Perceptions of the Cognitive Compensation and Interpersonal Enjoyment

advertisement

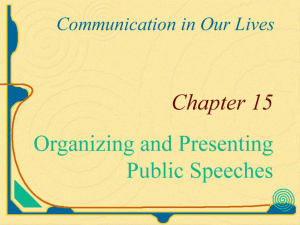

Psychology and Aging 2011, Vol. 26, No. 1, 167–173 © 2010 American Psychological Association 0882-7974/10/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0021124 BRIEF REPORT Perceptions of the Cognitive Compensation and Interpersonal Enjoyment Functions of Collaboration Among Middle-Aged and Older Married Couples Cynthia A. Berg, Ines Schindler, Timothy W. Smith, Michelle Skinner, and Ryan M. Beveridge University of Utah Perceptions of cognitive compensation and interpersonal enjoyment of collaboration were examined in three hundred middle-aged and older couples who completed measures of perceptions of collaboration, cognitive ability, marital satisfaction, an errand task and judged their spouse’s affiliation. Older adults (especially men) endorsed cognitive compensation and interpersonal enjoyment and reported using collaboration more frequently than middle-aged adults. Greater need for cognitive compensation was related to lower cognitive ability only for older wives. Greater marital satisfaction was associated with greater interpersonal enjoyment. These two functions related to reports of more frequent use of collaboration and perceptions of spousal affiliation in a collaborative task. Keywords: collaboration, cognitive compensation, enjoyment of collaboration, married couples, marital quality Supplemental materials: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0021124.supp describe that collaboration is central to the marital relationship in that they work together to make daily decisions (e.g., household purchases) and solve everyday problems (Berg, Johnson, Meegan & Strough, 2003). Such joint problem solving may enhance the support and enjoyment gained from the relationship, especially for older couples as their focus is on the positive emotional regard that can be achieved within relationships (Carstensen & Mikels, 2005; Story et al., 2007). Further, interpersonal enjoyment from collaboration may be enhanced when couples experience greater marital satisfaction (Berg & Upchurch, 2007; Berg, Wiebe, et al., 2008), especially for older couples who describe greater satisfaction in their marriage (Henry, Berg, Smith, & Florsheim, 2007). These two functions, cognitive and interpersonal, may be important in understanding the frequency of collaboration in daily problem solving. Implicit within the aging literature (Dixon & Gould, 1996) is the notion that the frequency of collaboration during late adulthood is greater primarily to the extent that collaboration is needed cognitively. However, given its interpersonal function, the frequency of collaboration may also be greater when it occurs within a satisfied relationship where collaboration is enjoyed (Beveridge & Berg, 2007; Meegan & Berg, 2002). To further examine these two functions we tested how they related to couples’ experience of collaboration as they worked together. The interpersonal enjoyment function of collaboration may relate to couples’ experience of each other as more warm and affiliative. In addition, spouses may see each other as affiliative when they perceive greater need for collaboration (most likely for older adults), interpreting the spouse’s behavior as teaching or tutoring. The primary goal of the present study was to examine whether adults perceived cognitive compensation and interpersonal enjoy- Collaborative problem solving, where two or more individuals work together to perform a task, is thought to compensate for cognitive changes (especially in fluid intelligence) that may occur in late adulthood (Dixon & Gould, 1996; Johansson, Andersoon, & Ronnberg, 2000; Martin & Wight, 2008; Strough & Margrett, 2002). Within a long-term marital relationship, collaboration may also serve an interpersonal function providing support and encouragement as spouses work together. This interpersonal function has not yet been examined within the aging literature. Older couples This article was published Online First October 25, 2010. Cynthia A. Berg, Ines Schindler, Timothy W. Smith, Michelle Skinner, and Ryan M. Beveridge, Department of Psychology, University of Utah. Ines Schindler is now in Cluster Languages of Emotion at the Free University of Berlin. Ryan M. Beveridge is now with the Department of Psychology at the University of Delaware. Portions of these data were presented at the Annual Meeting of the Gerontological Society, November, 2006 in Dallas, Texas. This study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Aging R01 AG 18903 awarded to Timothy W. Smith (PI) and Cynthia A. Berg (co-PI). Ines Schindler was supported by a research fellowship of the German Research Foundation (DFG; SCHI 985/1-1). We thank numerous individuals on the project for their help in collecting data and data management including Gale Pearce, Lindsey Bloor, Candice Daniels, Melissa Hawkins, Nancy Henry, Kelly Ko, Kelly Glazer-Baron, Shelly Montgomery, Chrisana Olson, and Jane Gilbert. We also thank the couples who graciously agreed to participate in the study. