Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Biological Control

advertisement

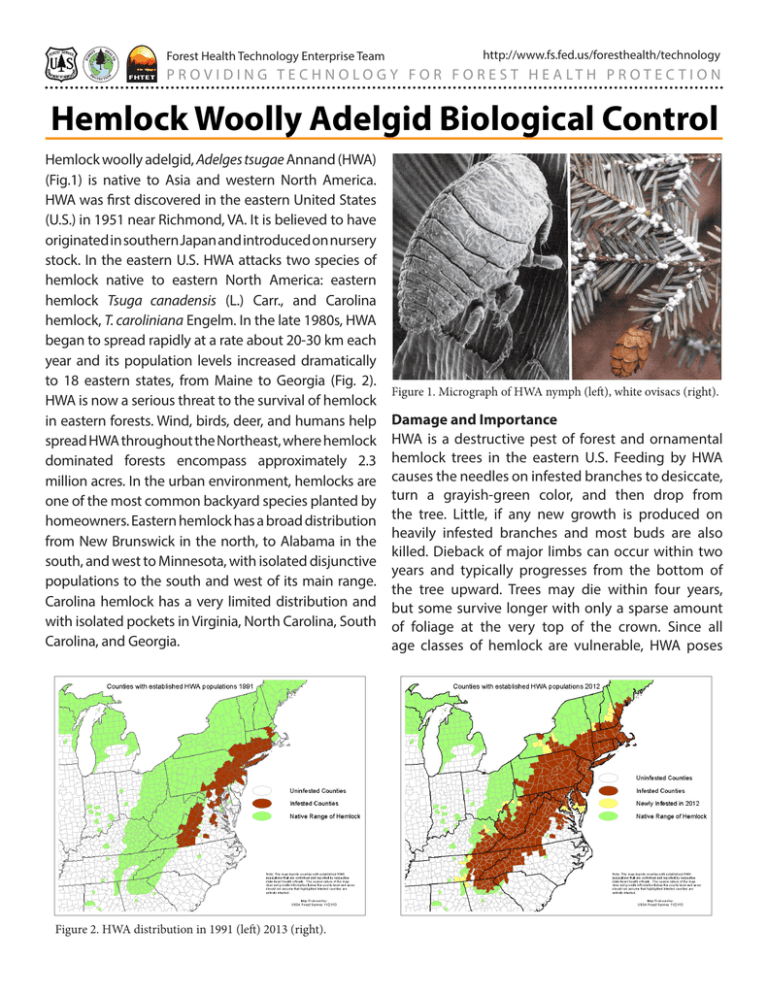

Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology P R O V I D I N G T E C H N O L O G Y F O R F O R E S T H E A LT H P R O T E C T I O N Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Biological Control Hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae Annand (HWA) (Fig.1) is native to Asia and western North America. HWA was first discovered in the eastern United States (U.S.) in 1951 near Richmond, VA. It is believed to have originated in southern Japan and introduced on nursery stock. In the eastern U.S. HWA attacks two species of hemlock native to eastern North America: eastern hemlock Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carr., and Carolina hemlock, T. caroliniana Engelm. In the late 1980s, HWA began to spread rapidly at a rate about 20-30 km each year and its population levels increased dramatically to 18 eastern states, from Maine to Georgia (Fig. 2). HWA is now a serious threat to the survival of hemlock in eastern forests. Wind, birds, deer, and humans help spread HWA throughout the Northeast, where hemlock dominated forests encompass approximately 2.3 million acres. In the urban environment, hemlocks are one of the most common backyard species planted by homeowners. Eastern hemlock has a broad distribution from New Brunswick in the north, to Alabama in the south, and west to Minnesota, with isolated disjunctive populations to the south and west of its main range. Carolina hemlock has a very limited distribution and with isolated pockets in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. Figure 2. HWA distribution in 1991 (left) 2013 (right). Figure 1. Micrograph of HWA nymph (left), white ovisacs (right). Damage and Importance HWA is a destructive pest of forest and ornamental hemlock trees in the eastern U.S. Feeding by HWA causes the needles on infested branches to desiccate, turn a grayish-green color, and then drop from the tree. Little, if any new growth is produced on heavily infested branches and most buds are also killed. Dieback of major limbs can occur within two years and typically progresses from the bottom of the tree upward. Trees may die within four years, but some survive longer with only a sparse amount of foliage at the very top of the crown. Since all age classes of hemlock are vulnerable, HWA poses Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology P R O V I D I N G T E C H N O L O G Y F O R F O R E S T H E A LT H P R O T E C T I O N a significant threat to hemlock health, including the reestablishment of hemlock stands. There are no practical means available to manage HWA in urban and forest situations therefore, long-range management strategies are needed. Biological Control Biological control began in the early 1990s. Surveys in the eastern U.S. indicated that the native natural enemies associated with HWA consisted primarily of generalist predators which did not effectively control HWA populations. In Japan, where HWA is native, it is a common but innocuous inhabitant of forest and ornamental hemlock and spruce. Japanese hemlocks are not significantly injured because of host resistance and natural enemies. For this reason, early efforts since 1996 have focused primarily on the development of a multi-agency biological control program as a method to lessen the destruction by HWA in the eastern U.S. Both Japan and China have been explored for natural enemies. In 2003, a formal HWA initiative was begun by the USDA Forest Service with the development of a 5-year program (2003-2007) to create and implement management options to reduce the spread and impact of HWA. A second 5-year program (2008-2012) was funded to continue and to accelerate the development of research and technology, management, and information transfer. The biological control effort has been greatly expanded with the onset of the HWA Initiative and has involved 28 federal and state agencies, 24 universities, and numerous private industries in the U.S., as well as, 7 institutions in China and Japan. Since no known parasitoids are associated with the Adelgidae, the biological control program for HWA has focused on prey-specific predator species collected from East Asia and the Pacific Northwest of the U.S., as well as entomopathogens. The most widely released predator has been a ladybeetle, Sasajiscymnus (=Pseudoscymnus) tsugae. It was discovered in early 1990s in Japan. Since the first release of adults in Connecticut in 1995, 2.5 million adults were released into 15 states from the southern Appalachians to Maine at more than 400 sites. Although populations have established at a number of sites, post-release recoveries of S. tsugae have been sporadic and usually at low numbers. Recent recoveries of S. tsugae in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park were associated with the oldest release sites, suggesting that this predator may take 5-7 years or more to reach detectable levels in the landscape. If this is true, many hemlock stands in the southern Appalachians may become infested, decline, and die before S. tsugae populations can begin to have an impact, which may already be occurring in some areas of the southern Appalachians. Over 30 generations of S. tsugae ladybeetles have been lab reared from the original genetic stock and released. A new genetic stock of S. tsugae was recently collected in Japan and mass reared at the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and University of Tennessee. The original genetic stock of S. tsugae has been