Hazard (Edition No. 69) Summer 2009 Victorian Injury Surveillance

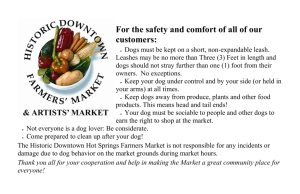

advertisement