Document 11044709

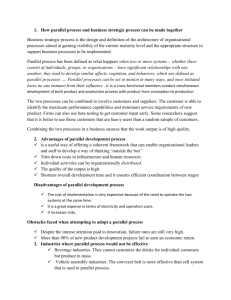

advertisement

HD28 ^414 DEWEY m Determinants of Organizational Innovation Capability: Development, Socialization, and Incentives by C. Annique Un WP#4148 December 2000 C. The paper is derived from my Annique Un, 2000 thesis at the Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The MIT-Japan Program Starr Foundation, the CS Holding Fellowship in International Business, and the Massachussets Institute of Technology Doctoral Fellowship provided funding for this study. I would like to thank the managers of the companies studied for sharing their experiences with me. The comments of participants at Technology Proseminar helped improve the paper. am also grateful to Eleanor Westney, Michael Beer, John Carroll, and Alvaro Cuervo-Cazurra for their comments and suggestions. All errors remain mine. the Massachusetts Institute of I APR 2 6 200^ LIBRARIES Determinants of Organizational Innovation Capability: Development, Socialization, and Incentives ABSTRACT This paper analyzes how companies develop the innovation capability by analyzing management practices that facilitate knowledge mobilization and From in-depth comparative case studies, this study proposes that cross- organizational factors and creation for innovation. functional communication frequency and overlapping knowledge knowledge influence this capability. While knowledge mobilization, overlapping communication frequency facilitates facilitates the creation process. Moreover, cross-functional how employees it proposes that a set of management managed, specifically selection, orientation, reward, and development, not only support this capability directly but also indirectly by generating cross-functional communication frequency and overlapping knowledge. The empirical tests using 182 innovation teams of 38 companies support these propositions. Specifically, cross-functional communication frequency and overlapping knowledge support a wide range of capability outcomes: product innovation, customer satisfaction with the innovation, efficiency, and speed-to-market of the innovation. For management practices, the results reveal that cross-functional development of professional employees is the key practice as it facilitates a wide range of outcomes of this capability: product innovation, customer satisfaction, efficiency, and speed-to-market of the innovation. Moreover, it indirectly supports this capability by facilitating both cross-functional communication frequency and the accumulation of cross-functional overlapping knowledge. The control over individuals" rewards divided between functional and non-functional managers, orientation, and team-based work patterns support cross-functional communication frequency, which facilitates knowledge mobilization. However, cross-fiinctional development not only provides the benefits of these practices, but also enables the acquisition of overlapping knowledge, which support the new knowledge creation process and thereby the overall innovation capability. practices relate to control over the reward, Key words: Knowledge work are pattern, Mobilization, New Knowledge Creation, and Management Practices. INTRODUCTION The innovation know how to develop capability it. for competitive advantage, is critical however, we still do not This capability has been discussed as "dynamic capability" (Teece, Pisano, and Shuen, 1997), "core capability" (Leonard-Barton, 1995), "combinative capability" (Kogut and Zander. 1992), "core competence" (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990), and "integrative capability" (Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967), and these authors consider However, despite the extensive debate about of "how" organizations develop it. As its importance, there Foss, Knudsen, and question of intentionality becomes particularly salient when it as key for competition. limited understanding is still Montgomery (1995) considering how indicate: "The a firm sets out to build a given set of capabilities. Because resources that support a competitive advantage are by definition inimitable, and unidentifiability to say how one should invest to build a is a sufficient condition for inimitability. competitive advantage. one cannot make such investments purposively this conundrum?" is On Is there a view way that out of (p. 13). personnel management practices that facilitate the In answering this question. I is, "What on the organization level of analysis are the factors and development of organizational innovation draw on the theoretical approaches of the resource- based theory of the firm (Penrose. 1959; Barney, 1991) and the innovation I is difficult the other hand, the not satisfactory either. Therefore, the overarching research question of this paper capability?" it literature that focuses (Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967; Nohria and Ghoshal, 1997). analyze two propositions about the effects of organization-level factors and personnel management practices on innovation capability drawn from in-depth comparative case studies of 24 cross-fiinctional innovation teams of three companies, which is not presented in this paper. These propositions are tested using surveys of 182 cross-functional innovation teams of 38 large companies in the computer, photo imaging, and automobile industries whose task was to use market knowledge about products and services response to customer to generate innovation in demands. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses the theory and hypotheses. Section 3 presents the research design. Section 4 provides the results, and section 5 presents the discussion and conclusions. THEORY AND HYPOTHESES This paper draws on and integrates two streams of literature that discuss organizational innovation capability: the resource-based theory of the firm and innovation literature that focuses on the organization level differentiation framework. level processes of analysis which is strongly The two propositions analyzed -cross-functional communication by the integration- influenced in this paper are: (1) The organization- frequency, shared mental model of cooperation, and overlapping knowledge- support the innovation capability. (2) Organization- level persoimel management practices -selection, reward and control on reward, orientation, and development, and team-based work patterns- not only support the innovation training capability directly but also indirectly by supporting the organization-level processes that facilitate this capability. Organizational innovation capability Organizational innovation capability concerns an organization's ability to combine different types creating new of resources, especially firm-specific knowledge embodied in their employees, for resources that enable firms to achieve and sustain their competitive advantage. Organizational capabilities are viewed as a type of strategic resource, because it is rare, valuable. non-tradable, inimitable, organizational and non-substitutable (Barney, capabilities knowledge embedded study, this I focus on These knowledge, and combine and convert in different disciplines for creation results in innovation in products and/or processes. that In of mobilizing and creating knowledge for innovation. capabilities are specified as a firm's ability to mobilize individual 1991). of new knowledge that Moreover, these capabilities are dynamic in they involve the interaction and changes between firm's internal knowledge and the demands of the external market (Helfat and Raubitschek, 2000). In other words, it involves the continuous integration and combination of knowledge from the external market with the internal knowledge and capabilities of the firm such that the constantly met. Some demands of the external market are concepts of organizational capabilities are: "core capability" related (Leonard-Barton, 1995), "organizational routines" (Nelson and Winter. 