+

advertisement

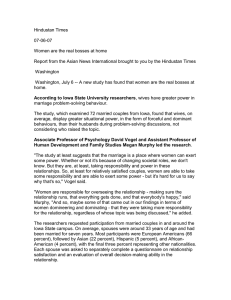

Behavioural Science Section / Dyadic Interrelations in Lifespan Development and Aging: How Does 1 + 1 Make a Couple? Published online: July 8, 2010 Gerontology 2011;57:167–172 DOI: 10.1159/000318642 Affect Covariation in Marital Couples Dealing with Stressors Surrounding Prostate Cancer Cynthia A. Berg a Deborah J. Wiebe b Jonathan Butner a a Department of Psychology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, and b Division of Psychology, Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Tex., USA Key Words Marital couples ⴢ Dyadic coping ⴢ Affect covariation ⴢ Diary methods ⴢ Older couples ⴢ Prostate cancer Abstract Background: Consistent with a dyadic perspective to coping with chronic illness, couples may experience covariation in their daily affective experiences, particularly as they deal with stressful events surrounding chronic illness, such as prostate cancer. Objective: Our purpose was to examine the daily covariation of negative and positive affect among husbands and wives and whether this covariation was enhanced when couples mentioned the same stressful event and reported frequently collaborating. Methods: Fifty-nine husbands diagnosed as having prostate cancer and their wives participated in a daily diary where they reported on the most stressful event of the day, positive and negative affect, coping strategies and whether their spouse was involved in a collaborative manner. Coders independently made judgments as to whether the stressful event mentioned by husbands and wives was the same. Results: Multivariate hierarchical linear models revealed that on days when wives experienced greater negative affect, husbands did so as well. However, negative affect covariation was only found when © 2010 S. Karger AG, Basel 0304–324X/11/0572–0167$38.00/0 Fax +41 61 306 12 34 E-Mail karger@karger.ch www.karger.com Accessible online at: www.karger.com/ger spouses mentioned the same daily stressful event. The mean levels of collaborative coping across the 14 days moderated this negative covariation effect for wives, such that negative affect covariation was enhanced when wives reported collaborating more frequently. Positive affect covariation was not found. Conclusion: The results reveal that negative affect covariation may be most likely when spouses experience similar stressors and wives perceive frequently collaborating. Partners within close relationships experience similar negative affect as their spouse, pointing to the shared nature of illness in late life. Copyright © 2010 S. Karger AG, Basel Older adulthood is marked by the increased incidence of chronic illnesses [1] that have consequences for affective well-being [2]. Chronic illnesses may not only influence the affective experience of those with illness, but within the marriage also their spouses, who may share the illness experience [3, 4]. Evidence for covariation in negative affect can be found in the literature. For example, the depressive symptoms of elders experiencing illness such as vision loss, end-stage renal disease and arthritis are associated with the spouse’s depressive symptoms measured at one point in time [5], across Cynthia A. Berg Department of Psychology, University of Utah 380 S. 1530 E. Salt Lake City, UT 84112 (USA) Tel. +1 801 581 5380, Fax +1 801 581 5841, E-Mail cynthia.berg @ psych.utah.edu multiple points in time and also change at similar rates over time [6, 7]. However, the meta-analysis by Hagedoorn et al. [8] suggests that negative affect covariation among spouses with cancer is modest, with large heterogeneity, indicating that there may be moderators of affect covariation. The affective experience of spouses may also covary on a more daily basis as individuals cope with stressors surrounding illness. That is, spouses may covary in their day-to-day increases or decreases in negative and positive affect [9]. Such covariation may be indicative of emotional contagion or emotional transmission as one spouse’s affective experience spills over to the other spouse’s experience by virtue of their close proximity [10, 11]. In couples experiencing an illness like prostate cancer, affective covariation may reflect their shared experience of daily stressful events and their engagement in coping with those events. Prostate cancer and its treatment involves numerous stressful events (e.g. incontinence and impotence) that affect not only the patient but the spouse as well [12]. Daily affective covariation may be especially salient as spouses report similar stressful events on a daily basis and engage in collaborative attempts to cope with the stressful event. We examined whether affect covariation might be enhanced when couples work closely together surrounding daily stressful events. On a daily