Country Studies--Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos Objectives Be aware of the following

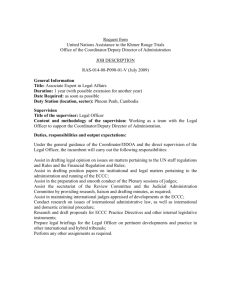

advertisement