1982; Winter, 2000), "core competence" (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990), "combinative capability" (Kogut and Zander, 1992), and "dynamic capability" (Teece, Pisano and Shuen, 1997). I argue that the literature on organizational capabilities tends to either emphasize knowledge mobilization Zander. 1992; Teece Barton (1995) who (e.g.. et al., tries to Nelson and Winter. 1982; Prahalad and Hamel, 1990; Kogut and 1997) or creation argue for both. (e.g.. Nonaka and Takeuchi. 1995) with Leonard- Researchers that emphasize knowledge mobilization tend to assume creation occurs and that the critical facilitating factors deal with individuals' motivation to share or mobilize their individual knowledge. For researchers who emphasize the creation process, individuals are boundedly rational, and therefore, even if the motivation problem for knowledge sharing lead to new is solved, knowledge that is being mobilized or shared does not resources creation. Since individuals are boundedly rational, they face the problems of absorbing and converting knowledge that is being shared and convert it into organizational knowledge because of knowledge specialization in organization. I propose that this limitation is solved by having individuals with the absorptive capacity for different types of knowledge that Therefore, in developing the capability to mobilize and create knowledge for being shared. irmovation, mobilization, for (e.g., management organization design or personnel motivate knowledge sharing are knowledge is practices that and the conversion process requires overlapping critical, Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Leonard-Barton, 1995). Organization-level processes and innovation capability In this facilitators paper 1 analyze three organization-level factors that are often discussed as of innovation capability: organization members (1) in the daily context Cross-functional communication organization shared vision (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990), 1990), and the understanding by organization knowledge members of how the is individuals inside the organization (Leonard-Barton, innovation capability. the different thought worlds fit overlapping together as a system; (3) knowledge of disciplinary 1995). These three factors support the Cross-functional communication frequency and the shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation facilitates the individuals that embodies the commitment (Lincoln and Kalleberg, (Dougherty, 1992) or organization subcultures (Schein, 1996) overlapping among of the organization (Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967); (2) The organization-level shared mental model of cooperation of Organization-level frequency facilitate knowledge mobilization, and overlapping knowledge process of new knowledge creation. Organization-level communication frequency influences the cross-functional communication in organizations has a positive effect frequency. Cross-functional on the innovation capability, as amount of knowledge mobilized or exchanged between and among it different functions (Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967). Cross-functional communication frequency supports innovation, since innovation requires the sharing and integration of different types of ftinctional knowledge (Dougherty, 1992). Innovation is most effective when individuals in sales/marketing provide knowledge and information about customer preferences, and design and manufacturing engineers provide their knowledge and expertise on how to design and manufacture the products. Organizations have different communication channels or routines (Nelson and Winter, 1982), and communication is viewed as knowledge and information exchange knowledge mobilization for innovation. Inside the organization, the that facilitates or hinders communication routines may be mainly internal within the same function or external across different functions, depending on the design of the organization or on In organizations, frequent how employees are managed (Lawrence and Lorsch, communication between and across different 1967). functions enhances innovation (Nohria and Ghoshal, 1997). Other studies have documented the importance of inter- unit communication for the creation organizations (e.g. Ghoshal et al., the better the innovation, as there and diffusion of innovations within complex multiunit 1994). is The more frequent the cross-functional communication, more knowledge being mobilized. These ideas lead to the hypothesis that: Hla. Organization-level cross-functional communication frequency innovation, as an outcome of the innovation Organization-level shared is positively related to capability. mental model of cross-functional cooperation. organization-level shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation deals with the which individuals in different functions view the organization. The way in Depending on the organization, individuals view different functions as coalitions of interests (Cyert and March, 1963) or as a cooperative system (Barnard, 1938). Organization-shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation embodies the organization-shared vision (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990), commitment (Lincoln and Kalleberg, 1990), and the understanding of organization subcultures (Schein, 1996) fit how the different thought worlds or together as a system. Therefore, an organization- shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation not only embodies the collective goals and aspirations of organization members how knowledge embedded new resources. (Tsai and Ghoshal, 1998), but also their understanding of in different disciplines links together The common vision and knowledge in different functions is linked together facilitates the knowledge to mobilize, organization-shared how and mental best to model mechanism that helps different parts Hence, hypothesized it is for creating commitment help organization members knowledge and information mobilization. potential value of their when necessary exchange and integrate of cross-functional of the organization to it to see the The understanding of how process of identifying which for innovation. Therefore, the cooperation serves combine knowledge as bonding a for inno\'ation. that: Hlb. The organization-level shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation is positively related to innovation, as an outcome of the innovation capability. Organization-level cross-functional overlapping knowledge. 