Is Shared Leadership the New Way of Management? Comparison between... Shared Leadership Published By Science Journal Publication

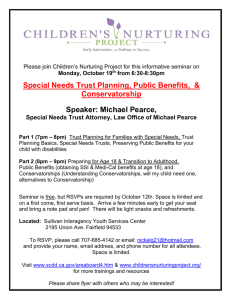

advertisement

Published By Science Journal Publication Science Journal of Business Management ISSN: 2276-6278 International Open Access Publisher http://www.sjpub.org/sjbm.html © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Research Article Volume 2012 (2012), Article ID sjbm-196, Issue 2, 5 Pages, doi: 10.7237/sjbm/196 Is Shared Leadership the New Way of Management? Comparison between Vertical and Shared Leadership Fragouli Evaggelia (Assistant Professor, Business School & Social Sciences, Aarhus University), Alexandra Vitta (Researcher) Corresponding Author Email: fragouli_evaggelia@yahoo.com Accepted 26 March, 2012 ABSTRACT-A lot of articles have been written in order to indicate the effectiveness of leadership in teams, in enterprises and organizations and especially the importance of shared leadership. The fascination with leadership seems an enduring human condition. Numerous theories of leadership have been espoused over the centuries. The primary emphasis of these theories has been the individual leader. The purpose of this research is to widen the debate on leadership to include, not only individual level leadership, but also to explore the possibilities of ‘shared leadership’ at the group level of analysis and thus suggest movement toward a multi-level theory of leadership. Finally, we compare shared leadership and vertical leadership and we analyse the evolution of leadership. Keywords: shared leadership ; vertical leadership ; management ; new venture Introduction Leadership is considered crucial for enabling team effectiveness and some researchers have even argued that it is the most critical ingredient. Yet most existing research on team leadership has focused narrowly on the influence of an individual team leader (usually a manager external to a team), thus largely neglecting leadership provided by team members (Carson et al. , 2007). Ensley et al. , 2006, defines shared leadership as a simultaneous, ongoing, mutual influence process within a team that is characterized by “serial emergence” of official as well as unofficial leaders. Although the need for shared leadership was explicitly described many decades ago, the concept has failed to gain traction within the mainstream leadership literature until recently. The knowledge underlying future paradigm shifts is often recognized by many individuals well before an actual paradigm shift occurs. The incentive structure must exist to motivate enough people to make the appropriate connections and actively build momentum toward moving beyond previous ways of thinking. It appears as though the current leadership paradigm is just now beginning to expand beyond the leader as commander outlook that has long dominated the field. This, we suggest, is a result of the proliferation of selfmanaged work groups , as well as the increased application of systems thinking, complexity theories and decentralized organizational designs. These events have forced individuals to rethink traditional views of leadership. This is not to say that vertical leadership is the way of the past, but rather that future thinking about leadership must encompass both vertical and shared facets in order to capture a fuller view of leadership processes and outcomes. Shared leadership Some historical points of developing shared leadership The top-heavy leadership myth has deep historical roots, but from a scientific point of view, it was during the Industrial Revolution that the task of organizational leadership began to be formally studied and documented. During the early 1800s, organizational leadership was formally recognized as an important component of economic activity when Jean Baptiste Say, a French economist, proclaimed that entrepreneurs must be capable of supervision and administration. Prior to this time, economists were primarily concerned with two factors of production – land and labor – and, to a lesser extent, capital. Accordingly, it was during the Industrial Revolution that the concept of leadership was recognized as an important ingredient of economic endeavors, and the predominant form of leadership was top-down command and control ( Pearce & Manz, 2005). Shared Leadership: An Alternative Social Source of Leadership The study of leader behavior has typically focused on the behavior of the appointed or elected leader of some group or organization . However, leadership can emerge from a context and be demonstrated by members (other than the designated leader) of the group or organization . Below we briefly review several historical lines of inquiry that are related to the concept of shared leadership. Table 1 presents a summary of the historical bases of shared leadership. The objective of this research is to unite these disparate historical underpinnings into an integrated conceptual framework for the understanding of shared leadership ( Pearce & Sims, 2000). Historical Bases of Shared Leadership Law of the Situation Perhaps one of the first writers to suggest that leadership can come from sources other than the designated leader was Mary Parker Follet. She wrote that the “law of the situation” suggests that one should let logic dictate to whom one should look for guidance based on individuals’ knowledge of the situation at hand. While she did not expressly write on the How to Cite this Article: Fragouli Evaggelia, Alexandra Vitta, “Is Shared Leadership the New Way of Management? Comparison between Vertical and Shared Leadership ,” Science Journal of Business