A Contextual Analysis of Females Journey to the Superintendency in... A Dissertation Proposal Submitted to the Graduate School

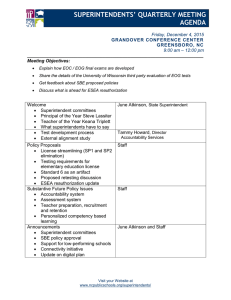

advertisement