0\'erlapping knowledge supports individual knowledge conversion into organizational resources. Overlapping knowledge deals with the overlapping disciplinary knowledge in the organization. Organization that possess overlapping knowledge in disciplines they overlap. in its two ways. own First, as in other disciplines This absorptive capacity members have absorptive capacity for knowledge facilitates the knowledge creation processes each function or a community of practice (Brown and Duguid, 1991) has thought world where knowledge is embedded, the overlapping knowledge in other functions enables individuals to take the perspective of other functions during the process of knowledge exchange with members from those functions in the process of innovation (Boland and Tenkasi, 1996). Second, individuals with the overlapping knowledge of other functions possess absorptive capacity for receiving knowledge from other ftinctions. as their overlapping knowledge enables them with their logic is own to take the perspective of those functions when combining knowledge function in the process of innovation (Boland and Tenkasi. 1996). that overlapping knowledge sets The underlying provide individuals with the cognitive capability and absorptive capacity to combine insights synergistically, effectively, and efficiently from multiple knowledge Hlc. sets for innovation. This leads to the hypothesis that: Organization-level innovation, as cross-functional an outcome of the innovation overlapping knowledge is related positively to capability. Personnel management practices and innovation capability Since organizational innovation capability knowledge embodied or processes, in employees how employees are for is about the ability of the firm to mobilize combination and creation of new resources, managed influence i.e. products some the innovation capability. While researchers suggest that the reward systems motivate knowledge mobilization for innovation (e.g. Manners employees that et al., 1983), others suggest the initial socialization or orientation of encourage the building of social ties new (Nohria and Ghoshal, 1997), training and development of certain groups of employees, particularly the engineers (Basadur, 1992), or the combination of these practices (e.g. Shapero, 1985). support the innovation capability. Organization-level selection. High-performing organizations carefully screen employees for personality traits that are conducive critical for innovation, in addition to Applying create this idea to new knowledge to team work environment for knowledge sharing using other irmovative practices (Ichniowski et an organization that organizes into project resulting in innovation, selecting teams to share al., that is 1997). knowledge to employees based on behavioral factors conducive to knowledge mobilization enhances new resources creation, i.e., innovation. These discussions lead to the hypothesis that: H2a. Organization-level selection based, sharing is in part, positively related to innovation, as Organization-level reward on behavioral factors conducive an outcome of the innovation systems. Organizations with knowledge to capability. extensive mobilization, reward employees based partly on these behaviors (Aoki, 1988). knowledge The author suggests that the willingness to exchange knowledge and information in Japanese firms is not determined by their cultural value systems but by the reward system that encourages these behaviors. Robinson (1996) also shows that in Japanese companies the reward system for non- management employees not is only based on individual-based performance but also on behavioral factors, particularly attitudes related to cooperation, and knowledge and information sharing. Moreover, the survey conducted by the Japanese Ministry of companies use factors that related to promotion. in rewarding employees, also shows that morale building, which cooperation and knowledge sharing, I hypothesize Labor (1987) analyzing the is a critical factor in is bonus payment and that: H2b. Organization-level reward system based, in part, on cooperative behaviors is positively (e.g.. Katz and related to innovation, as an outcome of the innovation capability. Organization-level control over individuals' rewards. Previous studies Allen, 1985) suggest that organizations with the innovation capability also grant the project managers some control over individuals' rewards. Japanese firms superior innovation capability (Nonaka and Takeuchi, individuals' that are considered to have 1995) also divide the control over rewards between functional and non-functional managers (Robinson, 1996). In Japanese firms, both the functional and personnel managers have influence on the individual 10 reward system. While functional managers have influence on individual performance evaluation, personnel managers have the final say in the overall performance evaluation and reward of employees. Personnel managers decide on individual job assignment, bonus payment, and promotion. On the other hand, in capability (Clark and American Wheelwright, firms, which are considered to have lower innovation 1992), functional managers exercise sole control individuals' rewards (Aoki, 1988; Robinson, 1996). Based on these analyses, I hypothesize H2c. The organization-level reward system that divides the control over individuals between functional and non-functional managers outcome of the innovation is over that: rewards ' positively related to innovation, as an capability. Organization-level work patterns. The use of team-based work teamwork performance (Basadur, 1992; Ichniowski patterns enhances Since innovation requires the et al., 1997). use of project teams (Clark and Wheelwright. 1992), this study applies this concept to project team performance and argues that organizations that team-based work patterns performing daily first in tasks. In Japanese firms, when new employees arrive in a given department, they are not assigned a task to perform alone, but with others in carrying out tasks (Robinson, 1996; Aoki, 1988). Moreover, participation on cross-functional problem solving teams, such as quality in have superior innovation capability also use Japanese firms than in their US circles in the daily context of organization facilitate when organized into project how to work on teams. teams for innovation, they bring knowledge and knowledge mobilizafion and creation analyses lead to the hypothesis also higher counterparts (Aoki, 1988). Since daily tasks are organized based, in part, on teams, employees acquire knowledge and skills on Therefore, is that: 11 for innovation (Staw et al., 1981). skills to These H2d. Organization-level cross-functional work pattern outcome of the innovation is positively related to innovation, as capability. Organization-level cross-functional socialization. Cross-functional orientation functional socialization of to new employees have an new employees. Companies is cross- that provide cross-functional orientation higher innovation capability than companies that do not use this practice (Nohria and Ghoshal. 