Implementing Impaired Driving Countermeasures Putting Research into Action

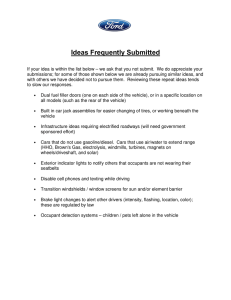

advertisement