Basement

advertisement

Basement

:,ji>-^^<^^us^

V

HD28

The International Center for Research on the

Management of Technology

First

in Financial

Mover Advantages

Service Innovations

Luis E. Lopez

Edward

B.

Roberts

Sloan

I

We

2

WP

October 1997

2

^

WP#

#

167-97

3991

INCAE

MIT Sloan School of Management

appreciate funding assistance provided by

Research on

the MIT International Center for

and the

(ICRMOT),

of Technology

INCAE

the Management

MIT Center for Innovation

Product Development

EEC-9529140,

(National Science Foundation Grant #

October 1, 1996).

in

1997 Massachusetts Institute of Technology-

Sloan School of Management

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

38 Memorial Drive, E56-390

Cambridge, MA 02139-4307

FEB osigt

Abstract

A

well-established stream of research indicates that innovative firms must careliilly time

their entry into

new

markets, and that there are advantages to early market entry.

Such

empirical regularity has not been extensively tested in financial services, despite the

importance that the timing order of market entry might have for financial innovations.

Such importance derives

This

innovators.

fi^om the

characteristic

approach toward appropriation.

debit cards,

in financial

other

and pension

industries,

traditional

flinds),

services innovations.

particularly

weak

leaves

appropriability regimes faced by financial service

innovators

Analyzing three

we

lines

find important

These

with pioneering

of

financial

as

an

important

products (credit cards,

market share advantages to early entry

results are in line with other research

consumer products.

We

find,

model of order of market entry doesn't convey

all

performed

in

however, that using a

the information that

is

revealed through a detailed qualitative analysis of longitudinal data.

Moreover, traditional

models of order of market entry do not distinguish simultaneous entries fi"om entries

separated by long periods of time. A model using elapsed time since first entry seems

more appropriate and renders stronger

We

results

and better interpretations.

thank Professors Donald Lessard and Scott Stern for their

and suggestions.

Please direct questions or

comments

Luis E. Lopez

Apartado 960-4050

Alajuela, Costa Rica

e-mail: lopezl@mail.incae.ac.cr

to

many

thoughtfijl

comments

-]

in financial

advantages

se.,ces^

examine

To answer ..s ,ues„cn we

,he relations.,

products.

for a set of financial

long term n.arke. share

and

en.^

market

between order of

literature on pioneenng

provides a review of the

paper

the

of

pan

firs,

Accordingly, the

fo^ulate hypotheses and

second pan we

,„ ,he

.Kem

This

first entr^:

is

for test.ng

prov.tie a research design

and conclus.ons

followed by data analysts

,n

var.ahle pernnts ^uali^.ng

as an .ndependent

Our

findtngs tndicate a negat.ve

more

detati

such relat.onsh.p

Literature

InUoductioimidRe.vi'-w "' "i"

The

.Hare for

brand

and long term market

order of nnarke. en,,,

between

relauonsh.p

en,p,r,ca,

Urban ,1,92, analyzed ,8

new products

,s

well-established

product

entrants in S different

,n,o

,„at later entrants

i.,ance, as shown

in

new markets

Table

.,

m

Kalyanaram and

packaged goods and found

categones of consumer

suffer long-term

market share d.sadvantages,

For

the ptoneer

brands in the market,

the presence of 7

occur only through advantages

whether such advantages

,n

producon

costs, advents.ng,

for

to find after correcting

the product hne, only

of

breadth

and

pnce ,ual.ty, distnbutton,

an

imponant, and to d.scover

infiuences are not

such

that

vanables.

,He effects of those

for late entl^.

apparently inherent penalty

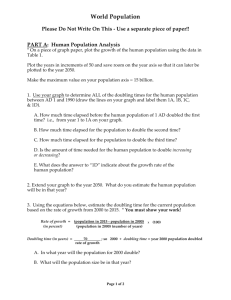

Table

1.

Order of entry

vs.

market share (Taken from Kalvanaram and Urban. 1992)

advantages

A .nmm^rv of some selected emEiri^^' studies on pioneering

T.hiP o

Characteristics of the study and findings

Study, year

Bond and Lean,

1

977

Reviewed

first

1

1

new

entrants maintained market share leadership

years in market

Found

producb. in two prescnption drug markets

after

more

that

10

tlian

Later entrants needed to otTer substantial additional

benellts to surpass the first-mover.

held over

Studied 7 cigarette markets and found that pioneenng brands

Wluttcn, 1979

50%

of the market several years aller

llieir

introduction.

These cigarette

and widely

brands were also those which were actively promoted

dislnbuted.

Kohiiison and I-onicll, 1985

Anahyed

Irbun cl al

1

,

average,

first-

market share of

movers had a market share of 2(1%. early followers had a

17%, and

I

On

mature consumer goods businesses.

.''71

late entrains licld

1

3%

of the market

hnportant penalties

Aiialwed 129 enlnes across 34 product categones

for product

controlling

Table

(see

)

entrants

were reported for late

9S6

1

positioning and marketing

Robinson,

.ambkin,

1

activity.

Analwed 1209 mature induslnal goods manufactunng

9X8

businesses. Tlie

Earlv Ibllowers and

market pioneer holds 29% of the market on average.

respectively

market

the

15%

of

and

late entrants retain 21%

on29

Considered 2 subsamples

I'JHK.

start-up businesses (data for their

first

1X7 adolescent businesses (data for their

fi.ur years of operation) and

an important market

second lour years of operation). Pioneers attained

vs. 9.7% for

pioneers

96"/n

for

(23.

entrants

advantage over later

share

m

late entrants

start-up

subsample and 32.56%

vs.

12.95%

m

the

adolescent subsample).

Lihcn and Yium,

l')9().

The likelihood of success

for first

and second entrants was lower than

and fourth entrants in a sample ol

the likelihood of success for the third

112

Colder and

Tellis. 1993.

1

994

Hutr and Robinson, 1994

industrial products

from 52 French firms.

Using an historical approach found

m

Brou-n and Lattin,

new

success.

They

Modeled the

report a

efiect of

47%

time

pioneenng

may

Re-anaK-zed Urban

el al "s

product categones

Found

efforts

market on pioneering advantage

exert a beneficial efiect

that lime-in-market

market share reward

in

that not all

ended

failure rate for pioneers.

Found

upon the pioneer

(1994) data on 95 surviving brands in 34

that longer lead-time increases the pioneer's

appear .o be qu,.e consistent

acoss many produc,

lines,

as can

be seen

.n

Table

2.

generalizations that applied

(1995) summarized some

Urban

and

Robinson,

Kalyanaram.

,0 prescriptton ami-ulce.

reproduced

in

Table

goods

dmgs and consumer packaged

These generalizations are

3.