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Cynthia A. Berg, Department of Psychology, University of Utah, 380 S. 1530 E. Room 502, Salt Lake City, UT 84112. E-mail: Cynthia.berg@ psych.utah.edu 167 BERG, SCHINDLER, SMITH, SKINNER, AND BEVERIDGE 168 ment as separable functions of collaboration and whether these functions related to relevant constructs that define their function (i.e., cognitive compensation related to cognitive performance and interpersonal enjoyment to marital satisfaction). Age differences were examined in these functions. We expected that adults would perceive collaboration as serving a cognitive and interpersonal function, and that older adults would endorse both functions more frequently than would middle-aged adults. In addition, the cognitive function was expected to relate to husbands’ and wives’ actual cognitive abilities more so for older adults and the interpersonal function to marital satisfaction more so for older adults. We also examined whether both cognitive compensation and interpersonal enjoyment functions figure into perceptions of the frequency of collaboration in daily life and spousal perceptions while performing a collaborative task. The perceived frequency of collaboration was hypothesized to relate to both the cognitive compensation and interpersonal enjoyment functions. Finally, the interpersonal function was thought to relate to couples’ perceptions of the affiliative nature of their spouse’s behavior in a collaborative task. Methods Participants Participants were 146 middle-aged (Wives: M ⫽ 43.9 years old, SD ⫽ 3.8, range 32–54 years; Husbands: M ⫽ 45.8 years old, SD ⫽ 4.0, range 37–59 years) and 154 older married couples (Wives: M ⫽ 62.2 years old, SD ⫽ 4.5, range 50 –71 years; Husbands: M ⫽ 64.7 years old, SD ⫽ 4.3, range 52–76 years). The sample was largely Caucasian (Wives 95%, Husbands 96.3%) and from the greater Salt Lake City area. On average, middle-aged couples had been married for 18.5 years (SD ⫽ 6.2, range 5–31) and older couples for 36.4 years (SD ⫽ 10.2, range 5–53).1 This was the first marriage for 79.5% of middle-aged women and 84.9% of middle-aged men and for 76.0% of older women and 76.0% of older men. Couple eligibility included: 1) married for a minimum of 5 years; 2) at least one spouse was either between 40 and 50 years old or between 60 and 70 years old; 3) no more than a 10-year age difference between spouses; 4) were not currently taking heart or blood pressure medications from a selected list (primarily Beta-Blockers, Calcium-Blockers, and Antianginals); 5) body mass index (BMI) of 38 or less; and 6) had English as their primary language (see Berg et al., 2007 for additional details). Procedure Participants were recruited through a survey company, advertisements in newspapers, and flyers and presentations at community programs. The questionnaires analyzed here represent a subset of those included in the study. No overlap exists between this paper and other papers based on this dataset. Spouses first completed the Perceptions of Collaboration and Marital Satisfaction measures independently and then took part in a laboratory session including the errand running task. In a second laboratory session the cognitive tasks were administered. Measures Perceptions of collaboration questionnaire (PCQ). This 9-item measure assessed wives’ and husbands’ perceptions of collaboration when solving everyday problems and making decisions on 5-point scales (higher scores indicate stronger agreement). Based on confirmatory factor analyses (see Results Section), we averaged three items per construct to form three subscales. Cognitive Compensation (C; ␣Wives ⫽ .57; ␣Husbands ⫽ .61) consisted of “I make better decisions when my spouse and I work together,” “I view working together with my spouse as necessary as it is harder for me to do things by myself,” and “Working together with my