Document 11022332

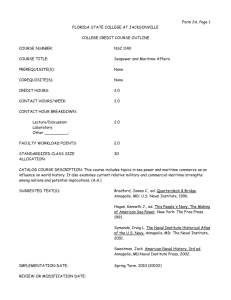

advertisement