OrdeorfjMlVfl^MIX^ncLl^^

Tables

^i^escri^tionmTtiriilcer drut;L

-p^;7;::;:^;q77;ri^ ^h.re Relative"^ the

-}

Pioneerin£B7^nd__

"

'

Prescription Anti-

UlcerDrm^s

ConsumerPackaMed^oodi

Kalyanaram and

Rerndlelal(1994)

Urban (1992)

L„.le

work

has deal, with services

existence of

nnancal mnova.ions, the

Tnfano (1989) found,

,He

life

,<,S9:

23.)

He showed

remam consistent

such advamage seems .o

of the product.

The same

innova.ions

imi.a.ions .ban wi.h

firm

sample of 58

pa.icularly

son,e first-mover advantages,

and marke.tng

.rad.ng, underwntmg,

form of lower costs of

„„f,„„

for a

,s

shown

in

,n

.ha. p.oneers

subsequent years of

less share

.0 cap.ure subs.an.ially

This can be observed

in

Table

4,

the

w„h

pnces for underwriting

p.oneers did not charge higher

Tufano's data showed that

market

prices, generated larger

charging s.m.lar or lower

than later entrants, and, by

from lower costs of trading and

advantages were reaped primanly

shares. Thus, pioneer

accrued through higher pncing.

not from mcreased revenues

from secondary trades and

prov.des banks w.th sources of

suggests that innovation

Tufano's (1989) study

search

to reduce information

.nformafon that allow them

difficulties

involved

in further pioneering.

others (as

be more innovative than

is

thus

in turn, that certain

The

also apparent in Table 4).

with additional

have not been confirmed

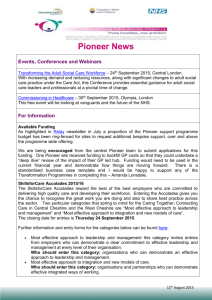

T.hle4

This suggests,

costs,

reducing the

banks tend to

findings,

however,

studies,

Percema<4ec£the.ddiM,Yalu^^

ji^e^sitein^Shlhe^^^

Markets

in

wluch bank pioneers the

Number

an

of

Average

share as

Numhcr

A>erage share as

of

products

follower

pioneer

(%)

imitated

(%)

innov ated

Boston

Morgan

Goldman Sachs

Slicarson Lehman

Stanley

Memll Lynch

Smith Barney

ofTers

products

Salomon Brothers

First

which bank

in

imitative product

product

Investment hank

Markets

Hams

Blyth Eastman Dillon

47.8

16

7

6

54.4

12

187

168

18 3

45,3

12

5

35.5

10

12.4

4

47.3

15

15 8

4

3

37.4

12

23.0

54.7

2

2

2

61.6

Drcxcl Burnham

1

Bear Stearns

Shcarson Locb Rliodes

1

1.4

42 9

1

15.1

69.2

7

3

4.5

11.7

62.2

0.6

1

1

154

47.9

Mean

\,i7a^,

luiaiiu (1989)

om Tufano

Taken from

Smdying innovation

should be enlightening

in

of

services from .he perspective

tlte

pioneering literature

se.ice oriemed,

As economies become more

the

R&D

fttnct.on

within service firms emerges.

Practitioners should benefit fi"om guidelines that can help to

determine expected returns fi'om products entering markets

at different

stages of market

evolution

Moreover, the need to explore these issues

particularly interesting in services

is

because there are possibly important differences between services and consumer or

industrial products.

These differences occur along many dimensions.

products are bundles of physical

objects

and intangible attributes

however, have a high degree of intangibility. This makes

it

For example,

Many

difficult to assess

all

services,

the needs of

the customer before creating a product and to measure objectively the satisfaction derived

from purchasing a service (Bitran and Lojo, 1993)

This thereby adds complexity to the

design and testing of services, thus increasing the risk associated with

1987)

development (Anderson,

moment of

are generated, they are

Moreover, some services must be delivered

accommodation, health

consumed

many

at

once

care,

The

and the

like.

When

such services

o^ producing and consuming the

act

cases, simultaneously,

and such services cannot be

product occurs, therefore,

in

inventoried for later use

Although the assets necessary to generate a

ser\'ice can,

course, be kept ready to deliver, the product per se cannot be delivered except

(thus,

yesterday's

the

at

For instance, customers must be present to receive services

their inception

like transportation, hotel

new product

unused hotel room or

airline

seat

is

lost

forever and

in real

of

time

cannot be

inventoried for later usage).

It

is

customer as

to

humans

this reason,

also salient that

their

many

services have to be delivered by humans, have the

primary input, or both

Patients are the

each delivery

is,

Health care, for example,

is

delivered by

humans

"raw material" of very complex production processes

by definition,

different.

For

As Bitran and Hoetch (1990: 89)

some

note, in

specifications-,

sei^ices

"i.

is

to

quality simply as •ccnfomiance

no. sufficien. .0 define

cannot be completely specified."

because the human encounter

Finally,

impossible').

(although, of course, no.

protect

difficult to

products or processes are very

newly created service

attribute this lack of

Bitran and Lojo (1993)

nature of services.

appropriability to the imangible

necessarily imply a difference

These differences do no,

of innovation

are

in all

The phenomenon of

innovation.

In financial services

dynamics of innovation:

highly relevant to the

a vety

envtronmen. and, most .mponan.ly,

(1992), for ms.ance,

creation

of many new

the

prices

advances

ulobalization

in financial

augmemed

changes

creatton of

new

argue that

m

m

Marshall and

weak appropnabUi.y regime

contributed to the

environmental factors have

environmental

volattli.y are:

^

^ong

technological advances,

of markets, regulatory changes,

in the speed, frequency,

schemes

regard, Tufano (.989)

,s

Pctruz,.,.

2

an incensing

to

For instance, the

variations requires the

and magnitude of price

manage

reporis, for a

in.crcs, inTlic poss,bi,i,i«s

the associated risk

This results

monopoly allowed

sample of 58 innovations

orpa.»n„6 nnancial

Del Vallc. and '"<"»"«''««'.

compiled a paniai

Finned) (1988). for instance,

seventies nnd 1988

the factors

frequem and abrupt changes

in

iisi

„,„„

oi mti

,„„

in a

more

to innovators.

the secunties

year after the ptoneer in

the market less than one

industry, that nvals enter

iThcrc

on

two parameters are

particular,

and Bausal, 1992,

theo^^ and others (Marshall

financial

that take

to the

increased volatility with respect

reduced duration of the transient

rapid dhftsion and a

In this

some parameters

the last 20 years

financal tnst^men.s durtng

responsible for such mcrease

,„

motivations and related mechanisms,

nature that have

mdus.ries, events of s.milar

1992)

different values (Geoffron,

Bausal

,ts

fundamental nature

in the

60%

innovations. See for

of the

e.a.ple

,„„„„ems created bcnvecn

,h= early

cases.