spouse is useful as he/she makes up for things that I don’t do well.” Interpersonal Enjoyment (E; ␣Wives ⫽ .59; ␣Husbands ⫽ .65) consisted of “I enjoy the support and encouragement I receive when I work together with my spouse,” “Solving everyday problems and making decisions together with my spouse brings us closer together,” and “I dislike getting my spouse’s assistance on everyday tasks as it makes me feel incompetent” (reverse scored). Finally, frequency (F; ␣Wives ⫽ .80; ␣Husbands ⫽ .70) of collaboration was measured by “My spouse and I always work together to deal with really important household decisions,” “Nearly everyday my spouse and I work together to make everyday decisions,” and “It is rare for my spouse and I to share tasks and make decisions together” (reverse scored). Cognitive measures. Participants completed individually 7 tasks in small groups (see Ko, Berg, Uchino, & Smith, 2007). We focused on age-sensitive measures of fluid intelligence: Letter and Pattern Comparison tests of perceptual speed (Salthouse, 1996; Salthouse & Meinz, 1995) and the PMA Spatial Relations and Letters Series tests (Thurstone, 1962). Analyses supported that the tests loaded on a single fluid intelligence factor (see Ko et al., 2007). Marital satisfaction was assessed with the Marital Adjustment Test (Locke & Wallace, 1959), a reliable and valid measure of marital adjustment (␣ ⫽ .73 for husband, .76 for wives). Spousal affiliation in an errand running task. Couples planned a morning of running 13 errands (see Berg et al., 2007). The Impact Message Inventory (IMI: Schmidt, Wagner, & Kiesler, 1999) assessed participants’ perceptions of their spouse’s behavior during the task. The IMI was a 32-item abbreviated version of the original inventory; we focus in the present paper on affiliation (friendliness vs. hostility). See Henry et al. (2007) for scoring and reliability. Analysis Plan To account for the dependencies between husbands and wives we analyzed the data at a dyadic level. We established the threefactor structure of the PCQ through confirmatory factor analysis 1 Because of age differences between husbands and wives, some of the husbands and wives were slightly out of the age range for their age group (2 women and 17 men were over 50 but their spouse was in the age range of the middle-aged group, 39 women and 9 husbands were under 60 but their spouse was in the older age group). For most of the cases the spouse was only 1 or 2 years away from the age cut-off (e.g., wife was 59 but husband was 60 –70). Analyses were rerun with these cases removed to ascertain the effect on results. All results remained the same with one exception. For the analyses predicting perceptions of cognitive compensation, for wives, the effect of husbands’ fluid intelligence was significant with wives perceiving greater cognitive compensation when their husband scored higher on fluid intelligence. PERCEPTIONS OF COLLABORATION (CFA), modeling three factors for each spouse in one analysis and testing for factorial invariance between age groups and across husbands and wives. PCQ factors and residual variances of corresponding PCQ items were allowed to correlate between husbands and wives. Second, to test associations of the functions of collaboration with cognition, marital satisfaction, frequency, and affiliation in the errand task, we conducted multivariate hierarchical linear modeling with application to matched pairs (HMLM2; Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2000). These analyses simultaneously estimated models for husbands and wives and tested for differences in regression weights across husband and wife (see Berg et al., 2007). Results Dimensions of Collaboration: Confirmatory Factor Analysis We established the three-factor structure of the PCQ in both husbands and wives through CFA. First, we compared the hypothesized six-factor model (three factors per spouse; 2 ⫽ 357.86, df ⫽ 234, CFI ⫽ .92, TLI ⫽ .90, RMSEA ⫽ .06, SRMR ⫽ .06) to an alternative two-factor model (one overall collaboration factor per spouse; 2 ⫽ 500.39, df ⫽ 272, CFI ⫽ .85, TLI ⫽ .84, RMSEA ⫽ .08, SRMR ⫽ .08) and found that the six-factor model fit the data much better, 2(38) ⫽ 142.53, p ⬍ .001. Second, we tested for metric factorial invariance between middle-aged and older individuals by constraining factor loadings for middle-aged and older wives to be equal and factor loadings for middle-aged and older husbands to be equal. Adding this constraint did not change the model fit, 