Management, Volume 2012 (2012), Article ID sjbm-196, Issue 2, 5 Pages, doi: 10.7237/sjbm/196 Science Journal of Psychology (ISSN: 2276-6278) idea of shared leadership, per se, her “law of the situation” is a clearly related concept in that the situation, not the individual, provides the basis for leadership ( Pearce & Sims, 2000). Page 2 viewed as a special case of the more traditional vertical leadership. Thus, while co-leadership is clearly related to shared leadership, it is distinct ( Pearce & Sims, 2000). Followership Emergent Leadership More recent authors have explored the concept of emergent leadership. Emergent leadership primarily refers to the phenomenon of leader selection from a leaderless group . Emergent leadership is similar to what, in this research chapter, is termed shared leadership. However, the concepts are distinct. While emergent leadership is typically concerned with the ultimate selection of an ‘appointed’ leader, the concept of shared leadership is concerned with an alternate source of leadership for ongoing team functioning ( Pearce & Sims, 2000). Substitutes for Leadership The ‘substitutes for leadership’ literature also provides a possible framework for understanding the concept of shared leadership. The substitutes for leadership literature suggests that certain conditions, such as highly routinized work or professional standards, may serve as substitutes for social leadership. Whether or not these substitutes are actually substitutes or are systematized outcomes from previous leadership practices is debatable. However, whether or not there are substitutes for leadership is not of concern when classifying shared leadership. Shared leadership is not a substitute for social leadership it is social leadership, albeit from a different social source than that traditionally studied in the leadership literature. However, as used in this research, it may be that shared leadership can serve as a substitute for more formal appointed leadership. Manz and Sims brought forth this point, at the individual level, in their article, ‘SelfManagement as a Substitute for Leadership ( Pearce & Sims, 2000). Vertical Dyad Linkage Theory Other recent authors have explored the role of subordinates in the leadership process. For example, Graen and colleagues , have discussed the importance of the leader-follower dyad in their work on leadership process. Their work suggests that followers have a role in the leadership process but do not go as far as to say that the source of leadership can be from the followers, as is the case with shared leadership ( Pearce & Sims, 2000) . Co-leadership Co-leadership research focuses on situations in which two individuals simultaneously engage in one leadership position. Co-leadership research is predominated by research in group therapy where co-leaders occupy mentorprotégé relationships. Much of this research examines how coleadership develops and tactics for improving co-leadership effectiveness . In some ways co-leadership can be considered a special case of shared leadership – the two person case. However, since co-leadership research is primarily concerned with mentor-protégé relationships, in other ways it might be While followers have not been of central interest in leadership research, several scholars and practitioners from widely disparate fields have emphasized the role that followers play in the leadership process. The primary emphasis of this line of research is the definition of ‘good’ followership. Kelly defined good followers as those who have the vision to see both the forest and the trees, the social capacity to work well with others, the strength of character to flourish without heroic status, the moral and psychological balance to pursue personal and corporate goals at no cost to either, and, above all, the desire to participate in a team effort for the accomplishment of some greater purpose. Thus, while the followership literature illuminates the indispensable role followers play in the leadership equation it does not illuminate the role of ‘followers’ in sharing the leadership process ( Pearce & Sims, 2000). Empowerment and Self-leadership The topic of empowerment and self-leadership has received considerable attention in recent years . The central issue in the empowerment literature is that of power . Whereas traditional models of management emphasize power emanating from the top of an organization, empowerment emphasizes the decentralization of power. The rationale behind the empowering of individual workers is that those dealing with situations on a daily basis are the most qualified to make decisions regarding those situations. While the vast majority of the empowerment literature focuses on the impact on the individual some researchers have expanded the concept to the group level of analysis. However to empower, or share power, with members of a group is not the same as observing shared leadership emanating from a group. Shared leadership only exists to the extent that the group actively engages in the leadership process ( Pearce & Sims, 2000). Self-managing Work Teams Recent work on self-managing work teams (SMWTs) has taken the boldest steps toward the concept of shared leadership . However, while recognizing that team members can, and do, take on roles that were previously reserved for management, this literature primarily focuses on the role of the vertical leader and less on the role of the team as a whole in the leadership process . Thus, while the self managing work teams literature does acknowledge the role of team members in the leadership process, it does not go so far as to suggest a systematic approach to the examination