The mean number of

deals the pioneer

is

able to close before rivals enter

is in all

cases less than two.

The feebleness of

First, little

protection

in

from several causes.

the form of copyright or trade secret laws.

example, very few patents have been awarded for

Lynch was awarded a patent

Merrill

company was

allowed either

is

financial services, for

When

appropriabiiity regimes in services stems

able to obtain

for

Patents are awarded to tangible things

products.

Cash Management Account, the

its

on the grounds that

it

new

In

it

was

a novel

In financial services patents

computer program.

may

only be given to

-i

systems (for example, mechanical or electronic systems) that make the product

different or that serve to operate

In these

it

weak

appropriabiiity regimes,

somehow

new

services

are copied and improved after very short periods of time (Bitran and Lojo, 1993).

case of financial services

(SEC)

many

in

cases

the United States, the Securities and

in

forces

"inventors"

products they create (Tufano, 1989)

created and marketed everv' year.

is

In spite

As

have occurred

in

changes

cards), process innovations

EFTs

(ATMs

this,

numerous

..the

word revolution

in financial institutions

and instruments

financial

-automated

"

teller

new

machines,

CMA

-electronic fijnd transferring) and financial strategies

-cash

which implies the commitment of

development process,

Anderson and

is

a great deal

-leveraged

In this regard,

1989)

This

is

Clearly

of resources into the

undertaken as a profit-maximizing activity (Tufano,

Harris, 1986).

credit

management

(LBOs

financial products requires large financial outlays (Tufano,

financial innovation,

securities (zero

instruments (debit cards,

buyouts, swaps, corporate restructuring) (Finnerty, 1988, Miller, 1986)

developing

the

financial instruments are

These innovations include

the past twenty years."

coupon bonds, junk bonds), consumer-type

accounts,

of

Exchange Commission

information about

detailed

Miller (1986:459) indicates:

entirely appropriate for describing the

that

disclose

to

In the

1989,

carried out despite imitators needing to invest only a

and to

replicate a financial product

original investment to

fracion' of the innovator's

in the ntarket,

product

,„e

some

As a

law.

about infringing any paten,

wooing

cycles ,n

many

in

|<,89),

life

not

as

types of financial services,

This

is

especally

of secudties (Tufano,

for the case

we saw

many sendees

result, in

some, ephemeral.

industries are shc«, and in

sell .t

development cycles must be

almost instantaneously and

where products are copied

(Quinn, 1992).

reduced to the order of months

Levin

(1987)

al

et

competi.,ve advantages of

mechanisms firms use

argue

new

that

allernafve

use

firms

means

and products

or .mproved processes

,0 appropriate the returns

of mnova.ive

They

activities:

the

protect

to

1)

identify six

patents to

ume, 5)

tncome, 3) secrecy, 4) lead

patents to secure royalty

prevent duplication, 2)

moving quickly down

sales or service efforts

the learning curve, and 6)

effecve as a means of

Patents are not very

few industries

As Von Hippel(19S8 47)

: c lud ng

The patem

L tato"

grant

is

pro.ecng innovations except

indicates:

and/o! capturtng royalty

mcome The ans-r

no, useft.1 for either purpose

m

industnes

instance,

pha^aceuttcal industries but

in

patents

are

pari.culariy

ineffective or not

more

un.formly found

most mdustnes

patems do appear ,0 offer

Thou..h uenerally ineffect.ve,

For

very

in

some

effective

effect.ve than

,n

protection in ceriain

the

some

chemical

and

other alternat.ves

telecommunication industries.

the electronics and the

to offer

Similarly, secrecy appears

little

pro.econ

know-how trading among

repons the extstence of informal

325%

10

50%. Tufano 1990

to innovators

Von

Hippel

specialists ,n a given discipline

These

specialists

might find

economically reasonable to trade information that could be

it

considered proprietary, even with

Given the

(Von

rivals

of some forms of appropriation

relative inefficiency

firms probably utilize a combination of

That

effective.

on

depending

is,

appropriation methods

likely to

is

Hippel, 1988).

means of appropriation

the

industry,

methods.

ineff'ective.

Moreover, products, once released, are

(1993) report

financial

services,

In the financial ser\'ices industry,

In order to

inefficiency

of some

and

secrecy

are

nonexistent

relatively easy to imitate.

or

Bitran et

al.

ready by the time the

first

plausible alternative

one

way

is

institution introduces a

to assess the strengths and

it

is

in

type of

weaknesses of the

the service industry in terms of

new

important to have the next service almost

introduced.

to protect and derive rents

to introduce products that are hard to

new

very quickly, but often introduce an improved

be a leader

product introduction, therefore,

et al

patents

whenever an

it

some time

service since they have

original service

Bitran

be cost-

likely to

that:

account, others not only copy

A

relative

is

contexts,

be balanced with a greater emphasis placed on other

alternative

In

the

that

in certain

copy

This

is

difficult in

(1993) indicate, because products are not

from innovative

some

intrinsically

activity

is

financial services, as

complex

The process

of creation may be complex, involving high doses of creativity and the participation of

specialists

from

different areas, but replication

replicating a financial product

Even products

may

render them a

bit

is

is

easy.

on the order of 50% to

Tufano estimates

75%

Morone and Berg (1993)

difficult to replicate are

indicate,

"...

of

less than the innovator.

that require intricate technological or institutional

more

that the cost

networking that

not necessarily difficult to copy.

As

the relative benefits of pioneering versus fast

following are particularly open to question since information technology can often be

quickly copied, and later entrants often enjoy the benefits of lower-cost hardware."

Hence, adding complexity to products through a more intensive use of information

technology or other means

competitors'

will

movement down

Given

this,

we would

not necessarily cause delays in product difHision or in

the learning curve.

expect

that, at least in financial services,

be an important form of appropriation

if

not the dominant

protection and secrecy are ineffective and, for

down

If patent-related

and moving

practical purposes, absent,

the learning curve occurs almost instantaneously because of the relative simplicity of

the products, then lead time (being

new products

No

in financial

services

that,

related to order

in

at

consumer markets.

general, market share

is

For these types of products

a)

The dynamics of order of

entry

new

disregarding the characteristics of firms that launch the

The

are

a

has been

literature

sometimes

national distribution" (e.g..

by national advertising

Urban

(e.g.,

is

products.

et al.,

in

evaluated

Thus, whether

in

the

firm's

seldom studied.

identifies as first entrant a

product that

first

"achieves

1986) or requires that the product be supported

Whitten, 1979)

advertising or national distribution

of entry,

number of

sometimes

because they lack strategic relation with other products

portfolio, or for other reasons not related to order

b)

in

in\ersely (though not necessarily lineariy)

on pioneering advantages does, however, contain

literature

fail

it

saw,

of market entry

problematic aspects

products

we

on pioneering advantages has primarily concentrated, as

packaged goods aimed

The

to market) and a quick response in introducing

study, however, aside from Tufano's, has looked into this problem in depth

literature

determined

first

might be the most effective methods of appropriating the returns of

innovation efforts

The

all

one.

pioneering should

"Hence,

a national market,

11

if

it

a firm does not have national

does not qualify as an entrant.

