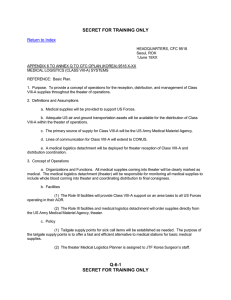

ATTP 4-0.1 Army Theater Distribution May 2011

advertisement