basis, spouses may experience similar stressful events and these events may create a context whereby spouses work collaboratively in coping with the event. Within the dyadic coping literature, collaborative coping entails active discussions about both problem solving and emotions and anxieties relevant to stressful events [3, 13], and as such may be associated with greater negative affect covariation. Couples who collaborate frequently may experience more affective covariation in both positive and negative affect as they have more opportunities for transmission or contagion to occur. The present study had 2 aims: (1) to examine the daily affect covariation in negative and positive affect in couples as they dealt with daily stressors surrounding prostate cancer and (2) to examine whether affect covariation was enhanced when couples mentioned the same daily stressor and reported collaborating on a frequent basis. We predicted that affect covariation would occur for both negative and positive affect and that negative affect covariation would be higher in couples who report the same daily stressor and who collaborate frequently to deal with stressful events. 168 Gerontology 2011;57:167–172 Methods Participants Fifty-nine men diagnosed as having localized prostate cancer (stage I) and their spouses participated in the study. The men were 40–84 years of age [M = 67.56, standard deviation (SD) = 9.16] and were largely in long-term marriages (M = 38.4, SD = 13.7, range = 1–59 years). The participants were mostly Caucasian (94.7%), retired (67.8% men, 78% women) and had some education beyond high school (82.8% men; 64.4% women). The wives were 38–80 years of age (M = 64.8, SD = 9.2). Out of 102 eligible men approached, 73 (72% of the eligible pool) initially agreed to participate, but 59 completed all components of the study. Nine couples withdrew before any data collection, and another 5 withdrew after completing the baseline questionnaires. The participants most frequently mentioned an illness in the family as a reason for not completing the study. Men and their wives were recruited from oncology, radiation therapy and surgical clinics (93%), and through prostate cancer support group publications (7%). Couples were eligible if the husband had been diagnosed as having localized prostate cancer (i.e. cancer had not spread beyond the prostate gland) and was in the process of making a decision about 1 or more phases of treatment; 89% of the participants were recruited during treatment consultations. The average number of days since diagnosis of prostate cancer was 83.4 (range = 1–498, SD = 106), with 90% recruited within 6 months of diagnosis. (See [13] regarding additional details concerning sample characteristics.) Individuals were excluded if they had a history of cancer other than skin cancer, did not speak English and did not have a significant other. Procedure The study consisted of 3 components. First, husbands and wives were asked to complete take-home packets separately. Second, approximately 1–2 weeks after initial recruitment, a 1.5hour in-home session occurred where take-home packets were collected and reviewed and other measures not relevant to the present paper were completed. Third, the couples completed paper diaries individually for 14 consecutive days, implementing the following procedures that limit the shortcomings of paper diaries [14]. The couples were called on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11 and 13 during the daily diary component of the study as a reminder to complete their diaries and ask if they had any questions or concerns. The participants returned each individual diary separately in self-addressed stamped envelopes, which were reviewed by research assistants for postmarked dates and missing data. The couples received USD 38 for completing the questionnaires and home interview, and USD 112 for completing the entire diary. Measures Background Information. The participants separately provided background information (73% of the men and 78% of the women reported 2 or more medical conditions). Diary. The daily paper diary assessed aspects of dyadic coping (see [13] for more details). At the end of each day the husbands and wives first described the most bothersome event of the day dealing with prostate cancer. If the participants did not have a bothersome event dealing with prostate cancer, they reported the most bothersome event of the day. The participants then rat- Berg /Wiebe /Butner ed the extent to which the stressful event was due to prostate cancer on a scale of 1 = not at all to 7 = completely (M = 3.81, SD = 1.89 for husbands, M = 2.97, SD = 1.53 for wives). Fifty-six percent of husbands’ stressors and 47.1% of wives’ stressors dealt with prostate cancer to some degree (rated 2 or above on whether the