(Robinson, Kalyanaram and Urban, 1994:2). This might be problematic because indirectly

it

means

that the product that qualifies as an entrant has

an important

set

of complementary assets

thus precluding

distribute),

methodology one runs

(i.e.,

been launched by a firm that has

being able to nationally advertise or

many products launched by

smaller firms.

By

the risk of confounding "entry" with financial muscle.

using this

The method

also censors entrants that have failed to stay in the market, thus overstating the effect of

entry on the survivors.

c) Units

of analysis tend to vary.

while others analyze organizations

Some

Making

studies center their attention

on products

generalizations from the literature as a whole

is difficult.

d) Censoring:

Many

studies cannot or

do not consider the products'

entire historv',

thus overestimating or underestimating pioneering.

e)

A

rapidly changing market

subsequent entrants

in

a

ver\'

may

defy order of

entr>'

dominance, especially

if

environment are able to incorporate into their

volatile

products characteristics that take such changes into account

f)

Finally,

premature market conditions

obscure the effect of order of entry

fijture

Pioneers

consumers or creating network

others to invade

As

may end up

have died

in

may

also

bearing the weight of educating

externalities yet unconsciously level the field for

though empirical

Some of

this

results

controversy

appear strong, empirical generalization

show

for a variety

their youth.

of products

Colder and

specified scale of commercialization and

is

discussed by Colder and Tellis (1993) who,

is

using an historical approach, argue that moving

contrary, they

pioneering "too early")

it.

a result,

controversial.

(i.e.,

first

that almost

Tellis

achieves no advantage.

all

of those

12

the

who have moved

first

to reach

any

do not require the pioneer

many of those pioneers do

On

not have a meaningfijl

share of the market

in

the long run.

information from articles

some

In their

as far back as 1842 to prove their point.

approach solves the problem of reverse causality

historical

being identified quasi-automatically as pioneers),

market

methodology, Colder and

that are not well

gather

Though

this

high market share firms

can also overlook other entries into the

documented.

Such aspects should be taken

study the phenomenon

it

(i.e.,

Tellis

when choosing an appropriate methodology

into account

to

in financial services.

Hypothesis

On

we

account of the aforementioned

hypothesize

first

mover advantages

for

financial services innovations:

H

There

of

is

a negative relationship

financial

services

between order of market entry and market share

innovations,

controlling

for

firm

size

and

product

interrelatedness.

This proposed relationship

been discovered

in

many consumer

products,

consumer packaged goods (Robinson,

Colder and

with the same empirical regularity that has

falls in line

et a!.,

in particular

the pharmaceutical industry and

1994), but runs contrary to the findings of

Tellis (1993).

13

Methods

The study

is

based primarily on historical analyses.

financial products are

Product histories for several

assembled and reconstructed using archival records.

These records

are information available in published sources of information (which include primarily

newspapers,

regulatory

institutions.

informants

in

and research papers) and from other sources such as

trade journals,

The

historic

information

is

then

launched

in

Costa Rica within the past 15 years.

lines (credit card, debit card,

sample

we

in

which product

sample of Costa Rican

we

and pension

fijnd)

A

is

is

a set

of

used

whose

in

Thus, through

three product

this

choice

This study

is

oi'

part

of commercial banks were reconstructed for

For the purposes of

financial institutions.

included only those products

done with the

line histories

financial services

sample of 36 entries

are trying to minimize the problem of lack of fine-grain data.

of a larger one

a

from

data

pertinent institutions and by others familiar with the industry.

For convenience of data gathering, the sample chosen

•"t

with

validated

histories

this paper,

were reconstructed

however,

This was

in detail.

intention of a) correctly identifying pioneers, b) avoiding censoring, and c)

choosing products which had been launched

potentially different market effects

in

roughly similar time-frames (to control for

when agglomerating

the sample).

The sample of products was circumscribed purposefully

to a small market

under

progressive deregulation, and, thus, historical information could be obtained to permit an

accurate determination of pioneering and subsequent entries.

which these products have flourished provided an

related innovation.

No more

Moreover, the

interesting case for studying service-

than 20 years ago, the commercial banking sector

Rica was a heavily protected and regulated domain.

domains of

activity

were allowed

14

to

in

Costa

Economic deregulation dramatically

changed the structure of the industry since 1980 and companies

specific

industr>' in

offer

new

that

services

were confined to

in

areas

that

had

traditionally

belonged to banks

offer a wider range

of products

AJI financial institutions

in

have been forced to renew and

order to remain competitive

and the development of new products

in

Over

15 years, innovation

the financial services industry have

become

increasingly important.

Our choice of sample

includes products that have been created

in

the near past.

This allows for a relatively simple process of information gathering from public records.

also

permits us to gather first-hand information from people

launching of the products

Another important advantage

dynamics of the dependent

product-lines

whose

variable,

is

that

we were

Thus,

within organizations

who may

not be entirely accurate.

able to assess the

Moreover,

we chose

comparison and contrast of

trying to avoid overreliance on single informants

overstate pioneering status, or

To avoid

participated in the

we were

market share, over time

history could be reconstructed through

several data sources.

who

It

whose

recollections might

these problems, multiple measures were collected both

from organizational informants and from secondary sources, allowing us to cross validate

and triangulate data from different origins (scholars, experts, journalists, etc

sources

who were

An

fact

not interested

in

be censoring the dependent variable, since

case the long term

Although

marketing

field,

may

sur\'ival

and

component

is little

has been widely used

Utterback

in their

is

plausible that not

that

we may

in

enough time has

In this

not yet be long enough.

particular interest are the studies

1992),

it

is

and performance of the different market entrants.

historical analysis

it

particularly

overstating the pioneering status of a particular firm.

important disadvantage with the chosen sample of products

elapsed for assessing the

),

(1994)

used

in

in

studies of pioneering carried out in the

studies of technological innovations.

Of

done by Cooper and Schendel (1976), David (1986,

AJI

these

work.

