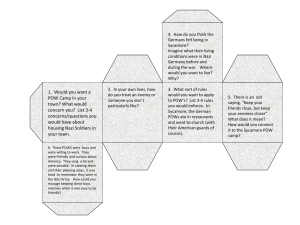

Chapter 17 THE PRISONER OF WAR

advertisement