phased out of the overall program with the initiation of field releases of the new genetic stock of S. tsugae. From 1995 - 1998, over 50 species of ladybeetles were collected from China, 21 of which were new to science. Three species of Scymnus, S. camptodromus, S. sinuanodulus, and S. ningshanensis, the most abundant ladybeetles feeding on HWA in China were investigated. Over 30,000 S. sinuanodulus beetles were released in eight states from 2005-2009, mostly in southern states where it is believed to be a better climate match. However, this predator provided no evidence of becoming established and was since abandoned. Likewise, two small experimental release of S. ningshanensis occurred in North Carolina, but was also abandoned because of rearing difficulties and lack of establishment. In the late 1990s, Laricobius nigrinus beetles were collected from British Columbia, and successfully established on HWA infested hemlock branches in quarantine facility at Virginia Tech. It was approved for release in 2000, and the first release was in 2003. Additional surveys and collections in Washington and Oregon resulted in the shipment of thousands of L. nigrinus (Seattle biotype). Over 250,000 have been released and are now becoming widely established in plant hardiness zones 6a and 6b. These establishments span 11 states from the southern Appalachians to New England and have become the first potential biological control agent of HWA to Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology P R O V I D I N G T E C H N O L O G Y F O R F O R E S T H E A LT H P R O T E C T I O N establish in such numbers that beetles can be fieldcollected and redistributed. Since 2007, L. nigrinus (Inland type) were collected from northern Idaho and northwest Montana, and released at a limited number of sites in New England. Small numbers of this biotype have since been recovered, indicating its adaptability to the more northerly climate and colder plant hardiness zones. A related species, Laricobius osakensis, was collected in Japan in 2005 and approved for release from quarantine in 2010. Extended studies in Japan determined that L. osakensis was the most abundant and frequently encountered predator of HWA in Japan, sharing many similarities to L. nigrinus in western North America. Study of the life histories of L. osakensis, HWA, and their interaction in Japan indicated a good synchrony between L. osakensis and HWA in the native habitat. L. osakensis has great potential as a biological control agent of HWA as the HWA found in the eastern U.S. originated from Japan. Because L. osakensis occurs in a broad range of climates in its native range, it should be well adapted to both southern and northern climates in the eastern U.S. L. osakensis was first released in 2012 and is currently being reared a VA Tech and University of TN. Since mid-2000, one survey in China and several surveys in the eastern U.S. were conducted for entomopathogens of HWA. One fungus, Lecanicillium muscarium (=Verticillium lecanii ) was recovered from HWA populations in the East and it has been investigated. Laboratory, ground, and aerial application trials to document its efficacy on HWA have been promising but the rapid degradation of the fungus once applied remains a challenge. The commercially available formulation of the fungus Mycotal® (Koppert Biological Systems, a Netherlandsbased company) along with MycoMax, a whey byproduct, has been added to the tank mix in an effort to stimulate fungal growth and spore production FO R MORE I NFORMATION CONTAC T: Richard Reardon Biological Control Program Manager USDA Forest Service 180 Canfield Street Morgantown, WV 26505 in the field. Meanwhile, registration of Mycotal® in the U.S. is being considered by Koppert pending completion of successful field trial demonstrations. Outlook High mortality of hemlocks in the eastern U.S. has been attributed to a combination of host tree susceptibility and lack of effective natural enemies of HWA. Significant effort has focused on classical biological control to increase the population of predators of HWA. In the northern part of the HWA range, the establishment of the predators, along with periodic HWA population reductions due to cold winter temperature may provide the additional mortality necessary to effectively suppress HWA populations below damaging levels. In the southern part of HWA range, due to lack of the cold temperature that reduce HWA populations exceptional high mortality from natural enemies may be needed to maintain HWA populations at innocuous level. Rearing and releasing of predators should be continued to promote their natural spread. The number of field insectaries should be expanded to allow increased harvesting and redistribution of the climate-adapted “wild” individuals. A biological control program integrated into management programs with early detection surveys, monitoring of pest density throughout the management effort, and a combination of control methods consistently applied through time will be necessary to obtain management objectives. A strategy of applying insecticide on a select number of large higher value hemlocks, and at the same time releasing and allowing the predators to become established on understory and non-treated trees is urgent for management of HWA in the southern U.S. This idea is that by protecting the health of and reducing HWA population density on the larger higher value hemlock trees, predators will have more time to populate sufficiently to offer long-term suppression of HWA populations. Phone: 304-285-1566 Fax: 304-285-1564 E-mail: rreardon@fs.fed.us