1997). These authors suggest that Japanese firms have superior innovation capability, compared socialization of to their European and American competitors, new employees, which exposes them exposure enables employees to build social ties hired R&D scientists capability of North and engineers in to different parts Other studies in different parts (e.g.. American and Japanese firms Japanese firms are because of the initial of the organization. This with other employees organization that encourage knowledge exchange. compare the innovation in part, initially of the Basadur, 1992) that also show exposed to that the newly sales organization, then to manufacturing and other engineering organizations. These discussions lead to the hypothesis that: H2e. Organization-level cross-functional orientation outcome of the innovation is positively related to innovation, as an capability. Organization-level cross-functional development. Previous research also argues that cross-functional development of employees enhances the innovation capability (e.g., Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Leonard-Barton, 1995), especially the creation process. This practice differs from cross-functional orientation in that these organizations, but also to help its purpose is not only to give employees exposure to them acquire knowledge and that usually takes a longer period of time to accomplish. compare the development of engineers in US skills in these organizations Westney and Sakakibara (1986), who and Japanese computer companies, show that the 12 career paths of engineers in Japanese companies include spending an extended period of time in R&D manufacturing and organizations. US companies, however, do not use (Leonard-Barton, 1995). Based on these analyses, 1 hypothesize H2f. Organization-level cross-functional development outcome of the innovation An Human indirectly by communication that: positively related to innovation, as resource frequency, the management model mental Organization-level orientation, affect processes, organization-level shared also practices overlapping knowledge, that are proposed to support of cross-functional social it On cross-functional particularly cross-functional cooperation, and and shared mental communication, orientation, or the initital socialization of employees, serves two purposes that enhance the organization's for innovation. innovation capability the this capability. model of cross-functional cooperation. Cross-functional functions, ability to the one hand, by exposing mobilize knowledge employees to different encourages cross-functional communication frequency through the building of networks in these functions (Galbraith, knowledge and information with those with and Ghoshal. 1998). individuals will On 1 977), so that individuals are whom willing to share they have had prior social interaction (Tsai the other hand, the initial orientation view the organization (Louis, 1980) more for the rest is critical in shaping how of their careers. Upon entering the organization, individuals are exposed to different organization functions, and cognitive maps of their surroundings (Katz, 1997:26) will include these different "territories" and the way which they an of personnel management practices on organizational innovation affecting and new knowledge practice capability. indirect effect capability. is this all link in together as a cooperative system (Barnard, 1938), replacing individual goals with the goal of the organization (Ouchi, 1979). 13 Therefore, cross-functional orientation builds organization-level shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation that encompasses shared commitment (Lincoln and Kalleberg, how knowledge embedded 1990). shared goal (Ouchi, 1979), and the understanding of in different disciplines may be linked together for innovation. These discussions lead to the hypotheses that: H3a. Organization-level cross-functional orientation is positively related to organization-level is positively related to organization-level cross-functional communication frequency. H3b. Organization-level cross-functional orientation shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation. Organization-level control over individuals' rewards and organization-level cross- functional communication frequency. The nature of managerial control over individuals' rewards affects communication patterns functional managers have vertical, all in organizations (Morrill, 1995). the control In the organization on individuals' rewards, communication tends where to be within the same function, between superior and subordinates, with limited cross- functional communication. In the organizations where the influence is from within and outside the functions, communication tends be both within and across different functions. The rational actor model (Milgrom and Roberts, 1992) individuals have the incentive to communicate influence on their rewards, and reward. Therefore, if this who to divided among managers also suggests that more frequently with managers who have influence decisions of other in performance evaluation and influence is divided among managers from individual functions, employees have the incentive to within and outside communicate across functions to influence decisions on their performance evaluation and reward. Over time, these communication patterns become routinized in the organization (Morrill, 1995). These discussions lead to the hypothesis that: 14 HSc. Control over individuals managers is ' rewards that divided between functional and non-functional is positively related to organization-level cross-functional communication frequency. work Organization-level communication frequency. The use of facilitates cross-functional on cross-functional task and patterns organization-level cross-functional work patterns such as task communication frequency (Galbraith. 1977). forces, their exposure to individuals cross-functional from When individuals exposure tended to communicate more frequently cross-functionally knowledge and information as needed for their daily tasks than did those (Newport, 1969). Moreover, individuals more frequently outside who had their functions, but also this work different functions facilitates network formation, which encourages cross-functional communication. Individuals this forces who gained in order to acquire who lack the exposure exposure not only tended to communicate tended to use richer means of communication, such as using face-to-face meetings and phone conversations, rather than the written forms of communication used by individuals who lacked the exposure (Newport. 1969). These analyses lead to the hypothesis that: H3d. Work patterns that include the use of cross-functional teams are positively related to organization-level cross-functional communication frequency. Organization-level cross-functional development, communication frequency, shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation, and overlapping knowledge. Cross-functional development is a process training and/or career and skills whereby employees development for are sent to different functions through on-the-job an extended period of time, in order to acquire of those functions. Cross-functional development serves three purposes the innovation capability: (1) The benefit that is most frequently discussed knowledge in facilitating in the literature is that cross-functional development enables the acquisition of redundant knowledge (Leonard-Barton, 15 1995; Nonaka and Takeuchi, knowledge and that facilitate facilitates the skills 1995); (2) Through cross-ftinctional development, while acquiring from different functions, employees also form networks cross-functional communication; and Cross-functional (3) development also formation of organization-shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation. While acquiring redundant knowledge and forming networks