2(12) ⫽ 12.17, ns. Third, we tested for factorial invariance by constraining factor loadings to be equal for wives and husbands, which did not change the model fit, 2(6) ⫽ 6.45, ns. Thus, our analyses confirmed that the selected PCQ items have the same factor structure in middle-aged and older couples and in wives and husbands, which justified forming three PCQ scales for each spouse. Considering the complexity of the model, the fit was adequate (2 ⫽ 376.48, df ⫽ 252, CFI ⫽ .92, TLI ⫽ .90, RMSEA ⫽ .06, SRMR ⫽ .08).2 The variances of the six factors did not differ significantly between age groups nor did any of the factor covariances. Age differences were found in the factor means with older husbands compared to middle-aged husbands reporting collaborating more for compensation, enjoying collaboration more, and collaborating more frequently than middle-aged husbands as indicated by estimated factor means significantly different from zero (z ⫽ 2.3, 4.3, and 3.0, respectively, ps ⬍ .01; factor means for middle-aged spouses were constrained to zero in the CFA to form a comparison group). The same pattern emerged for older wives, who reported greater enjoyment of collaboration (z ⫽ 2.0, p ⬍ .05), with factor means for compensation and frequency marginally higher in old as compared to middle-aged wives (z ⫽ 1.9 and 1.9, ps ⬍ .10). Predicting Compensation From Cognition and Enjoyment From Marital Satisfaction To examine the relationships of cognitive ability with cognitive compensation and of marital satisfaction with interpersonal enjoy- 169 ment, two HMLM models were constructed. Husbands’ and wives’ perceptions of collaboration as compensation were predicted from five variables: age group (effect coded ⫺1 ⫽ middleaged, 1 ⫽ older), own and spouse’s fluid intelligence (centered at its mean separately for husbands and wives), and the interactions of age group with own and spouse’s fluid intelligence (Aiken & West, 1991). For husbands’ reports of compensation no significant effects were found when controlling for age. For wives a significant interaction was found between age group and own cognitive function [b ⫽ ⫺.14, standard error (SE) ⫽.05, p ⬍ .01, effect size ⫽ .013]. Simple slopes analyses (conducted with Preacher, Curran, & Bauer’s, 2003, online calculator) revealed that for older women lower fluid intelligence was associated with greater perceptions that collaboration served a compensatory function [t(274) ⫽ ⫺2.14, p ⬍ .05], whereas for middle-aged women there was no significant slope between fluid intelligence and compensation (see Figure 1). The interaction effect of age and wives’ fluid intelligence was not significant for husbands’ perceptions of compensation and the test of the significance of the difference between wives’ and husbands’ coefficients was significant, 2(1) ⫽ 13.03, p ⬍ .01. A similar model including five independent variables was conducted to predict husbands’ and wives’ enjoyment of collaboration from marital satisfaction and age group. Husbands’ marital satisfaction was predictive of his enjoyment (b ⫽ .31, SE ⫽ .04, p ⬍ .01, effect size ⫽ .09) and wives’ satisfaction was predictive of her enjoyment (b ⫽ .28, SE ⫽ .04, p ⬍ .01, effect size ⫽ .06). No spouse effects on own enjoyment or interactions of age group ⫻ satisfaction were found. Cognitive and Interpersonal Functions Predicting Frequency To test whether these functions predicted the perceived frequency of collaboration, a similar HMLM was used. Husbands’ and wives’ perceptions of collaboration frequency were predicted from ten independent variables: age group, husband and wife report of cognitive compensation and interpersonal enjoyment, the interactions of age group with each reporter’s view of compensation and enjoyment, and own marital satisfaction as a control variable (as it was important in understanding enjoyment). For husbands, greater husband marital satisfaction (b ⫽ .20, SE ⫽ .04, p ⬍ .01, effect size ⫽ .05), husband views of compensation (b ⫽ .13, SE ⫽ .04, p ⬍ .01, effect size ⫽ .02) and husband views of interpersonal enjoyment (b ⫽ .19, SE ⫽ .04, p ⬍ .01, effect size ⫽ .03) were associated with greater frequency of collaboration. Wives’ reports of collaboration frequency were predicted by her own views of marital satisfaction (b ⫽ .39, SE ⫽ .04, p ⬍ .01, effect size ⫽ .08), cognitive compensation (b ⫽ .16, SE ⫽ .04, p ⬍ .01, effect size ⫽ .02), and enjoyment (b ⫽ .19, SE ⫽ .04, p ⬍ .01, effect size ⫽ .02). 