Education Efficiency Audit of West Virginia’s Primary and Secondary Education System

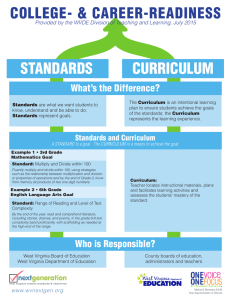

advertisement