communication, individuals also gain a these functions and the integrated in these functions way when necessary in better understanding which knowledge embedded for innovation. is facilitate cross-functional of the different thought worlds of in these functions These analyes lead H2e. Organization-level cross-functional development that may be shared and to the following hypotheses: positively related to the organization- level overlapping knowledge. H3f. Organization-level cross-functional development is positively related to organization-level is positively related to organization-level cross-functional communication frequency. H3g. Organization-level cross-functional development shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation. RESEARCH DESIGN Data were gathered through surveys of 182 cross-fiinctional innovation teams of 38 large US that and Japanese multinational firms have operations in in the computer, photo imaging, and automobile industries the United States. The analysis of companies present in different industries facilitates the generalization of results across industries. Selection Criteria The industries were selected because they face computer industry, medium-sized in the different innovation cycles -short in the photo imaging industry, and long 16 in the automobile industry- that affect the time pressure on gathering and processing different types of knowledge for innovation (Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967). The companies were selected based on two factors. First, they respective industries based on revenue as reported in the Hoover's were the largest in their HandBook of World Business (1999). Second, they had customer service centers in the United States and Japan dealing with similar products. This requirement compares sources of was necessary because this capability of US this study is part of a larger study and Japanese multinational enterprises in that both the United States and Japan. For each company, the largest customer service center the United States was Affiliations (1998). selected. 1992). The customer was service organization demands and service terms of employees located in These centers were identified using the Directory of Corporate The customer linking tlrm's external in selected it is the gatekeeper and manufacturing capabilities (Quinn, internal design centers selected because had at least three sales/marketing, customer service, and engineering linking to the functions R&D represented: and manufacturing organizations. In each customer service center, a selected. Project set of cross-functional project teams was randomly teams were selected based on three represented: customer service, engineering (i.e. criteria. First, at least three R&D functions were or manufacturing) and sales/marketing or manufacturing. Second, the main objective of the team was to transform specific external customer feedback obtained from the firm's worldwide operations about innovation. Data Collection 17 their products into an There were three steps to the data collection process. First, in depth field interviews, observations and phone interviews were conducted to ensure a deep understanding of the phenomenon. Second, a pilot study was conducted to test the variables and measures and survey instruments. Finally, the surveys were conducted. In order to avoid single respondent bias and separate out levels of analysis, 1 collected data from three different sources using three separate surveys (Rousseau. 1985). Data on the organization-level processes and practices were collected from a personnel firm, because a personnel function knowledge about the more interaction is a boundary function and therefore this manager of each manager has the best between and among different functions and can speak about it objectively. The data for the project team-level outcomes of innovation capability were collected from both the project team leaders and the project managers. For each compan>- the project manager was asked list, to provide a list of projects and the team leaders randomly selected team leaders were asked conducted on three companies and their teams some consistency (r > 0.40, p > .05). Based on to take a survey. Prior to this, surveys to this were examine the consistency between answers provided by the team leaders and core team members. suggest that supervised them. Results from the correlation analysis However, in order to minimize bias on team performance, instead of using team leaders' answers, project managers" evaluations of these projects are used (Ancona and Caldwell, 1992). The response rate was 88.4%. Variables and measures The management at variables and measures are based practices, organization-level processes, on the following constructs: Personnel and outcomes of the innovation capability both the organization and project levels. Variables preceded by O- refer to organization-level 18 variables, variables with the prefix P- indicate project team-level variables, start and variables that with C- are controls. The innovation The capability. innovation capability is measured organization and at the project levels. At the organization level, innovation is organization's level of success in incorporating external customer feedback from new operations in at the measured by its worldwide product development, product modification, and the number of products developed within the measures for both last five years (a = 0.84). Effectiveness and efficiency are also used as For effectiveness, customer satisfaction with the irmovation this capability. measured by ratings given by JD Power & is Associates for the automobile companies in terms of "dependability", "appearance", and "overall quality", and an external marketing research company for PC World companies in the computer companies, for the photo imaging industry (a = 0.87). At the project level, measured by the extent to all the measures are averaged by the organization. which projects using customer feedback development and/or modification (0.87). Efficiency is measured by resources used in completing the project measure efficiency (a measured by the extent to = led Innovation to staff hours 0.70). new product and financial Speed-to-market which the innovation was delivered quickly enough to is is customers to satisfy them. Personnel management practices. more realistically, and one capability. in In order to capture personnel management an in-depth comparative analysis of three companies, two located Japan, was conducted to The personnel management understand how companies develop the practices in the USA innovation practices analyzed in this study are, therefore, based not only on previous research, but also on personal interviews and on first-hand observations of 19 these companies. The company knowledge mobilization and the Facilitators practices are divided into practice that facilitates of knowledge mobilization two groups, those knowledge are: (1) Selection based on "ability to work on team" and "the willingness to creation. (0-SELECT), which salary increase, job to (0-RWRD) assignment, bonus payment, and promotion coded = 0.79). (3) from performance (0-XCNTRL) have on how much individual promotion and job assignment (a = 0.91). influence the project managers managers" control, since in the American context, personnel managers have on the individual reward