2 Details regarding the SEM analyses including parameter estimates for the CFA can be found in the appendix, which is available online as supplemental material. 3 We utilized the Pseudo-R2 method recommended by Raudenbush and Bryk (2002) to estimate effect sizes. BERG, SCHINDLER, SMITH, SKINNER, AND BEVERIDGE 170 4.4 Wife's Compensation 4.2 4 Middle-Aged Older 3.8 3.6 3.4 3.2 L ow High Wife's Fluid Intelligence Figure 1. Wives’ perceptions of cognitive compensation as a function of age and wives’ fluid intelligence. Cognitive and Interpersonal Functions and Couples’ Affiliation Within a Collaborative Setting A final HMLM analysis including ten independent variables examined whether compensation and enjoyment were predictive of husbands’ and wives’ perceptions of their spouse’s affiliation while interacting in the errand running task (when also considering age group and marital satisfaction). For husbands, when he reported greater marital satisfaction (b ⫽ .41, SE ⫽ .10, p ⬍ .01, effect size ⫽ .02) and interpersonal enjoyment from collaboration (b ⫽ .23, SE ⫽ .10, p ⬍ .05, effect size ⫽ .003) he also perceived his wife as more affiliative in the interaction. In addition, a significant age group ⫻ wife compensation interaction (b ⫽ .19, SE ⫽ .09, p ⬍ .05, effect size ⫽ .002) revealed that when older wives perceived greater compensation husbands viewed wives as more affiliative [simple slopes for older wives t(274) ⫽ 2.79, p ⬍ .01), see Figure 2]. For wives, similarly a significant age group x wife compensation interaction (b ⫽ .21, SE ⫽ .09, p ⬍ .05, effect size ⫽ .0004) revealed that when older wives perceived greater compensation, wives viewed husbands as more affiliative [simple slopes for older wives, t(274) ⫽ 2.73, p ⬍ .01, see Figure 2]. Wives perceived their spouse as more affiliative when she reported greater marital satisfaction (b ⫽ .50, SE ⫽ .10, p ⬍ .01, effect size ⫽ .03) and when she reported greater enjoyment from collaboration (b ⫽ .34, SE ⫽ .10, p ⬍ .01, effect size ⫽ .007). Discussion Adults in midlife and later adulthood perceived that collaboration serves an interpersonal function that is separate from its cognitive compensation function with age differences such that older men especially perceived that collaboration served more of a compensation and enjoyment function and reported more frequent use of collaboration (the trend was similar for women). Greater perceived cognitive compensation through collaboration was related to lower cognitive ability only for older wives. The interpersonal enjoyment function was related to greater marital satisfaction for both husbands and wives similarly across age. These two functions related to greater reported frequency of collaboration to solve everyday problems. Finally, analyses within a specific collaborative task revealed that cognitive compensation and especially interpersonal enjoyment were associated with greater perceptions of affiliation of one’s spouse. Cognitive and Interpersonal Functions of Collaboration Consistent with collaboration serving a compensation function for older adults (Dixon & Gould, 1996; Meegan & Berg, 2002), results revealed that older husbands endorsed the cognitive compensation and interpersonal enjoyment function and reported using collaboration more frequently than did middle-aged husbands (older wives reported more enjoyment but only tended in the same direction for compensation and frequency). The functions of collaboration and its frequency were strongly endorsed (means of around 4 on a 5-point scale), however, by both age groups. The age differences in compensation and enjoyment did not remain once cognitive ability and marital satisfaction (both associated with age) were controlled. These results are only somewhat consistent with the view in the collaboration literature that its use derives from the need to compensate for cognitive function (Dixon & Gould, 1996). The link between perceptions of compensation and lower fluid intelligence was present only among older wives, suggesting that they may be more in tune with their need for collaboration. In addition to the cognitive function of collaboration, adults perceived an interpersonal enjoyment function, which was enhanced in marriages of higher quality. The interpersonal function of collaboration has been neglected in the literature, which focuses nearly exclusively on its role in optimizing (Rogoff, 1998) or compensating for cognitive function (Dixon & Gould, 1996). In close interpersonal relationships such as long-term marriage, collaboration