15

authors

incorporate

a

strong

historical

The dependent

variable in this study will be total market share

of the nth entrant

at

the time of the study, measured as percentage of total customers using a particular

financial

instrument

committed

and

reports

archival

A

periodicals.

financial,

Data sources for

to the financial instrument.

Archival

data.

manual search of

all

of

percentage

as

alternatively,

and,

total

of dollars

portfolio

this variable included informants'

were obtained primarily from

data

the issues of the four

most important

financial

local business,

and economic journals since 1985 (and a selective search of some older issues)

was coupled

to both electronic and

newspapers.

We

libraries, the

manual searches of the countries' most important

also searched several libraries in the country (for

Central

Bank

Librar>', the library

example

universities'

of the Stock Exchange Commission, and

several others) for sources of information which included books, unpublished theses and

papers, and

monographs

In

all

we were

able to assemble over 100 articles or printed

pieces of information which referenced the product lines under scrutiny

was

This information

validated with data provided by organizational level informants and three industry

For

experts.

pension

funds

Commission which required

portfolio

size,

information

we

all

we

contacted

pension

fijnd

number of customers, and

an

incipient

operators

the

like

in

Pension

Fund

Regulatory'

the country to report data

When we

on

found contradictory

either sought a third piece of confirmatory evidence or asked an industry

expert for clarification.

Because the products were recent, confirmatory evidence was

generally found with only a moderate degree of difficulty.

operationalized

as

the

Pioneers are

entry will be used as an independent variable.

The order of market

first

entrant.

Time of

entry

informants.

Most organizations had personnel who were

of entry of

their product.

was obtained using

able accurately to recall the time

This was confirmed with archival data and,

16

primarily

in

the case of

pension funds, with the date reported to the Pension Fund Regulatory Commission as the

first

year of operation

An

additional independent variable will be the elapsed time delay since the

The

entry until the nth entry.

rationale here

is

that the impact

vary depending on the time elapsed since the

we had

determined once

The

of being the nth entrant

entry.

first

first

will

Elapsed time was easily

dates of product introduction per institution.

institution's size, in terms

of

total

Number of employees

study, will be used as a control variable.

These

correlated with total assets

size

number of employees

measures are

leverage existing resources to support a product

reputation, and distribution channels

in

a

is

at

the time of the

highly and positively

proxy for the bank's

ability to

terms of advertising expenditures,

This information

was obtained through informants

within the organizations

rest

of the institution's products can also have a moderating

variable

People may be inclined to switch to certain institution's

Relatedness with the

effect

upon the outcome

products because of the added convenience of carrying on

organization

For

this

businesses with

purpose a measure of strategic focusing was used

of the point cloud on the client-product matrix of each

of product interrelatedness

may be

all

Institutions with larger/ampler arrays

better positioned to leverage

which quantified the change

institution

in the

new product

offerings'*

The dispersion

was used

as a

measure

of products and

An

one

clients

alternative measure,

dispersion of each bank's product cloud,

was

also used

as a measure of interrelatedness (small values indicating small departures fi"om current

product offerings).

Finally, a

dummy

hypothesized relationship.

variable

This

was used

for assessing the regulatory effect

dummy was

•Please sec Appendi.v 4 for details.

17

upon

the

assessed with the help of three industry

experts

who were

independently asked which of the product lines was influenced by

regulation (when operation required permission from the regulator, or

only permitted certain institutions to operate

The model

to be tested can be

a2

^nc

'

as:

a3 ^

^nc

nc

the regulator

the time of entry).

summarized

ai

^

^nc

•fe

at

when

a^

ctA

'^nc

'-•tie

!

where,

Snc = market share of the nth entrant

in

Enc" ^ Order of entr>' of nth product

Tnc "=Elapsed time

category

in

c, in

category

percent

c.

delay between nth entry and the

first

=Re!ative size of institution that released the nth product

Anc

as a ratio of total employees with respect to largest entrant

Rnc

Gpc

entry in category

"

in

for

^Regulatory variable (dummy

variable,

18

(measured

in

category

c.

dichotomous).

Following a section of exploratory data analysis,

regression models.

category' c

months.

category).

bank releasing product n

=Index of product relatedness

in

c, in

we

will

fit

a

taxonomy of

Results

Qualitative Analysis

In general,

ail

products examined here present different patterns of entry,

seemingly different relationships between order of entry and performance.

exit,

and

For some

products, particularly those which only add features or are exclusively driven by changes

the effect of pioneering

in regulation,

upon performance seems

strategic products that enter the market in the absence

expected

negative

relationship

between

order

to be small.

However,

of regulation reveal an apparent

of market

entry

and

measures

of

performance.

Pension Funds.

Pension funds

in

this

market had traditionally been administered by the

Economically active people contributed a fixed percentage of

fund.

In such environments,

their salaries to a national

private pension fijnds tend to be successful

operated pension system gives small pensions

at

high retirement ages.

customers would have an incentive to transfer to

Problems with the state-administered

fijnd

fijnds

that

opened an opportunity

offer

In

if

the state-

such a case,

more

until July

of 1995.

benefits.

for other institutions to

enter the market and offer complementary pensions This industry operated with

no supervision

state.

little

In fact, before that time, private pension funds

or

could

not operate openly as such, but only as providers of additional coverage to that given by

the state.

Even

of 1988.

In

so, the first private

pension

fiind

operator entered the market

in

August

1995 the funds were authorized to operate as such and also received an

19

additional impulse

in

the form of a tax break'.

between 1991 and September of 1996. Table

number of clients, and

Table 5

-i

5

Ten more operators entered the market

summarizes the order of market entry, the

the size of the portfolio for the last three years.

% of market

When

share

is

measured

in

terms of portfolio size (not shown on graph), the

pioneer also appears to retain an important portion of the market.

%

of

market

(Sept 96 as

total

%

of

customers)

2.5

Order

Figure

2:

Order of market

measured as

% of total

7.5

5.0

entrN' vs.

of

10.0

Market Entry

market share for pension funds

1996

customers as of Sept

Market share

Figure 3 shows a longitudinal history of total market shares (measured as

total

customers) for

in this

all

market for a

participants

total

The pioneer

of 23 months

in this

According

first

pension funds entrant gained a

maximum market

50%

of the pioneer's

share.

%

of

market was able to operate alone

Firms' market shares start leveling off after

approximately 4 years since the

entry.

is

.

to these

graphs and data, an early

share over time that

In this case, not considering the

is

approximately

one apparently atypical data

point (PF6), firms that entered the market within an elapsed time delay between 27 and 57

21

months eventually averaged 57% of the

pioneer's share.

Very

stabilized with market shares that represent approximately

(8%

share

appear to have

late entrants

5%

to

10% of

the pioneer's

in this case).

Order of entry

vs. marltet

share for pension funds

Entrant

10CW.