event was due to prostate cancer [13]). All stressors were used in the present analyses to maximize the available number of days for analysis. The participants were also asked to rate on a 7-point scale (1 = minor annoyance to 7 = stress you would feel upon the death of a friend or family member) how stressful the event was (M = 3.65, SD = 1.42 for husbands, M = 3.76, SD = 1.45 for wives). To assess whether the couples were congruent in mentioning the same stressful events, 2 coders independently made judgments as to whether the stressful event mentioned by husbands and wives was the same (0 = not congruent, 1 = congruent). On average the couples were coded as mentioning the same stressful event on 27% of the days (SD = 22). Reliability was established on 20% of the couples and the coders achieved 83% agreement. To assess daily collaborative coping strategies, the participants were asked to list 3 things that they thought, did or felt to deal with the event and indicated whether their spouse was ‘not involved’, ‘supportive’ (gave advice, listened, changed his/her plans on account of me), ‘worked together’ (worked as a team, negotiated) or ‘took charge’ (told me what to do, controlled my actions) for each coping strategy. Collaborative coping was indexed by computing the proportion of strategies categorized as ‘worked together’ (number of coping responses categorized as collaborative out of 3) each day and then averaging across all days of the diary (for husbands M = 0.22, SD = 0.19; for wives M = 0.30, SD = 0.21). To assess daily positive and negative affect, individuals completed the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Scale [15], rating emotions on a scale of 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely. The sum across positive affect items reported on a daily basis (M = 28.9, SD = 7.03 for husbands and M = 27.66, SD = 6.46 for wives) was greater than total negative affect (M = 16.4, SD = 5.48 for husbands and M = 19.5, SD = 5.98 for wives). Two couples had an unacceptably low number of consecutive days (2 and 0) on which both husbands and wives reported diary data and were removed from the analyses. Twenty-nine couples completed all 14 diary entries on the same consecutive days. Fiftyseven couples had data for 4 or more days with the analyses reported based on an average of 10.5 days for both husbands and wives. We utilized a hierarchical linear model, which interpolates the missing data under the assumption that it is missing at random [16] (see [13] for details). Statistical Analysis The diary design provided up to 14 daily reports of positive and negative affect separately from the husband and wife. To assess the relation between husbands’ and wives’ affect and whether daily congruence in stressful events and overall perceived collaboration moderated these dependencies, hierarchical linear models with application to matched pairs were used ([17, 18], HMLM2 [19]). These analyses simultaneously estimated models for husbands and wives (see [3]). The level 1 equation generates a pair of simultaneous analyses for the husband and wife, predicting their own affect from their partner’s daily affect (group centered), congruence between husband and wife in mention of stressful event and the interaction Affect Covariation in Marital Couples Dealing with Prostate Cancer of affect and congruence. The level 2 equation then utilized the person’s perceived collaboration across the 14 days of the diary as a predictor of the covariation effect for both husbands and wives. Lastly, we allowed for different residuals for husbands and wives. Initial analyses were conducted to examine whether affect covariation was moderated by participant age, no significant effects were found for either husband age or wife age in negative or positive affect covariation (all p values 1 0.10) and thus age was not included in additional models. In addition to these concurrent same-day analyses, we also tested for lagged effects (i.e. whether affect of spouse A on day t predicted the affect of spouse B on day t + 1 controlling for spouse B’s affect on day t). However, no lagged associations were found (p 1 0.30) and thus are not reported. Results Negative Affect Covariation, Congruence in Stressful Events and Collaborative Coping In the primary analyses, we examined whether daily affect covariation existed for all stressful events or only for those that husbands and wives mentioned in common, by examining the interaction of negative affect and congruence in the stressful event of the day. As can be seen from table 1, for both husbands and wives the main effect of affect covariation (when congruence is centered at 0 reflecting that husbands and wives did not mention the same stressful event) was not significant. The interaction between negative affect