has been described by couples as a key factor in what defines their marriage (Berg et al., 2003). Making PERCEPTIONS OF COLLABORATION 171 4.4 Husband's View of Wife's Affiliation 4.2 4 3.8 Middle-Aged Older 3.6 3.4 3.2 3 Low High Wife's View of Compensation Wife's View of Husband s Affiliation 4.4 4.2 4 3.8 Middle-Aged Older 3.6 3.4 3.2 3 Low High Wife's View of Compensation Figure 2. Husbands’ and wives’ perceptions of spouse’s affiliation in collaborative task as a function of age and wife’s compensation. everyday decisions (regarding finances, health, and home repair) as well as solving everyday problems (e.g., household chores) may build a sense of the couple as a unit (Badr & Acitelli, 2005) and may contribute to and be a reflection of that marital satisfaction. Cognitive and Interpersonal Functions and Frequency of Collaboration The perceived frequency of collaboration in couples’ daily lives was predicted from both the cognitive compensation and interpersonal functions and these relationships did not differ by age. For both husbands and wives, perceptions of the frequency of use of collaboration were associated with their own interpersonal enjoyment of collaboration and views of cognitive compensation. These results strengthen the view that the frequency of collaboration is greater when spouses enjoy collaboration at an interpersonal level, consistent with the importance of marital satisfaction in the use of dyadic coping (Hagedoorn et al., 2000). The fact that only one’s own perceptions of collaboration as cognitive compensation were associated with frequency suggest that the frequency with which collaboration occurs may be driven more by one’s own need for compensation, rather than a dyadic need. These functions of collaboration were reflected in individuals’ perceptions of their spouse’s affiliative behavior as couples collaborated, providing a window into how these functions operate within actual collaborative settings. Perceptions of interpersonal enjoyment were associated with greater perceptions that one’s spouse was warm and affiliative and these effects were over and above the effect of marital satisfaction. As a whole the results revealed several links among interpersonal enjoyment and marital satisfaction, couples’ perceptions of the frequency of collaboration, and affiliation in the errand task. The results are consistent with a process whereby greater marital satisfaction may be re- BERG, SCHINDLER, SMITH, SKINNER, AND BEVERIDGE 172 flected in greater enjoyment and more proximally in perceptions of affiliation in collaborative interaction. These warm and affiliative interactions may contribute to subsequent enhancements in interpersonal enjoyment and marital satisfaction. For husbands’ and wives’ perceptions of each others’ affiliative behavior, greater wives’ cognitive compensation was associated with greater perceptions of affiliative behavior. These results suggest that when older wives perceive greater cognitive need for collaboration, spouses’ behavior may be perceived as more loving, which could be due to perceptions of the interaction driven by her greater need or to the altered nature of the interaction (e.g., more of a teaching or scaffolding interaction for husbands). Such results may be restricted to a somewhat normal range of cognitive ability and may not hold when spouses experience extreme need for compensation such as in the case of mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. The results should be considered together with their limitations. The relatively young age of our older adult group may have restricted relationships between cognitive ability and cognitive compensation. Although our previous work indicates that older adults differed from middle-aged adults in cognitive ability (Berg et al., 2007), our older adult group was in their 60s, now considered a young-old sample (Baltes & Smith, 2003). Research with adults of more advanced age who are experiencing greater limits in cognition will be useful in clarifying relationships between cognition and cognitive compensation. Our results are limited by our largely Caucasian sample. Collaboration may be more frequent and serve interpersonal functions in cultures that are more interdependent (Latino, Asian; Berg & Upchurch, 2007). The results are limited, somewhat, by the relative shortness of the PCQ, which likely resulted in the low reliability of some subscales. Additional work is in progress to improve the measure’s reliability. The