of how, and to what effect, the process of leadership can be shared by the team as a whole ( Pearce & Sims, 2000). Generally The entrepreneurship literature has long been preoccupied by the concept of the lone entrepreneur who against all odds – creates a new venture and single handedly takes down larger, more established incumbents. This fascination with Page 3 Science Journal of Psychology (ISSN: 2276-6278) the individual entrepreneur as the nexus of the venture creation process has led entrepreneurship researchers on an unproductive quest to identify the optimal traits of individual entrepreneurs and has placed an overemphasis on vertical leadership within the new ventures context, while relatively neglecting founding teams as an area of research. This is unfortunate considering that relying solely on vertical leadership in top management teams would seem “to ignore leadership dynamics within a group context (Ensley et al. , 2006). their team, they should experience higher commitment, bring greater personal and organizational resources to bear on complex tasks, and share more information. When they are also open to influence from fellow team members, the team can function with respect and trust and develop shared leadership that in turn becomes an additional resource for improving team process and performance. This intangible resource, which is derived from the network relationships within the team, results in greater effort, coordination, and efficiency. Shared leadership occurs when all members of a team are fully engaged in the leadership of the team: Shared leadership entails a simultaneous, ongoing, mutual influence process within a team, that involves the serial emergence of official as well as unofficial leaders. In other words, shared leadership could be considered a case of fully developed empowerment in teams. Several studies have documented the importance of shared leadership across a wide variety of contexts— including top management teams, change management teams, teams of volunteers, research and development teams, virtual teams, and even military squads. In fact, several studies indicate that shared leadership is an even better predictor of team success than just leadership from above. Thus, the initial evidence points to an increasingly important role for shared leadership, particularly in the knowledge worker context. As one striking example,consider the case of the Braille Institute of America (Pearce & Manz, 2005). Only a handful of empirical studies have been conducted with shared leadership as an explicit source of leadership, but the results are promising. Some colleagues explored shared leadership among teams of undergraduate students and found a positive correlation with self-reported effectiveness. Pearce and Sims studied the relationship between shared leadership and change management team effectiveness at a large automotive manufacturing firm and found shared leadership to be a more useful predictor than the vertical leadership of appointed team leaders. Some other colleagues found that team leadership, defined in a manner similar to previous definitions of shared leadership as the collective influence of team members on each other, was positively related to both team performance and potency over time in a sample of undergraduate business students. It has been studied that shared leadership in virtual teams engaged in social work projects and again found that shared leadership was a stronger predictor of team performance than vertical leadership. Also it has been found that shared leadership to be a stronger predictor than vertical leadership of new venture performance in a sample of top management teams. Finally, there is also indirect support for shared leadership predicting team performance. The models of leadership The transactional–transformational model While the dominant model used in leadership development today is the transactional–transformational model, the subject of much academic leadership research a revisionist movement has begun to question whether scholars are missing the potential of a broader range of leadership options by coalescing too narrowly on this two-factor model. Pearce, 2007 identified this concern by observing that the transactional– transformational model “is fast becoming a two-factor theory of leadership processes, which is an unwarranted oversimplification of a complex phenomenon. The alternative models offered in this special issue The vast majority of the articles in this special issue—five of the seven—specify models that identify behaviors or competencies for the focus of leadership development efforts. One article provides a conceptual view on leadership development and the last documents a process model—a veritable “how to” manual—for leadership development in the context of “onboarding” leaders into an organization (Pearce, 2007). Shared Leadership and Team Performance Shared leadership is an important intangible resource available to teams, and therefore it should enhance team performance on complex tasks. When team members offer their leadership to others and to the mission or purpose of It has been examined that emergent leadership within teams and found that team performance was greatest when other team members, in addition to the emergent leader, demonstrated high levels of leadership influence. Failure of even a single member to exhibit leadership behavior was found to be detrimental to team performance. Although shared leadership was not formally defined or measured, these findings seem to support the notion that shared leadership may result in greater effectiveness than the emergence of a single internal