by Sabra Elysia Loewus University of Washington

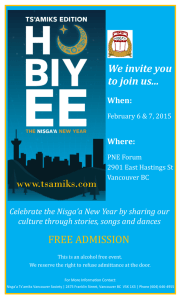

advertisement