cross-sectional nature of our data cannot address directions of effects between marital satisfaction, cognitive ability, and the cognitive and interpersonal functions of collaboration. These relationships are likely dynamic and transactional such that the interpersonal function both derives from high marital satisfaction, provides a lens through which interactions are viewed in collaboration, and enhances subsequent marital satisfaction. In addition to the cognitive compensation function of collaboration that is so frequently emphasized in the aging literature, collaboration has an important interpersonal component that may derive from the overall quality of the relationship as well as affect the frequency of collaboration. Both functions are involved in the perceived frequency of collaboration during middle-aged and older adulthood and in how it is experienced in collaborative tasks. Greater attention to the interpersonal enjoyment function may facilitate collaboration’s use in daily decision making and solving everyday problems (Strough, Cheng, & Swenson, 2002). References Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Badr, H., & Acitelli, L. K. (2005). Dyadic adjustment in chronic illness: Does relationship talk matter? Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 465– 469. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.465 Baltes, P. B., & Smith, J. (2003). New frontiers in the future of aging: From successful aging of the young old to the dilemmas of the fourth age. Gerontology, 49, 123–135. doi:10.1159/000067946 Berg, C. A., Johnson, M. M. S., Meegan, S. P., & Strough, J. (2003). Collaborative problem-solving interaction in young and old married couples. Discourse Processes, 35, 33–58. doi:10.1207/S15326950DP3501_2 Berg, C. A., Smith, T. W., Ko, K., Beveridge, R., Story, N., Henry, N., . . . Glazer, K. (2007). Task control and cognitive abilities of self and spouse in collaboration in middle-aged and older couples. Psychology and Aging, 22, 420 – 427. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.420 Berg, C. A., & Upchurch, R. (2007). A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 920 –954. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.920 Berg, C. A., Wiebe, D. J., Bloor, L., Butner, J., Bradstreet, C., Upchurch, R., . . . Patton, G. (2008). Collaborative coping and daily mood in couples dealing with prostate cancer. Psychology and Aging, 23, 505– 516. doi:10.1037/a0012687 Beveridge, R. M., & Berg, C. A. (2007). Parent-adolescent collaboration: An interpersonal model for understanding optimal interactions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 10, 25–52. doi:10.1007/s10567006-0015-z Carstensen, L. L., & Mikels, J. A. (2005). At the intersection of emotion and cognition: Aging and the positivity effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 117–121. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005 .00348.x Dixon, R. A., & Gould, O. N. (1996). Adults telling and retelling stories collaboratively. In P. B. Baltes & U. M. Staudinger (Eds.), Interactive minds: Life-span perspectives on the social foundation of cognition (pp. 221–241). New York: Cambridge University Press. Hagedoorn, M., Kuijer, R. G., Buunk, B. P., DeJong, G. M., Wobbes, T., & Sanderman, R. (2000). Marital satisfaction in patients with cancer: Does support from intimate partners benefit those who need it the most? Health Psychology, 19, 274 –282. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.19.3.274 Henry, N. J., Berg, C. A., Smith, T. W., & Florsheim, P. (2007). Positive and negative relationship characteristics and their association with marital satisfaction in middle-aged and older couples. Psychology and Aging, 22, 428 – 441. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.428 Johansson, O., Andersson, J., & Ronnberg, J. (2000). Do elderly couples have a better prospective memory than other elderly people when they collaborate? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 14, 121–133. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0720(200003/04)14:2⬍121::AID-ACP626⬎ 3.0.CO;2-A Ko, K. J., Berg, C. A., Uchino, B., & Smith, T. W. (2007). Profiles of successful aging in middle-aged and older married couples. Psychology and Aging, 22, 705–718. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.22.4.705 Locke, H. J., & Wallace, K. M. (1959). Short marital-adjustment and prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage and Family Living, 21, 251–255. doi:10.2307/348022 Martin, M., & Wight, M. (2008). Dyadic cognition in old age: Paradigms, findings, and directions. In S. M. Hofer & D. F. Alwin (Eds.), Handbook of cognitive aging: Interdisciplinary Perspectives (pp. 629 – 646). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Meegan, S. P., & Berg, C. A. (2002). Contexts, functions, forms, and processes of collaborative everyday problem solving in older adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26, 6 –15. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000283 Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2003). Simple intercepts, simple sloes, and regions of significance in MLR 2-Way Interactions. http://people.ku.edu/⬃preacher/interact/mlr2.htm Raudenbush, S., & Bryk, A. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Raudenbush, S., Bryk, A., Cheong, Y. F., & Congdon, R. (2000). HLM5: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: SSI. Rogoff, B. (1998). Cognition as a collaborative process. In W. Damon PERCEPTIONS OF COLLABORATION (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Volume 2: Cognition, perception, and language. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Salthouse, T. A. (1996). General and specific speed mediation of adult age differences in memory. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences, 51, P30 –P42. Salthouse, T. A., & Meinz, E. J. (1995). Aging, inhibition, working memory, and speed. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Science, 50, P297–P306. Schmidt, J. A., Wagner, C. C., & Kiesler, D. J. (1999). Psychometric and circumplex properties of the octant scale Impact Message Inventory (IMI-C): A structural evaluation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46, 325–334. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.46.3.325 Story, T. N., Berg, C. A., Smith, T. W., Beveridge, R., Henry, N. J. M., & Pearce, G. (2007). Age, marital satisfaction, and optimism as predictors of positive sentiment override in middle-aged and older married couples. Psychology and Aging, 22, 719 –727. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.22.4.719 173 Strough, J., Cheng, S., & Swenson, L. M. (2002). Preferences for collaborative and individual everyday problem solving in later adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26, 26 –35. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000337 Strough, J., & Margrett, J. (Eds.). (2002). Overview of the special section on collaborative cognition in later adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26, 2–59. Thurstone, T. G. (1962). Primary mental abilities: Grades 9 –12, 1962 revision. Chicago: Science Research Associates. Received September 4, 2009 Revision received July 23, 2010 Accepted August 6, 2010 䡲 Members of Underrepresented Groups: Reviewers for Journal Manuscripts Wanted If you are interested in reviewing manuscripts for APA journals, the APA Publications and Communications Board would like to invite your participation. Manuscript reviewers are vital to the publications process. As a reviewer, you would gain valuable experience in publishing. The P&C Board is particularly interested in encouraging members of underrepresented groups to participate more in this process. If you are interested in reviewing manuscripts, please write APA Journals at Reviewers@apa.org. Please note the following important points: • To be selected as a reviewer, you must have published articles in peer-reviewed journals. The experience of publishing provides a reviewer with the basis for preparing a thorough, objective review. • To be selected, it is critical to be a regular reader of the five to six empirical journals that are most central to the area or journal for which you would like to review. Current knowledge of recently published research provides a reviewer with the knowledge base to evaluate a new submission within the context of existing research. • To select the appropriate reviewers for each manuscript, the editor needs detailed information. Please include with your letter your vita. In the letter, please identify which APA journal(s) you are interested in, and describe your area of expertise. Be as specific as possible. For example, “social psychology” is not sufficient—you would need to specify “social cognition” or “attitude change” as well. • Reviewing a manuscript takes time (1– 4 hours per manuscript reviewed). If you are selected to review a manuscript, be prepared to invest the necessary time to evaluate the manuscript thoroughly.