Document 11035884

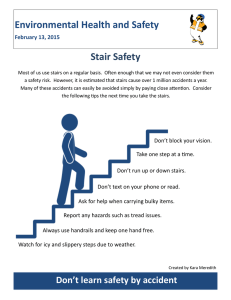

advertisement