Investing in Effective Universal Pre-K: West Virginia’s Path to Success

advertisement

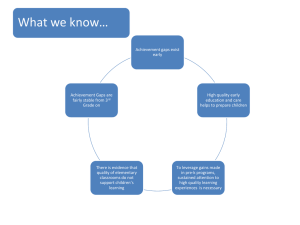

Investing in Effective Universal Pre-K: West Virginia’s Path to Success Steve Barnett, PhD Why invest in Universal Pre-K? First 5 years lay foundations for later success: Language and academic abilities Social development and character The window for change does not close after age 5, but “catch up” is costly Universal Pre-K reaches all children to enhance long-term learning and yield high economic returns Potential Gains from ECE Investments Educational Success and Economic Productivity Achievement test scores Special education and grade repetition High school graduation Behavior problems, delinquency, and crime Employment, earnings, and welfare dependency Smoking, drug use, depression Decreased Costs to Government Schooling costs Social services costs Crime costs Health care costs (teen pregnancy and smoking) Economic Returns to Pre-K for Disadvantaged Children (In 2006 dollars, 3% discount rate) Cost Benefits B/C Perry Pre-K $17,599 $284,086 16 Abecedarian $70,697 $176,284 2.5 Chicago $ 8,224 $ 83,511 10 Barnett, W. S., & Masse, L. N. (2007). Early childhood program design and economic returns: Comparative benefit-cost analysis of the Abecedarian program and policy implications, Economics of Education Review, 26, 113-125; Belfield, C., Nores, M., Barnett, W.S., & Schweinhart, L.J. (2006). The High/Scope Perry Preschool Program. Journal of Human Resources, 41(1), 162-190; Temple, J. A., & Reynolds, A. J. (2007). Benefits and costs of investments in preschool education: Evidence from the Child-Parent Centers and related programs. Economics of Education Review, 26(1), 126-144. Understanding Effect Sizes (ES) •Comparing achievement effects across studies requires conversion to a common effect size •ES of 1.0 roughly equals the achievement gap, so •Effect size of .50 closes ½ the achievement gap •For long-term achievement even effect sizes of .20 yield high economic returns ECE Programs 0-5 in the US: Impacts in 123 studies since 1960 Effects (1sd)= percetn of ach. gap All Designs HQ Designs HQ Programs 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 Treatment End Ages 5-10 Age at Follow-Up Age >10 What determines cognitive gains? Time of Follow-Up Research Design Quality Negative Positive Intentional Teaching Individualization Positive Positive (small groups and 1 on 1) Comprehensive Services n= 123 Studies Negative Effectiveness follows quality: Pre-K achievement gains CPC Language na Tulsa 8 St na .26 Head Start .09 (.13) Math .33 .36 .32 .12 (.18) Literacy na .99 .80 .25 (.34) Effects in standard deviations. Figures in parentheses are adjusted for noncompliance. Results from the Newest Studies • Tennessee: Positive gains in randomized trial as well • Rhode Island: Positive gains for all, larger gains for poor • Boston Pre-K—strong effects on language, literacy, math, and executive function • Arkansas: reading and math grade 2, reading at grade 3 • Oklahoma: Grade 3 gains on attention and math; more former pre-K take tests so underestimate effects on tests. • New Jersey: Grade 5 effects on reading, math, grade ret. • Chicago full-day larger effects on language and math West Virginia Pre-K Enrollment Trends (62% in 2012) West Virginia Pre-K Expenditure Trends How Does West Virginia Compare (2011)? • • • • 5th for enrollment at age 4 3rd for 4s with Head Start (> 80%) 7th for 3s with Head Start (20%) 8th for state funding per child – Considerably above average • 8 of 10 benchmarks for quality standards • 2013 all new teachers required to have BA Keys to Education Quality • • • • • • High standards and sufficient funding Balanced—Cognitive, social, emotional Implemented as designed Well-trained, adequately paid staff Strong supervision and monitoring Use data to inform practice Building Pre-K Quality: NJ’s example • Serves all 3 and 4 yr. olds in 31 high-poverty cities • Certified Teachers paid public school salaries whether public or private • 6 hour educational day plus wrap-around full day/year • Maximum class size of 15 students • State funding per child for a full school day • Evidence-based curricula • Most served by private providers under contract • State Dept. of Ed. continuous improvement system Continuous Improvement Cycle First Develop Standards Measure and Assess Progress Analyze and Plan Implement – Professional Development and Technical Assistance NJ Raised Quality in Public and Private 60 47.4 50 40 34.6 32.2 27.7 30 Percentage of Classrooms 19.9 16.0 20 10 12.1 4.2 3.9 0.0 1.7 0.2 0 1.00-1.99 2.00-2.99 3.00-3.99 00 Total (N = 232) 4.00-4.99 5.00-5.99 6.00-7.00 08 Total (N = 407) ECERS-R Score (1=minimal, 3=poor 5= good 7=excellent) Results of Increased Quality in NJ Pre-K • • • • • Gains in language, literacy, math 2 years have twice the effect of 1 2 years closed 40% of the readiness gap Effects sustained through 2nd grade Grade repetition cut in half at 2nd grade How Should West Virginia Move Forward? Continuously Improve Quality Measure teaching effectiveness and child progress Implement professional development based on results Partner with all Head Starts to raise quality to same standards Increase Intensity and Duration Full-day of engaged time, 2nd half not just lunch & nap Start more children at age 3 Increase Quality K-3 with Continuous Improvement Sys Ensure State and District Capacity for Coaching and TA Conclusions Quality Pre-K can be a good public investment Increased productivity and decreased social problems High-quality state pre-K is producing strong results Quality requires high standards, adequate funding and a relentless focus on continuous improvement Quantity—full-day—matters too Include K-3 in a continuous improvement system West Virginia can expect high economic returns to its continued investment in quality pre-K References 1. Barnett, W. S. (2011). Effectiveness of early educational intervention. Science, 333, 975-978. 2. Camilli, G., Vargas, S., Ryan, S., & Barnett, W.S. (2010). Meta-analysis of the effects of early education interventions on cognitive and social development. Teachers College Record, 112(3), 579-620. 3. Frede, E. C., & Barnett, W. S. (2011). New Jersey’s Abbott pre-k program: A model for the nation. In E. Zigler, W. Gilliam, & W. S. Barnett (Eds.), The pre-k debates: current controversies and issues (pp. 191-196). Baltimore: Brookes Publishing. 4. Gormley, W., Phillips, D., Newmark, K., Welti, K., & Adelstein, S. (2012). Social-emotional effects of early childhood education programs in Tulsa. Child Development, 82, 2095-2109. 5. Hill, C., Gormley, W., & Adelstein, S. (2012). Do the short-term effects of a strong preschool program persist? Working Paper No. 18. Washington, DC: Georgetown Unversity, CROCUS. 6. Lipsey, M., Farran, D., Bilbrey, C., Hofer, K., & Dong, N. (2011). Initial results of the evaluation of the Tennessee Voluntary Pre-K Program. Nashville: Vanderbilt University. 7. Neidell, M., & Waldfogel, J. (2010). Cognitive and noncognitive peer effects in early education. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(3), 562-576. 8. Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., Taggart, B. (2004). The final report: Effective preschool education. Technical paper 12. London: Institute of Education, University of London.