team leader. Taken as a whole, these studies suggest that shared leadership is an important predictor of team performance and provides a resource for teams that goes beyond the leadership of any single individual ( Carson et al. , 2007). Benefits of Shared Leadership In many ways the research on shared leadership is still in its infancy, but noteworthy benefits and limitations have emerged from the few studies that have been undertaken. Perhaps the most commonly cited benefit concerns the synergy and expertise derived from a shared leadership model. Here, the old adage two heads are better than one seems appropriate. Leaders can utilize their individual strengths, and organizations can benefit from diversity of thought in decision making. Bligh posited that influence is fluid and reciprocal, and team members take on the leadership Science Journal of Psychology (ISSN: 2276-6278) tasks for which they are best suited or are most motivated to accomplish. O’Toole noted that two or more leaders are better than one when the challenges a corporation faces are so complex that they require a set of skills too broad to be possessed by any one individual. Indeed, Many have argued that during times of change and reorientation in a hotel corporation, shared leadership between two leaders, one task-oriented and the other behavior-oriented, would result in greater success than leadership by one person alone. Reduced stress levels for key leaders also make this model attractive, as a more robust, shared leadership system does not unduly burden any single leader. Furthermore, some other authors extolled the virtue of shared leadership as it exploits the wealth of talent present in an organization, capturing energy and enthusiasm, thereby creating a distinct competitive advantage. Flow and creativity seem to flourish in a shared leadership environment. Moreover, teams often work better when leadership is shared. In a study involving road maintenance teams, Hiller found collective leadership to be positively associated with team effectiveness. Finally, Ensley suggested that “Shared leadership appears to be particularly important in the development and growth of new ventures” ( Kocolowski, 2010). Empowering leadership and shared leadership Empowering leadership from the CEO ( Chief Executive Officer) is a critical element in creating shared leadership in the top management team . Empowering leadership behaviors encourage the development of followers who can make independent decisions, think and act autonomously without direct supervision, and generally take responsibility for their own work behaviors . Moreover, the empowering leadership process strives to create followers who are capable of teamwork and effective shared leadership . Empowering leadership entails modeling effective selfleadership behaviors and advocating the use of shared leadership within the team. Empowering leadership focuses on viewing mistakes as learning opportunities , as well as having a primary emphasis on listening and asking questions rather than talking and providing answers. An empowering leader strives to replace conformity and dependence among followers with initiative, creativity, independence, and interdependence. The critical element to our model here is the notion that shared leadership is created and developed by empowering leadership from above. Several empirical studies by Pearce and colleagues have identified a positive relationship between empowering leadership from above and the development of shared leadership in teams, including top management teams (Pearce et al. , 2008 ) . Shared leadership and corruption The empirical evidence on shared leadership, to date, has consistently linked it with positive organizational outcomes. Most of the studies have examined some dimension of performance, however, several have examined other constructs, such as team dynamics. Most related to our purpose, it has been found that shared leadership is an effective mitigation against the emergence of anti citizenship behaviour in teams. Pearce defined anti citizenship behaviour Page 4 as including defiance and avoidance of work, and is also similar to the concept called counterproductive work behaviour. Further, there was found a link between citizenship and ethical behaviour (Baker, Hunt, & Andrews 2006). While anti citizenship behaviour may not rise to the level of Enron-like corruption, it clearly serves as a preliminary indicator that supports our analysis here: Once certain forms of corrupt behaviour are tolerated a slippery slope is encountered where other more egregious forms become tolerated and the cycle continues . As such, and in line with, shared leadership appears to provide a buffer against corruptive influences. More specifically we view shared leadership as an important moderator of the relationship between predisposition of the CEO for corruption (as measured by responsibility disposition) and engagement in corruption at the executive level of the organization. The crux of our argument is that shared leadership can provide a robust system of leadership checks and balances, thereby acting as a moderator of the relationship between CEO responsibility predisposition and executive corruption. ( Pearce et al, 2008) Distinguishing between vertical and shared leadership Leadership is the process of influencing others to understand and agree about what needs to be done and how it can be done effectively, and the process of facilitating individual and collective efforts to accomplish a shared objective. In top management teams, there are two potential sources of leadership, which are defined by “who” engages in leadership. The