REVITALIZE DOWNTOWN MUNCIE BY ATTRACTING STUDENTS AND ELDERS A CREATIVE PROJECT

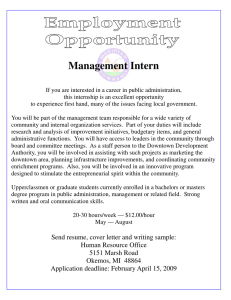

advertisement