17.6(0.001)

F

8.22(2.88)

18.25(8.06)

10.9(4.33)

13.15(2.60)

25.72(6.69)

46.0(22.80)

Standardized

36

P

(P)

5.11(0.001)

4.00(0.001)

13.6(0.001)

IT

0.152

0.123

0.322

In conclusion,

identified.

strategic

four

groups

machinery

the

in

industry

are

profile strategy and high-profile strategy are equally

Low-

profitable and their profitability is higher than that of the strategy

the

results

These

worst.

strategies

inconsistent

The strategic group with

the middle.

confirm

proposition

the

that

in

performs

different

strategic groups perform differently.

Comparing the results of these two

generic strategy

industry is

process

a

.critical in operations.

because

example,

For

manufacturing

Thus,

high-profile

the

industry is slightly different from

machinery

industry.

chemical

the

that of

the

of

studies,

industry

the

chemical

industry, vertical integration is

integration

vertical

an

is

important

strategic decision which is included in the high-profile generic strategy

in the

SBUs

industry.

the chemical industry, but not in those in the machinery

in

importance

A discriminant analysis revealing the

of

vertical

the chemical industry has been performed by using the ten

integration in

strategic dimension as right-hand side variables.

is the strategic

group of which the SBU

vertical integration

is

the

most

is

The dependent variable

member.

a

degree

The

of

important variable in discriminating

SBUs into the strategic groups created by the cluster analysis.

The otherwise

similar

demonstrate that

price,

generic

strategies

industries

two

the

quality, R&D intensity, and marketing intensity

are usually considered at the same time

generic strategy.

Depending

dimensions to

competition

the

in

upon

in

the

a

37

as

and

form

importance

particular

the

of

basis

of

a

these strategic

industry,

vertical

integration, relative

cost,

and other strategic dimensions may be added

to this basis.

Strategic grouping is actually

Many typologies

aspect

integrated view

Snow' s[l979]

businesses

Rogers[l971]

adopting behavior.

only one

,

typology of the

SBUs

in

based

categorized

businesses

However, most of the

of

SBU's behavior.

organization

an

of

and

an

Burns

and Stalker s[ 1961

found two types of organization:

place

innovation

emphasis

on

Typologies that can provide an

can

'

their

by

typologies

For example,

technological

their

on

industry.

an

can be found in the management literature.

Ansoff[1965] classified

leadership.

a

found

be

]

organic and

studies.

Miles

in

and

Burns and Stalker

mechanic.

Based

on

the

process of adjustment to environmental changes, Miles and Snow identified

four generic

types

of organization:

defender, prospector, analyzer and

Defenders focus on improving efficiency of existing operations.

reactor.

Prospectors seek new products to match market

are in

the

middle

either ends.

the

of

Reactors

adjusting processes.

show

Miles

opportunities.

Analyzers

continuum with defenders and prospectors at

inconsistent

and Snow have

and

a

unstable

behavior

in

detailed description of the

internal consistency among organizational processes for each generic type

of organizations.

their study:

However, only two strategic dimensions are included in

new product sales and costs.

The major difference between our strategic group typology and

studies is

the

kind

of

variables used to cluster SBUs.

group typology uses the "content" of

a

38

these

two

The strategic

strategy to find a typology, while

organizational

the other studies use

the

Despite

typology.

difference,

processes

variables

findings

the

are

similar

aspects.

First, all three studies found a continuum, although

ones, to

categorize

existence

The

SBUs.

of a

in

terms

of

in two

continuum reflects the

which

at

the

the

chemical

to

However,

dimensions

is

only

a

performance

good

internally

industry,

strategy also results in poor performance.

among strategic

the

performance.

indicate the importance of internal consistency.

internal consistency per se does not lead

observed in

in

Second, this study and MS^S's studies

same time.

found that a set of inconsistent strategies results in poor

These results

are

content or strategic processes.

strategy

Without internal consistency, strategic dimensions will not move

same direction

a

different

existence of internal consistency among strategic dimensions,

measured either

reach

to

as

was

consistent low-profile

consistency

internal

Thus,

necessary, but not

a

sufficient,

condition for success.

IV.

GENERIC STRATEGIES AND THE STAGES OF THE PLC

The discussion of the nature of marketing mix to be employed by

phase is

vast

[Kotler, l980;Staudt, Wasson, 1974].

agreement can not be found in the literature,

agree that

PLC.

marketing

most

This

marketing

theorists

mix should be different in the different stages of

PLC

seldom

is

section attempts to derive some hypotheses regarding the

generic strategy in each of the PLC

summary of

PLC

Although conclusive

However, the overall strategy in each stage of the

examined.

the

stages.

It

begins