first source, the vertical leader, has received considerable attention and support in the literature (Gerstner & Day, 1997). The second source, the team, has been the focus of an emerging stream of research that views the team as a potential source of leadership. Vertical leadership may be viewed as an influence on team processes. In contrast, shared leadership is a team process where leadership is carried out by the team as a whole, rather than solely by a single designated individual. To this end, vertical leadership is dependent upon the wisdom of an individual leader, whereas shared leadership draws from the knowledge of a collective. Further, vertical leadership takes place through a top–down influence process, whereas shared leadership flows through a collaborative process. Here we focus on four fundamental types of leadership that team members might share—directive, transactional, transformational, and empowering (Pearce, 2004). Shared directive leadership, for example, might be expressed as peers test one another with a directive give-and-take about how to engage key stakeholders, develop strategic initiatives or how to create internal systems and structures. Similarly, shared transactional leadership might be expressed through collegial recognition of efforts and contributions or by establishing key performance metrics and distributing rewards based on those metrics. Additionally, teams might engage in shared transformational leadership through the creation of a shared strategic vision or by inspiring one another to challenge existing industry standards and norms to create breakthrough products or services. Finally, shared empowering leadership might be expressed in a team through peer-based support and encouragement of providing self-rewards, viewing personal obstacles as opportunities to learn or engaging in teamwork How to Cite this Article: Fragouli Evaggelia, Alexandra Vitta, “Is Shared Leadership the New Way of Management? Comparison between Vertical and Shared Leadership ,” Science Journal of Business Management, Volume 2012 (2012), Article ID sjbm-196, Issue 2, 5 Pages, doi: 10.7237/sjbm/196 Page 5 Science Journal of Psychology (ISSN: 2276-6278) and participative goal setting with other members of the team. The following sections elaborate on the importance of both vertical and shared leadership within the new venture context (Ensley et al. , 2006). Conclusion It has become increasingly clear in recent years that the conceptualization of leadership must be broadened beyond that of top–down heroic leadership. As has been demonstrated in the current article, shared leadership processes add substantial insight into the performance of organizations. Further, shared leadership appears to be particularly important in the development and growth of new ventures. Within this context, the explanatory value of shared leadership goes above and beyond that of vertical leadership. This suggests that high profile cases of prodigal entrepreneurs, whose individual creativity and charisma have led them to fame and fortune, are more myth than reality. If nothing else, the leadership of the principal founder is only part of the story behind most successful start ups. It takes the leadership of an array of talented individuals to develop and grow new ventures. This highlights the great importance in selecting and developing top management teams, rather than simply attracting a superstar CEO: It is time to move beyond the moribund myth of the heroic entrepreneur as the sole leader of the firm. References 1. Baker, L., Hunt, G. & Andrews, C. (2006). Promoting ethical behavior and organizational citizenship behaviors: The influence of corporate ethical values. Journal of Business Research, 59(7): 849−857. 2. Carson , J. , Tesluk , P., Marrone , J. ( 2007 ) Shared leadership in teams: an investigation of antecedent conditions and performance, Academy of Management Journal 50 ( 5 ) : 1217–1234. 3. Ensley , M. , Hmieleski, K., Pearce, C. ( 2006 ) The importance of vertical and shared leadership within new venture top management teams: Implications for the performance of startups , The Leadership Quarterly 17 : 217–231 . 4. Gerstner, C., & Day, D. (1997). Meta-analytic review of leader–member exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6) : 827–844. 5. Kocolowski, M. ( 2010 ) Shared leadership : Is it time for a change? Emerging leadership journeys. 6. Pearce , C. ( 2007 ) The future of leadership development: The importance of identity, multi-level approaches, self-leadership, physical fitness, shared leadership, networking, creativity, emotions, spirituality and on-boarding processes, Human Resource Management Review 17 : 355–359. 7. Pearce , C. , Manz , C. ( 2005 ) The New Silver Bullets of Leadership: The Importance of Self- and Shared Leadership in Knowledge Work , Organizational Dynamics, 34(2) :130–140. 8. Pearce , C. , Manz , C. , Sims, H. ( 2008 ) The roles of vertical and shared leadership in the enactment of executive corruption: Implications for research and practice. The Leadership Quarterly 19 : 353–359. 9. Pearce, C. (2004). The future of leadership: Combining vertical and shared leadership to transform knowledge work, Academy of Management Executive, 18(1) : 47–57. 10. Pearce , C., Sims, H. (2000) Shared leadership: toward a multi- level theory of leadership Team Development, 7 :115–139. How to Cite this Article: Fragouli Evaggelia, Alexandra Vitta, “Is Shared Leadership the New Way of Management? Comparison between Vertical and Shared Leadership ,” Science Journal of Business Management, Volume 2012 (2012), Article ID sjbm-196, Issue 2, 5 Pages, doi: 10.7237/sjbm/196