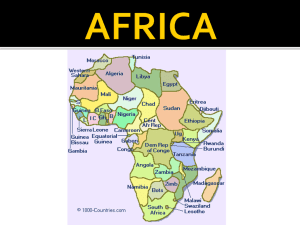

i REFORM, CONFLICT, AND SECURITY IN ZAIRE Steven Metz June 5, 1996

advertisement