•-

90%

-

80%

-

70%

-

—V

60%

-

I

50%

—

—

-•

ia

-o

2nd

-—

-—

m\

3fd

-

-'

V

5»i

—

-a

30%

•

OT*

•

10%

-

-•

-

0% o-

—

em

7th

8th

S=^

92

93

Year

Figure

3

Order of market entry vs market share

for pension funds.

Other factors, however, particularly organizational

effect

upon market share

size,

seem

Figure 4 shows a scatterplot of order of

to have an important

entr>' vs.

percentage of

the pioneer's market share (measured as the relative size of its portfolio vs that of the total

market).

same

1996.

The squares

for the year

Symbol

represent this percentage for the year of 1994, the triangles say the

of 1995, and the

size

is

circles represent this percentage at the

an indication of organizational size (the larger the symbol, the larger

the size of the institution measured

in

total

scatter plot reveals an apparent influence

market shares.

end of August of

Notice that entrant number

of

number of employees)

size

five,

22

Inspection of this

upon the dynamics of an incumbent's

which

is

also the largest as

measured by

symbol

size, increases its

combining the pension

offer

market share noticeably

fiind business

also banks, but

8,

three years, signaling the possibility of

with a larger platform of products, thus being able to

more complete product packages

entrants 7 and

in

it

is

exclusively operates this pension fijnd) or

A

to customers.

similar effect

not observed in entrant

is

number

observed

three (which

number four (an insurance company). Size may

also signal a greater ability to leverage sales efforts and achieve scale effects.

relationship

to

between SIZE and market share

is

positive and significant for the years

The

1994

S-r=0 70, p<0 05, for 1995 S-r=0.63, p<0.1, for 1994 S-r=0 61,

1996 (for 1996:

p<0

1).

Entry vs

%of

pioneer's share 1996

1.2

Variables

"o ol pioneer'*:

PFl

share

O

9

PV(,

0.9

Entry vs.

^

Entry vs.

E

Entry vs.

%of

%of

%of

pioneer's share

1

pioneer's share

1

pioneer's share

1

PF2

PK5

6

0.5_

in

"P

J

-

PF7

0.2PF4

O

PF8

e

PF9

10

0.0

Order of entry

Figure 4 Order of market entry vs pioneer's share for three years

23

P ension funds

996

995

994

Table 6 shows a matrix of Spearman-rank correlation coefficients for order of

market entry and market share measured as a fraction of the pioneer's share

total

customers) for the years ended

in

(in

terms of

December of 994, December of 995, and August

1

1

1996.

Tabic

6:

ENTRY and the

Spcarman-rank correlations between the variable

\anablcs SIZE and market share for \anous \ears (Market share measured

as

% of the pioneer's share m terms of total customers)

Pension

Spearman-rank correlation

Variable

SIZE

-034

MARKET SHARE:

%PION%

-0.72*

%PION95

%PION94

-0

81**

-0

80**

fiinds.

coefficient.

**p<{).()l.*p<().()5

As expected,

a negative relationship

between order of entry and market

strong and statistically significant throughout

(only last three years shown).

these years the relationship conserves the expected direction, but

decrease (from 0.8 to

upon the outcome

relationship

72),

presumably because other variables

between order of market entry and SIZE.

ones) are not, according to these data, the

pioneers

fijnds

But these advantages

associated with

some

first

seem

are,

ones or the

fairly

Throughout

coefficient starts to

start exerting influence

Table 6 also suggests that there

variable market share

These data on pension

its

is

is

no

significant

Larger institutions (or smaller

last

ones to enter the market.

to indicate that there are

some rewards

for the

however, quickly overcome by other factors

organizational characteristics of subsequent entrants.

24

Later entrants

into this financial

market are not delayed by any

sort

of proprietary considerations, hence

the pioneer enjoys only a relatively short period to operate as a monopolist.

Debit Cards

Debit cards were recently introduced into the financial system under study.

payment instrument requires the cardholder

to

have a checking account with the issuing

institution, with the debit card ser\'ing to automatically

from the checking account

businesses.

The product

and electronically deduct payments

requires a fairly extensive network of affiliated

Moreover, debit cards become more

useflil

if

they can also be utilized to

obtain cash from automated teller machines or from bank offices

would expect

Hence, a

priori,

large banks, or banks with extensive geographical coverage to be

successfijl in this market.

Table 7

Raw

data for debit card industry

Tot. assets.

Operator

DCl

This

Dale of

Order of

Customers as

12/95

entr>

entr\

of 10-96

(mu)'

# employees

one

more

The

debit card entered the market being studied in

first

additional operators had entered the market by 1996 and another

enter soon.

The above data

commercial banks.

between the pioneer and the next two entrants

caused by regulatory changes that allowed

made

it

Six

two were planning

Table 7 summarizes some characteristics of these operators.

institutions are

This change

August of 1987.

to

All debit card

reveal a fairly short elapsed time

A wave

of new entrants occurs

in

1996,

banks to provide regular checking accounts.

all

unnecessary for banks to circumvent

this regulatory constraint,

which

they often did, through alternative and more creative means.

Figure 5

total

is

a scatterpiot that

market share measured as

industry' at

%

the time of the study

shows order of market

of customers for

all

entr>'

versus percentage of

participants in the debit card

Inspection of this scatterpiot doesn't suggest the

presence of a negative relationship between order of market entry and long term market

share

The pioneer

doesn't have any significant advantage.

able to capture market share

one

sixth

The

It

is

the third entrant

pioneer's market share, in this case,

of the third entrant's market share

A

is

who

is

approximately

very late entrant (with a total elapsed time

of 106 months after the pioneer's entry) appears to capture approximately 50 percent of

the pioneer's share in a relatively short period of time.

26

60

4

2

80

Order of market entry

Figures

datapoinis

No

Order of market entry

is

vs.

market share For debit cards

longitudinal

data could be obtained for this product

notwithstanding, an examination, even a cursory one,

factors

may be

inferred

that additional factors

of the

institution,

data pomt

The

size

of the

an indication of the relative size of the institution.

It

might be that

this

is in

much

determined by number of employees,

minimum

technological platform

is

In Figure 5 the size

represented by the size of the

is

Obviously, the very large institutions entered

suggesting that a

shorter life-cycle, and

of pioneering.

effect

this

market

in isolation

As

must be kept by the customer with the issuing operator.

drive customers to adopt one or the other debit card,

overcome the

effect

of eariy entry

number of ATMs each incumbent

first,

perhaps

necessary for firms to enter into this

market because convenience to the customer drives the adoption of

Moreover, the product cannot be adopted

This

particular.

order so that the effect of other

product has a

have already overcome the

in

a

minimum,

a

this

product.

checking account

Convenience, however,

and

this

factor

may

may

quickly

Figure 6 shows, through the size of the data point, the

has.

