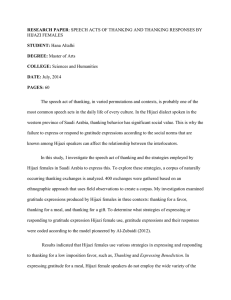

SPEECH ACTS OF THANKING AND THANKING RESPONSES BY HIJAZI FEMALES

advertisement