MODERNIZING STATE ENABLING LEGISLATION FOR LOCALLY DESIGNATED HISTORIC RESOURCES A THESIS

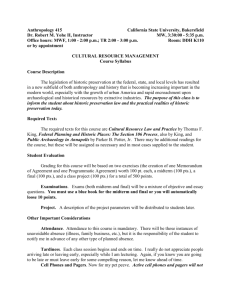

advertisement