covariation and congruence, however, was significant for both husbands (pseudo-R 2 = 0.002) and wives (pseudo-R 2 = 0.002). This effect indicated that affect covariation did occur when husbands and wives mentioned the same stressful event on a given day. For wives, there was significant variation in the affect covariation effect, allowing for additional level 2 modeling. To clarify whether collaboration was a potential moderator of affect covariation for wives, we examined whether wives who perceived greater collaboration might experience a stronger negative affect covariation effect. In the level 2 model, wives who reported higher collaborative coping (i.e. wives who on average across the 14 days reported greater versus lesser amounts of collaborative coping) moderated the affect covariation effect. Predicted values were computed from the regression equation reported in table 1 by substituting scores 1 SD above and below the mean for collaborative coping and wives’ negative affect (see fig. 1). The significance of the slope of the 2 lines was tested by first centering the level 2 effect of mean levels of collaboration across days and rerunning the model for 1 SD above and below the grand Gerontology 2011;57:167–172 169 Table 1. Unstandardized coefficients, standard error and variance components of multilevel models examining affect covariation Coefficients Variance Husband Negative affect Day1 Intercept Affect covariation Level 2 collaboration Congruence1 Affect covariation ! congruence Positive affect Day1 Intercept Affect covariation Level 2 collaboration Congruence1 Affect covariation ! congruence Wife Husband 19.45 (0.90)** 0.00 (0.07) 0.93 (0.25)** 24.60** 0.02 0.42 (0.14)** 0.17* 28.25 (0.92)** 0.02 (0.06) 0.39 (0.26) 46.73 0.06** Wife –0.04 (0.04) 0.03 16.45 (0.74)** 0.03 (0.04) 38.42** 0.10* 1.58 0.77 (0.37)* 0.33 (0.10)** 0.29* –0.07 (0.06) 29.16 (0.99)** 0.05 (0.05) –0.07 (0.16) 0.11** 38.89 0.08** 0.35 (0.41) –0.06 (0.10) 1.41 –0.07 (0.20) 0.20 0.14 Figures in parentheses represent standard error. * p ! 0.05; ** p ! 0.01. 1 This effect was not entered differentially for husbands and wives as the variable was the same for husbands and wives. Wife’s negative affect 24 22 20 18 16 14 12 Low collaboration High collaboration Low High Husband’s negative affect Fig. 1. Predicted means for wife’s negative affect from interaction of husband’s negative affect ! wife’s perceptions of collaboration. mean. The slope of the line for high collaboration was significant [b = 0.33, SE = 0.07, t(55) = 4.90, p ! 0.01], whereas the slope of the line for low collaboration was not significant [b = –0.00, SE = 0.08, t(55) = –0.05, p 1 0.80]. This effect indicated that negative affect covariation from husbands to wives occurred in couples where wives perceived high amounts of collaborative coping across the 14 days. 170 Gerontology 2011;57:167–172 Additional analyses were conducted to rule out alternative explanations of the negative affect covariation effect when husbands and wives mentioned the same event. First, to the analyses conducted above we added 2 variables, the extent to which the stressful event was due to prostate cancer for wives and for husbands. These analyses indicated that affect covariation for events that were mentioned by husband and wife remained (p values ! 0.01 for both husbands and wives) and thus the extent to which the stressor was due to prostate cancer was not an explanation of the covariation effect. Second, analyses were conducted to determine whether negative affect covariation was a manifestation of stress spillover from one spouse to the other. An interaction term was calculated, group centering husbands’ ratings of the stressfulness of the event and wives’ ratings of the stressfulness of the event. After controlling for the stressfulness covariation, the effect of affect covariation for events that both husbands and wives mentioned remained for husbands (p ! 0.01) and wives (p ! 0.01). Positive Affect Covariation The model predicting husbands’ and wives’ positive affect did not reveal significant positive affect covariation for either husbands’ or wives’ positive affect, when couples were either congruent or not congruent regarding Berg /Wiebe /Butner the most stressful event. For both husbands and wives, the variance component in the unconditional model was significant. However, collaborative coping did not predict variation in positive affect covariation. Discussion Consistent with previous research examining the contagion or transmission of negative affect [10, 11], husbands’ and wives’ negative affect was associated with their spouse’s negative affect. The daily diary approach used here is consistent with research examining spousal similarity in distress both cross-sectionally and longitudinally [7, 8, 20, 21]. However, negative