Document 11001764

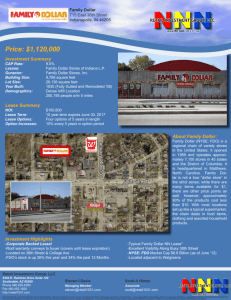

advertisement