STRATEGY AND THE REVOLUTION IN MILITARY AFFAIRS: FROM THEORY TO POLICY

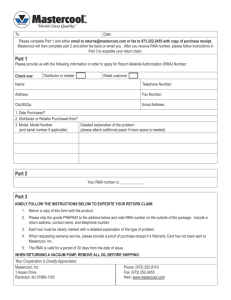

advertisement