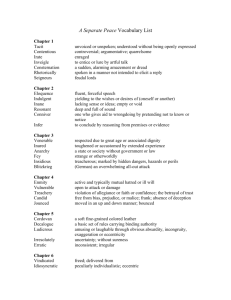

by I

advertisement