Entrant number three holds the largest

27

number of

followed by entrant number five with

those by

far,

nearly as

many

as entrant

5.

Though

60%

as many.

this relationship evidently

the cross-sectional information at hand, there

is

Entrants

1

and 2 have

cannot be established with

apparently a positive correlation between

market share growth rates and # of ATMs.

Market

sluirc (as

%

of pioneers).

4

2

6

Order of market entry

Figure 6

Order of market entry and market share

The

debit cards.

size

of the data point

is

as

% of pioneer's market share for

an indication of the number of ATMs each

participant has

The

entry.

entries

effect

of

entPy'

may

also be influenced

The absolute order of market

entry could hide nearly simultaneous entries or

which are separated by long periods of

market share

at

by the time elapsed since the pioneer's

time.

In Figure 7

we

have plotted

the time of the study against elapsed time since the pioneer's entry.

groups can be cleariy recognized

in

the graph.

One group of

Two

eariy entrants introduced

debit cards into the market within a total elapsed time of 17 months.

28

total

The next entry

occurred 58 months

and more than eight years

later,

after the pioneer's entry

we

can

observe a second group of institutions entering the market.

0,8

Market

sliarc.

-,

1996

•1.

85

50

15.0

120

Elapsed months since pioneer entered

Figure

7:

Elapsed time since pioneer's entry vs

Two

observations are

inconveniences of utilizing

in

order

First,

total

the data on debit cards indicate the potential

order of market

strict

might be preferable to moderate

this strict

market share for debit cards

entry' as

Alternatively, time elapsed since

independent variable.

Second,

different institutions entering a

strategic while the later

wave of

first

entry could be used as an

can see that different motivations

market

In this case, early entrants

entrants

It

order by coding entries as early entries, early

followers, and so on

we

an independent variable.

may

chan^e.

29

just

may

may

stand behind

well be termed as

be taking advantage of a regulatory

Despite

this,

we do

significant relationship

8

observe for the case of debit card introduction a

between order of market entry and long term market share

shows a matrix of Spearman-rank

correlation

coefficients

interest.

We

indicative

of total number of customers), the two variables

total

%PION_SHR

number of employees),

total

and

%

Notice that market share (as a

that

the

time elapsed since

for

is

measure

SIZE! and -0.96 with p<0 001

between market share and number of

for

The observed

SIZE2).

ATMs

is

come

ATMs)

positive

relationship

p<O.OI.

Though

between order of market entry and

may

models

give an incorrect picture of the

though

in this

case no firm conclusion can be drawn, that

into play that eventually dilute the pioneering effect.

case of debit cards

network of

-0 86, p<0.01

observation.

Finally, the data suggest,

other factors

negatively

also important to note that examination of statistical

alone, without further expIorator>' data analysis,

phenomenon under

=

S-r

statistically significant at

the table generally supports a negative relationship

is

and

are using ranks, with

negatively correlated with both measures of entrant size:

it

is

terms of

ELAPSED

is

of

In this case the large established players entered first (time

first entr\')

long term market share,

(which

size (in

of the pioneer's share)

we

Table

variables

CLIENTS

variables

correlated with order of market entr>' (and similarly, given that

elapsed

for several

have included for reference purposes the variable

and

assets

statistically

we

observe that entrants with larger coverage

are apparently able to

data also suggest that, for this product, a

grow much more

much

30

In this particular

(in

the form of a

rapidly than pioneers.

shorter transient

monopoly

The

existed than

for pension funds.

Three firms entered the market within a period of 17 months.

second wave of entry, presumably driven by changes

months

after.

are less than

Table 8

in

regulatory conditions, occurred 58

Nonetheless, very late entrants appear to stabilize with market shares which

8%

of total.

Spearman-rank correlation coefficients for variables of interest.

Debit cards

A

all

banks

in

1979

in

the United States offered a credit card plan (Federal Reserve Bulletin, 1973),

71%

(Mandell,

of all banks had

(BankAmericard

shown

in

By 1976

1990).

Figure

(later

8.

and

credit card plans;

there were

VISA) and Master

in

1985 the figure had grown to

two dominant organizations

Card).

Notice that explosive growth

The growth of

in

90%

the business

their total

accounts

is

starts after 1975.

r^f^.r^r-^r-^rv.'^*''*-'''^ CO GO ^

CO

co

aa

^ <c as o^ oi o>

O^O^a^C^o^o^<T'O^C^tcT>0^0^<x>o^CTlcno^O^O^O^O^CTlCTl

oo

fv.

Figure

8:

Groulh of Credit Card accounts

in

the

US (VISA and Master

Card)

Taken from

Krumme. 1987

The

first

credit card plan in the financial system

by a commercial bank

(this is a relatively early

second entrant appeared

advantages

in

may have been

the market after 108

obtained

in

under study was created

entrance even by U.

months

In this

S.

in

1976

standards).

The

environment pioneering

terms of network externalities

Card operators

derive income from customer's interest payments and also from the commisions paid by

vendors, thereby making

it

crucial to develop a large

network of

affiliated businesses.

Figure 9 displays a scatterplot of total credit card market share for three years (1993,

1994, and 1995) versus total elapsed time since the

32

first entry.

As shown,

the very early

first

entry doesn't sustain an above average market share over time.

(108 months

after) captures

In this case

is

it

approximately

45%

of the market and retains

is

having any important

appears that large institutions (as indicated by symbol size) enter

In

relationship

it

entrant

consistently.

not apparent that size of the institution or the plausible combination of this

product with a more ample product platform

entry

The second

effect.

in a

Moreover,

it

second wave of

however, the observed scatterplot seems to support a negative

general,

between order of market entry and market

05

share.

Variables

•

A

ElDSdtotvs mi<t%95

ElDSOtotvs mkt%94

ElpsStotvs mkl%93

0.4

02

1

-0

V-

-

1

25

-50

100

175

250

Elapsed months since pioneer's cntp.

Figure 9

months since the pioneer's entry versus market share

of total customers.

Market share measured as

Elapsed

credit cards

total

time

in

for

%

Figure 9 reports total market shares for the credit card market and Figure 10

market shares measured as a percentage of the pioneer's share

percentage of total customers).

(in

both cases as

Notwithstanding that the pioneer had a period of

approximately seven years operating as a monopolist,

33

it

fails

to reap long

term market

share advantages.

In this case the

second entrant became (and stayed) the market leader

After this period another three competitors entered the market during a three-year period.