system. I analyzed project little or no influence (0-ORlEN) was measured by (4) Cross-functional orientation whether companies put new professional employees through cross-functional orientation the operational and corporate levels (a = 0.81). (5) whether daily task requires the use of team, and cross-functional teams on quality circles (a The which is facilitator in this Nature of managerial control on individuals" rewards was determined by increase, selection which "cooperative behaviors" have any impact on individual evaluation forms used by companies (a salary is cooperate" coded from the evaluation forms used for recruiting by companies (a = 0.73). (2) The reward structure system consists of the extent that faciHtate = Work pattern (0-WKPTRN) if so, the level is at both measured by of employee participation on 0.73). of knowledge creation is cross-ftmctional development measured by whether companies put their professional (0-DEVLOP), workforce, particularly engineers, sales/marketing, and customer service personnel, through on-the-job training, off-the- job training, and job rotation in other functions, particularly R&D, sales/marketing, and manufacturing (a = 0.76). Organization-level processes. into those practices that facilitate The organization-level process variables are also divided knowledge mobilization and the practice 20 that facilitates knowledge Facilitators creation. communication knowledge of (0-XCOM), frequency which communication frequency (dealing with work •on personal time, employees (a = (0-MODEL), i.e., measured is related issues) coffee breaks, after work) the measures are the extent to individual functional goal (a overlapping knowledge = R&D, by The facilitator (0-OVERLAP). which and manufacturing. I cross-functional cross-functional formal model of cross-functional cooperation in different functions share the commitment toward achieving 0.78). (1) and informal (not work-related and which employees is domains through on-the-job, off-the-job sales/marketing, are: among management and non-management rank 0.73). (2) For organization-shared mental vision of the organization and their training mobilization it as opposed of knowledge creation is to focus on cross-functional measured by the summation of overlapping training, and job rotation of engineers select these training practices in because they factor together (0.77). The They are control variables are industry dummy (C-INDUSl, C-INDUS2) and country (C-JAPAN). variables. Methods of analysis The Tobit method is used to analyze the data since the dependent variables were constrained to an interval. The models use alternative measures of the outcomes of the innovation capability both project team at the organization level (innovation and customer satisfaction) and level (innovation, efficiency, and speed-to-market). Hypotheses (HI a, Hlb, Hlc), which analyze the relationships between the organization-level processes and the innovation capability, are tested using the following model: Outcomes of the innovation capability = a + + p4 . C-INDUSl + Ps • C-INDUS2 + p(, • Pf 0-XCOM + /?. O-MODEL • C-JAPAN +e 21 + p} ^O-OVERLAP For testing the direct effect of personnel management practices on the innovation capability (H2a-H2f), the following specifications are used: Outcomes of the innovation capability = « + + p4 * O-ORIEN + C-JAPAN + /?5 . 0-WKPTRN + fie • /?/. O-SELECT + fi: • O-RWRD O-DEVLOP + p- C-INDUSl + . Ps + Pi - * O-XCNTRL C-INDUS2 + Pg . E For testing the indirect effect of personnel management practices on the organizationlevel processes that support the innovation capability 0-XCOM =a + Pi' O-XCNTRL INDUSl + P6 C-INDUS2 + » O-MODEL JAPAN + p- . (H3a-H3g), the following models are used: + p2 • O-ORIEN + Pj C-JAPAN + . 0-WKPTRN + p^ • O-DEVLOP + p5 . C- s = a + Pi* O-ORIEN + p: • O-DEVLOP + p} - C-INDUS1+ p^ * C-INDUS2 + p, • C- s 0-OVERLAP = a + pi' O-DEVLOP + p: * C-INDUSl + ps . C-INDUS2 + p4 C-JAPAN + e • ANALYSIS AND RESULTS Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. relatively high correlation The between the dependent and independent measures. results The show relatively small correlation coefficients between the independent variables suggest they are distinct from each other, and they thus demand independently treatment Insert Table 1 in this analysis. about here Table 2 presents the results from testing hypotheses (Hla-Hlc). The results support hypotheses HI a, Hlb, and Hlc, and the proposition that the organization-level processes, particularly cross-functional communication frequency, organization-shared mental model of 22 cross-functional cooperation, and cross-functional knowledge, overlapping support the Cross-functional communication frequency and overlapping knowledge innovation capability. support innovation and customer satisfaction with the innovation at the organization level. At the project level, both factors support efficiency in the process of creating innovation, speed-to- market, and product innovation. Specifically, Model shows 1 communication frequency and overlapping knowledge have a positive innovation. Model shows 2 also that these two effect factors have a positive effect on product on customer Shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation has a negative effect on satisfaction. customer satisfaction with the innovation. One explanation could be creative abrasion (Leonard-Barton, 1995), and too that cross-functional effect cross-functional that much that innovation also requires cooperation reduces it. Model 3 shows communication frequency and overlapping knowledge have a positive on product innovation. Model 4 shows that cross-functional communication frequency and overlapping knowledge support efficiency. Model 5 shows that cross-functional communication frequency and overlapping knowledge have a positive relationship innovation. Among these two factors, to speed-to-market of the however, cross-functional communication seems to have smaller effect on product innovation than overlapping knowledge but greater effect on other outcomes of this capability. *=!< + **** + * + + * + * + + **** Insert Table 2 about here Table 3 presents the results from testing hypotheses (H2a-H2f). The results from these analyses support hypotheses H2a, H2b, H2d, and H2e, and the proposition that personnel management practices have a direct effect on the innovation capability. Model 1 shows that selection, reward, cross-functional orientation, development have a positive effect on product innovation. 23 and cross-functional Influence of project manager on individual reward system and team-based innovation, which is contrar>' to the work hypotheses pattern do not have any H2c and H2f. Model 2 effect on product shows that cross- functional orientation and cross-functional development have a positive effect Model satisfaction with the innovation. 