Running head: INDIANA’S SCHOOL VOUCHERS 1

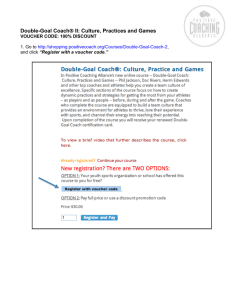

advertisement