Credit card marl^et shares

Figure

Market shares

10;

Notice also

increases

This

is

may

its

in

for credit cards

Figure

1

1,

that the pioneer retains the

number of customers somewhat

reflect different strategic intentions

growing

overall.

of the

from other incumbents but rather from the

any type

and

in

the early entrants' total

third entrants into this

customers they

This

may

intrinsic

grow without

taking market share

growth of the market, perhaps

explain in part the absence of erosion of

1

market do exhibit consistent growth

34

Moreover, the market

different firms.

number of customers. Figure

attract.

(in fact

consistently) despite losing market share.

This means that later entrants can

attacking different market segments.

number of customers

1

shows

in

that the

the total

second

number of

^}

Figure

first

1

number of customers

shown

Total

1

four entrants

for participants in Credit

Card business

Only

Table 9 displays Spearman-rank correlation coefficients for several variables of

interest.

Notice, as observed

elapsed time since

first

in

the scatterplots, the strong negative relationship

entry and market share

in

the credit card business

negative relationship between order of entry and market share

statistically

significant throughout, the coefficient

coefficients

of -0.94, -0.90, and -0 69, p<0.001).

negative relationship between size (measured by

0.69,

p<0

001).

As observed when

later in this case.

Finally,

market share for

diflferent

Though

becomes smaller

Notice also the

There

between

is

also a

this relationship is

as time passes (S-r

statistically significant

number of employees) and entry

(S-r

=

-

exploring the scatterplots, large firms seem to enter

one can observe

a positive relationship

between

all

measures of

years but, again, the sizes of the coefficients diminish.

could signal that the early entrants' market shares are starting to erode.

35

This

Tabic

9:

related to

Spcarman-rank correlation coefficients for \anables

Our

goal

in this part

of the paper

for the dependent performance variable

of the

institution's total

is

to build a sensible and eflficient baseline

SHARE,

exist

controlling for institution size, the effect

product offerings, and the effects of regulation.

construct a model to include question predictors

model

ENTRY

and

We

will

ELAPSED. Should

then

a link

between the question predictors and product performance, controlling for the

aforementioned

accordingly or,

effects, practitioners

at least, qualify their

could then design their product launching initiatives

perceptions about possible performance outcomes of

financial products.

First,

are

shown

Table 10

in

the

raw data

Table

set

and the distributions of

all

variables

were examined

These

10.

Descriptive statistics for selected variables

Normaiit> of

distribution C^)

Variable

SHARE

Mean

s

d

Min

Max.

this to the large

average elapsed time since

entry (125.4 months),

first

we

can infer a

possible negative relationship between elapsed time and share.

The average

size

of the

institutions

Given

institution in that product category.

influence on the

outcome

variable

is

SHARE.

approximately

this,

it

is

27%

the size of the largest

plausible that size will exert

Such presumption

is

some

reinforced with non-

normalities observed for this variable.

In general, the non-normalities

comparison

of

coefficients

for

Pearson

the

observed signal the presence of curvilinearity.

correlation

variables

at

issue

relationships which included the variables

announcing the need for transformations.

Tabic

1

with

coefficients

rendered

large

SIZE and

Spearman-rank

differences

SHARE

(as

for

shown

A

correlation

all

in

bivariate

Table

11),

positive relationship between order of market entry and elapsed time.

This relationship

not a straight hne because of the different product categories present

Second,

we

sample (though

it

is

Third, there appears to be a clear negative and curvilinear relationship

ENTRY

INNOV

appears to indicate a strong negative relationship between the two

at

various markets,

i

e.,

more innovative

in this

regard) tend to enter

This graph, however, does contain a few seemingly atypical data points

the scatterplot of order of entry

real

between

ELAPSED

time.

(ENTRY)

ELAPSED

the graph of

consider

when

our

This could indicate that those firms which have wider product platforms (more

products aimed

earlier,

in

between

Fourth, inspection of the scatterplot of

order of market entry and market share.

variables

not clear whether such entries are prototypical

This clearly indicates the need to control for size

for certain product categories)

versus

the sample.

can see that a group of notably larger institutions appear to have entered

relatively early in the

analyses

in

is

A

and

vs

similar thing

INNOV

vs.

SIZE suggests

SIZE suggests

happens when

that

we

Fifth,

first.

although

that large firms tend to enter

this

look

must be qualified

at

if

we

the relationship extant

This suggests that different results could be obtained

using either variable as predictor, thus pointing to the need for differentiating any

implications

in

terms of order of entry and timeliness of entry.

39

Figure 12: Scatterplots for selected bivariate relationships

.

ENTRY vs ELAPSED

ENTRY

250

vs SIZE

2

1

• •'

SIZE

175

••

•

.••'

09:

•••

1000

•• ©••

.••

••

"it*.

§•

50 CL

00

00.

18

12

6

12

6

ENTRY

ENTRY

SHARE

ENTRY

SHARE

VS

INNOV

OS

ENTRY

VS

INNOV

80

<

06

• •

••A*

••••si

•

••«

02

0_?

fiS«e«**««««A«*»4

6

12

18

0„

25

ELAPSED

SIZE

1

25

12

J

ENTRY

ENTRY

EUPSED

INNOV

VS SIZE

2.

VS

INNOV

80

•

A

*

f

* •

•

40

03

•- •

20

>.•

Hi.

1000

175

250

25

100

ELAPSED

ELAPSED

40

175

250

As suggested by

transformations

on

the

results

variables

the

of the exploratory data

SHARE

transformations and the Rule of the Bulge,

We

perform best for these cases

Appendix

1).

and

we presumed

nevertheless tried

In fact, the natural log

Tukey's

ladder

that natural logarithms

several

possibilities

showed

that both sariables

Figure 13

Normal Probability

Normal

Plot of

will

analysis utilizing the

be designated here as

probability plots (coupled with

SHARE*

had attained normality, as indicated

probability plots for

SHARE*

SHARE*

in

Figure 13.

and SIZE

Normal Probability

15

15

Normal Distnbution

00

Normal Distnbution

41

^

Plot of

-80

00

were

Kolmogorov-Smirnov

00.

15

in

Various analyses were performed to assess the convenience

Normal

of such transformations

of

would

(shown

Bi-variate scatterplots confirmed that the selected transformations

adequate (see Appendix 2)

SHARE-

we performed

of both variables seems successfully to restore

transformed versions of the original variables (which

tests)

Using

Then we proceeded with our data

linearity in the relationship.

and SIZE*)

SIZE.

analysis,

SIZE*

A

comparison of Spearman-rank correlation coefficients and Pearson correlation

coefficients

Appendix

showed

Once comfortable with

3).

had been minimized (see

that the previously observed differences

the variables to analyze,

we developed

bivariate correlations, estimated through Pearson correlation coefficients

summarized

in

Table

12,

revealed that the dependent variable