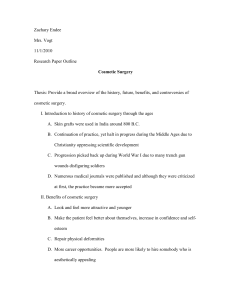

Review of the Regulation of Cosmetic Interventions Final Report

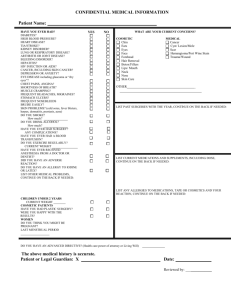

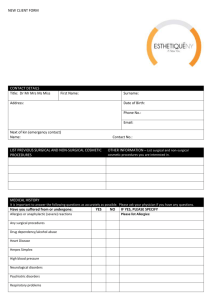

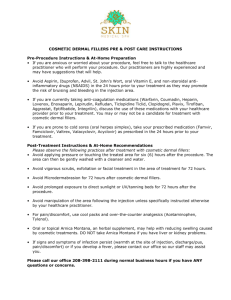

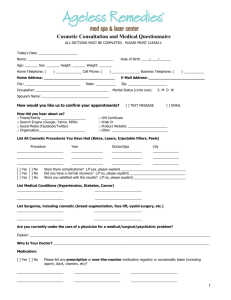

advertisement