affect covariation only existed when spouses reported the same stressful event of the day. These results extend the research on the transmission or contagion of negative affect [10, 11] by linking negative affect covariation to specific shared stressful events that the couple experiences. In addition, the results seem to suggest that covariation in positive affect is less likely to occur than covariation in negative affect, especially in couples who are experiencing stressful events surrounding prostate cancer. Positive affect covariation has been found in younger couples who are dealing with more routine daily events [9]. Negative affect covariation occurred only when spouses mentioned the same stressful event of the day and, for wives, when they perceived greater collaboration with their husbands across the 14-day diary. Collaborative coping, where couples engage in discussions regarding problem-solving approaches to dealing with daily stressors, may exacerbate this negative affect covariation for wives. We interpret these results to suggest that one of the potential downsides to collaborative coping for women is that one may bear the brunt of the distress that the spouse is experiencing. Collaborative coping involves active discussion and engagement with one’s partner and may include discussing the spouse’s feelings of distress. These short-term costs of collaboration, however, may be associated with more long-term gains as the active engagement nature of collaborative coping may be associated with long-term relational benefits [22]. Although these results could be interpreted to mean that wives in the caregiving role may be more affected by collaborative coping, the meta-analysis by Hagedoorn et al. [18] suggests that women may experience more negative affect in general surrounding cancer whether they are in the patient or caregiver role. Affect Covariation in Marital Couples Dealing with Prostate Cancer The results should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. The sample of prostate cancer patients and their wives was small and largely Caucasian, with a need to replicate the results in a larger sample. Second, we examined collaborative coping as a between-subjects variable, although we know from other work with this sample that individuals differ in their use of collaborative coping on a daily basis [13]. Additional analyses examining how affect covariation was moderated by daily collaborative coping were not significant when congruence in daily stressors was controlled, although low power to detect these daily associations may have influenced the findings. Third, our analyses revealed concurrent associations between husband and wife affect covariation [23] but not prospective associations (lead-lag associations). The absence of lead-lag associations may suggest a more complex timing of affect coupling relationships that could occur through modeling coupled relationships in rates of change over time [9]. In addition, the timing of such lead-lag relationships may occur across a single day, requiring more time-intensive multiday assessments (although the subject burden of such measures may be prohibitive given participants’ overall levels of distress in dealing with a diagnosis of prostate cancer). Fourth, several aspects of the diary implementation may have affected the results. For instance, concerns with paper diaries and whether they are completed on the day that they are assigned and our inability to assess whether couples adhered to the instructions to complete them individually may have affected the results. Further, refinements in the measurement of daily affect (beyond the Positive and Negative Affect Scale [24]) will be important to apply in measuring daily affect surrounding chronic illness. In addition, further methodological work is needed into the measurement of dyadic coping (beyond categorical assessment) and determining appropriate stems to solicit different forms of dyadic coping (e.g. is giving advice viewed as supportive or controlling). Finally, although we conceptualized the husband as the patient in this study, women were actually reporting a greater number of chronic health conditions than men. Future work is needed to examine the affect regulation process of spouses where both are experiencing symptoms and concerns of their respective chronic illnesses, a likely situation for couples during late adulthood [25]. The results add to the growing literature on the shared or dyadic nature of illness across the life span [3]. Individuals coping with chronic illness deal with daily stressful events within a relational context where they Gerontology 2011;57:167–172 171 are both affected by and affect those with whom they are in close relationships. Further research is needed to understand how the daily experience of illness (its symptoms, stressful events, see [25]) of both the patient and the spouse contribute to the coupled affective experience. Acknowledgments This study was supported by a University of Utah Research Foundation Grant awarded to C. A. B. and D. J. W. We thank the following people for assistance in collecting the data and recruiting participants: Lindsey Bloor, Chet Bradstreet, Heather Phippen, John Hayes, Robert Stephenson, Lillian Nail and Gregory Patton. In addition we wish to thank Malinda Freitag and Monica Forsman for their coding of the stressful events. References 1 Hoffman C, Rice D, Sung HY: Persons with chronic conditions: their prevalence and costs. J Am Med Assoc 1996;276:1473–1479. 