3 shows that selection, control on customer over individuals' rewards, and cross-functional development have a positive relationship with product innovation at the project level, while reward and cross-functional orientation have a negative effect on product innovation at the project level. At the project level. Model 4 shows over that reward, control individuals' rewards, and cross-functional orientation, cross-functional development, and team- based work patterns have a positive effect on efficiency at the project level. Model shows 5 that the control over individuals' rewards and cross-functional development have a positive effect on Overall, cross-functional development speed-to-market of the innovation. seems to support a wider range of outcomes of capability, followed by control over individual's rewards, crossfunctional orientation, reward behaviors, and select behaviors. Insert Table 3 about here Table 4 presents the results from testing the indirect effect of personnel management practices on the innovation the process of capability by affecting the organization-level processes knowledge mobilization and creation (H3a-H3g), and the results demonstrate Model functional 1 indicates communication that not for innovation. The hypotheses tested are that all hypotheses are supported. only does cross-functional orientation frequency, that support control over individuals' rewards, facilitate cross- cross-functional development, and the use of cross-functional work patterns also have a positive effect on crossfunctional communication frequency. strongest effect, as indicated by its Cross-functional coefficient. Model 24 2 work shows patterns, however, has the that cross-functional orientation and cross-functional development Model The 3 shows facilitate that cross-functional show overall results shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation development that personnel is positively related to overlapping knowledge. management practices also support the innovation capability indirectly by supporting the organization level processes that support this capability. Of all the practices, however, cross-fianctional development supports processes analyzed in this study. Cross-functional all three organization-level development supports cross-functional communication frequency and overlapping knowledge, which support the organizational innovation capability, and shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation, which supports it at the project level. ********* + + Insert Table The results management show that for :(; Ht ******* * 4 about here innovation as an outcome of the personnel practices and processes support this capability. Specifically, for innovation, cross- functional communication frequency and overlapping knowledge support communication frequency also supports other outcomes of this speed-to-market. innovation innovation, at the For overlapping knowledge, it also it. Cross-functional capability such as efficiency, and supports customer satisfaction with organization level, and efficiency, speed-to-market, and product innovation at the project level. Among personnel management practices, selection of employees based on behavioral factors such as their ability to work on team and the willingness to cooperate, reward based on cooperative behaviors, cross-flinctional orientation, and development directly support innovation as an outcome of this capability. Surprisingly, the control of project rewards and cross-functional work pattern do not support project manager over individuals' rewards supports other 25 this. manager over individuals' However, the control of the outcomes of this capability at the project level, efficiency, speed-to-market, and product innovation. work pattern also enhances efficiency in the process of The use of cross-functional knowledge mobilization and creation for innovation. Moreover, these management practices also support this capability indirectly the organization-level processes that also support the capability. The by supporting control of project manager over individuals' rewards, and cross-functional orientation, cross-functional development, and work the use of cross-functional Among communication. patterns, facilitate cross-functional these practices, cross-functional orientation and development facilitate the building of shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation. And, cross-functional development also enables companies to accumulate overlapping knowledge that enhances a wide range of outcomes of this The downside of these capability. practices seem to model of cross-functional cooperation has a negative with innovation of the company (see Table be that the organization shared mental effect on the overall customer satisfaction 2). DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS This paper shows the specific organization-level factors and management practices that facilitate knowledge mobilization and However, the story of how measure capability different factors firms that this capability is directly but its creation is developed to support different compete on product innovation, is and therefore is the innovation not so simple. Since capability. we cannot outcomes, depending on the outcomes desired by the firms, and practices seem knowledge mobilization facilitates creation, cross-functional the outcomes of organization-level this capability. process that First, for facilitates communication frequency and the factor overlapping knowledge, 26 in particular, the redundancy among that R&D, manufacturing, and sales/marketing. The management practices that seem to support knowledge mobilization are: selection of employees performance, but also their character cooperation in organization. based, traits that Moreover, reward is not to on their are conducive to individual potential knowledge sharing and based, not only on their individual explicit output, but also behavioral factors such as cooperation. and development seem only In addition, cross-functional orientation be also important. Second, for companies that consider customer satisfaction with their innovation to be important, cross-functional communication and overlapping knowledge At the same time, such firms may need seem to be important. to be cautious with the organization shared mental model of cross-functional cooperation, since too much cooperation may reduce the creative abrasion that is also necessary for irmovation. Cross-functional orientation to be important for this and development also appear outcome of capability. Third, for companies that place high value on efficiency, cross-functional communication On frequency and overlapping knowledge are important. communication frequency supports the facilitate facilitates new knowledge creation process. also Fourth, if speed-to-market considered. Among the management are reward based, in part, practices that on behavioral seem to factors, on individuals' rewards between functional and project managers, cross- functional orientation, the use of team-based . one hand, cross-functional knowledge mobilization while overlapping knowledge knowledge mobilization and creation the division of control the Specifically, is work and cross-functional development. considered important, then similar factors and practices are cross-functional knowledge may be important. The patterns, communication frequency and overlapping specific practices that are critical include division of control 27 over individuals' rewards between functional and project managers, and development of professional employees cross ftinctionally. summary, In it seems that organization-level cross-functional communication frequency and overlapping knowledge are the most important organization-level factors knowledge mobilization and capability. As found creation, as they facilitate creation process. functional in the case analysis, organization-level cross-functional facilitates Moreover, although various personnel management practices communication frequency, only cross-functional development seems communication the most critical to facilitate both R&D it seems organization-level factor in developing the innovation capability functional development of professional employees. between knowledge facilitate cross- cross-functional communication frequency and overlapping knowledge. Therefore, the supporting a wide range of outcomes of this knowledge mobilization, while overlapping knowledge facilitates in is that cross- This practice entails rotating engineers and manufacturing, and providing them with some off-the-job training sales/marketing. 