2 Piazza JR, Charles ST, Almeida DM: Living with chronic health conditions: age differences in affective well-being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2007;62B:313–321. 3 Berg CA, Upchurch R: A developmentalcontextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychol Bull 2007;133:920–954. 4 Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G: Couples Coping with Stress. Emerging Perspectives on Dyadic Coping. Washington, American Psychological Association, 2005. 5 Goodman CR, Shippy RA: Is it contagious? Affect similarity among spouses. Aging Ment Health 2002;6:266–274. 6 Lam M, Lehman A, Puterman E, DeLongis A: Spouse depression and disease course among persons with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1011–1017. 7 Pruchno R, Wilson-Genderson M, Cartwright F: Self-rated health and depressive symptoms in patients with end-state renal disease and their spouses: a longitudinal dyadic analysis of late-life marriages. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009;64B:212–221. 8 Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tunistra J, Coyne JC: Distress in couples coping with cancer: a meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol Bull 2008;134:1–30. 172 9 Butner J, Diamond LM, Hicks AM: Attachment style and two forms of affect coregulation between romantic partners. Pers Relat 2007;14:431–455. 10 Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL: Emotional Contagion. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1994. 11 Thompson A, Bolger N: Emotional transmission in couples under stress. J Marriage Fam 1999;61:38–48. 12 Couper J, Bloch S, Love A, MacVean M, Duchesne GM, Kissane D: Psychosocial adjustment of female partners of men with prostate cancer: a review of the literature. Psychooncology 2006;15:937–953. 13 Berg CA, Wiebe DJ, Bloor L, Butner J, Bradstreet C, Upchurch R, Hayes J, Stephenson R, Nail L, Patton G: Collaborative coping and daily mood in couples dealing with prostate cancer. Psychol Aging 2008;23:505–516. 14 Green AS, Bolger N, Shrout PE, Rafaeli E, Reis HT: Paper or plastic? Data equivalence in paper and electronic diaries. Psychol Methods 2006;11:87–105. 15 Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A: Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:1063–1070. 16 Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW: Hierarchical Linear Models. Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Thousand Oaks, Sage, 1992. 17 Almeida DM, Kessler RC: Everyday stressors and gender differences in daily distress. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998;75:670–680. Gerontology 2011;57:167–172 18 Raudenbush SW, Brennan RT, Barnett RC: A multivariate hierarchical model for studying psychological change within married couples. J Fam Psychol 1995;9:161–174. 19 Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R: HLM5. Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Lincolnwood, SSI, 2000. 20 Bookwala J, Schulz R: Spousal similarity in subjective well-being: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Psychol Aging 1996; 11: 582– 590. 21 Meyler D, Stimpson JP, Peek MK: Health concordance within couples: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:2297–2310. 22 Hagedoorn M, Kuijer RG, Buunk BP, DeJong GM, Wobbes T, Sanderman R: Marital satisfaction in patients with cancer: does support from intimate partners benefit those who need it the most? Health Psychol 2000; 19: 274–282. 23 Larson RW, Almeida DM: Emotional transmission in the daily lives of families: a new paradigm for studying family process. J Marriage Fam 1999;61:5–20. 24 Cranford JA, Shrout PE, Iida M, Rafaeli E, Yi T, Bolger N: A procedure for evaluating sensitivity to within-person change: can mood measures in diary studies detect change reliably. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2006;32:917–929. 25 Roper SO, Yorgason J: Older adults with diabetes and osteoarthritis and their spouses: effects of activity limitations, marital happiness, and social contacts on partners’ daily mood. Fam Relat 2009;58:460–474. Berg /Wiebe /Butner