28 in REFERENCES Aoki, M. 1988. Information, incentives, and bargaining Cambridge University 1991. B. J. Management . Firm Cambridge, . and resources . sustained MA: Harvard University Press. competitive advantage. Journal of 17: 99-120. Basadur, M. 1992. Managing creativity: 6: Japanese economy Cambridge: Press. Barnard, C. 1938. The Functions of executive Barney, in the A Japanese model. Academy of Management Executive . 29-40. Boland, R., and Tenkasi, R. 1995. Perspective making and perspective taking knowing. Organization Science 6: 350-373. in communities of . Brown. J. S.. and Duguid. Organization Science 1: Organizational 1991. P. , learning and communities-of-practice. 40-57. Clark, K., and Wheelwright, S. 1992. Organizing and leading "heavyweighf development teams. California Management Review 34:9-28. , Cyert, R. M. and March, J. G. 1963. A behavioral theory of the firm . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Directory of corporate affiliations. 1998. Directory of corporate affiliations Vol. I-IV . New Providence, NJ: National Register Publishing. Dougherty, D. 1992. Interpretative barriers to successful product innovation Organization Science, 3 : in established firms. 179-202. Knudsen, C. and Montgomery, C. A. 1995. An Exploration of common ground: integrating evolutionary and strategic theories of the firm. In C. A. Montgomery (Ed.), Resource-based and evoludonary theories of the firm: towards a synthesis Boston, MA: Foss, N. J., . Kluwer Academic Publishers. Galbraith, K. 1977. Organization design Reading, . Ghoshal, S., Korine, H., and Zsulanski, G. corporations. Management MA, Addison- Wesley Publishing Company. 1994. Interunit communication in multinational Science, 40: 96-1 10. 29 Godfrey, P. C, and W. L. 1995. The problem of unobservables Management Journal 16: 519-533. Hill, C. research. Strategic in strategic management , and Raubitschek, R. S. 2000. Product sequencing: Co-evolution of knowledge, capabilities and products. Strategic Management Journal 21(10-11): 961-980. Helfat. C. E., . Ichniowski, C, Shaw, K., and Prennushi, G. 1997. The effects of human resource management on productivity: 87:291-313. practices A study of steel finishing lines. American Economic Review , Japanese Ministry of Labor 1987. Rosei Jiho No. 2973 and No. 2853. Katz, R. 1997. Organizational socialization. In R. Katz (ed.). technological innovation: A collection of readings . The human side of managing Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Katz, R., and Allen, T. 1985. Project performance and the locus of influence in the Academy of Management Journal 28: 67-87. R&D matrix. , Kogut, B., and Zander, U. 1992. Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities and the replication of technology. Organization Science 3: 383-97. . and Lorsch, J. W. 1967. Organization and environment: Managing and integration Boston, MA: Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University. Lawrence. P. R.. differentiation . Leonard-Barton, D. 1995. Wellsprings of knowledge . Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Lincoln, J. R., and Kalleberg, A. L. 1990. Culture, control, and commitment: a study of work work attitudes in the United States and Japan Cambridge, UK: organization and Cambridge University Louis. M. R. . Press. 1980. Surprise and Sense Making: What newcomers experience in unfamiliar organizational settings. Administrative Science Quarterly 25:226-251. , 30 entering Manners, G., Steger. The human UK: Oxford Milgrom, P., J., R&D staff. In R. Katz (Ed.), A collection of readings Oxford, and Zimmerer, T. 1997. Motivating your side of managing technological innovation: . University Press. and Roberts, J. 1992. Economics, organization and managemen t. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Morrill, C. 1995. The executive way Chicago, . IL: University of Chicago Press. Nonaka, I., and Takeuchi. H. 1995. The knowledge-creating companv: dynamics of innovation Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. How Japanese create the . Nelson, R. R., and Winter, MA: S. G. 1982. An evolutionary theory of economic change Cambridge, . Harvard University Press. Nohria, N., and Ghoshal, S. 1997. The network San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass differentiated . Publishers. Ouchi, W. 1979. Markets, bureaucracy and clans University of California at . Mimeo. Graduate School of Management, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA. Penrose. E. 1959. The theory of the growth of the Firm Prahalad, C. K., and Hamel, G. 1990. . New York, The core competence of the NY: John Wiley. corporation. Harvard Business Review (May-June): 79-91. Quinn, J. 1992. Intelligent enterprise: a knowledge and service based paradigm for industry New Robinson, P. A. 1996. Applying institutional theory Parental control and isomorphism in . York: Free Press. among to the study of the multinational enterprise: personnel practices in American manufacturers Japan Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Sloan School of Management. Massachusetts . Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA. Schein, E. 1996. Three cultures of management: The key to organizational learning in the 21st century . Mimeo, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Cambridge, Institute of Technology, MA. Shapero, A. 1985. Managing creative professionals. Research-Technology Management March, April. 31 N Staw, B., Sandelands, A multilevel Teece, D. J., L.. and Dutton, J. 1981. Threat-rigidity effects in organizational behavior: analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly . 26: 501-524. Pisano, G.. and Shuen, A. 1997. Strategic Management Journal . Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. 509-533. 7: and Ghoshal. S. 1998. Social capital and value creation: The role of intrafirm networks. Academy of Management Journal 4 464-476. Tsai. W., . Westney. D. E., 1 : and Sakakibara. K. 1986. Designing the designers: Computer Technology Review 89(3): 24-3 1 States and Japan. . . 32 . R&D in the United TABLE 1 Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix TABLE 2 The direct effect of management practices on organizational innovation capability TABLE 3 The direct effect of management practices on organizational innovation capability TABLE The indirect effect of organizational 4 management capability practices on organizational innovation 232 7 MOV -^(10/ Date Due MIT LIBRARIES 3 9080 02246 1542 .iJllMlMIillliit . J,,.; IkiMMMliliieiiHa^vaiMMiMteiMri

![Job Evaluation [Opens in New Window]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/009982944_1-4058a11a055fef377b4f45492644a05d-300x300.png)