The Revival of Reliabilism: A Mathematical Approach to the Generality Problem

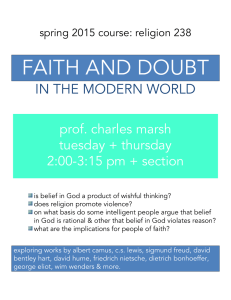

advertisement

Volume 1 (2013) The Revival of Reliabilism: A Mathematical Approach to the Generality Problem Justin Svegliato Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, Marist College Abstract In this paper, reliabilism, a theory of epistemic justification most clearly articulated by Alvin Goldman, is amended in order to avert the threat of the generality problem. More particularly, I argue that the reliability of belief-forming processes can no longer merely be in terms of the success rate; rather, it must be a function of both the success rate and the corresponding number of instantiations. Thereafter, I introduce a method to objectively specify belief-forming processes in terms of all relevant considerations that affect reliability. Finally, potential simplifications to the proposed theory are discussed as well. I. Introduction In “Reliabilism: What is Justified Belief?,” Alvin Goldman offers an externalist account of epistemic justification where a belief is justified if and only if it is formed via a reliable process.1 Despite its initial attractiveness, the generality problem—namely that that the reliability of a given process is contingent upon the broadness of its specification—undermines the initial tenability of reliabilism insofar as one can no longer assign an objective degree of reliability to belief-forming processes. In this paper, I will proceed by explaining (1) the fundamental features of the current formulation of reliabilism and (2) the threat of the generality problem. Thereafter, I will (3) argue for an altered account of reliabilism that effectively handles the generality problem by defining the reliability of a process in terms of its success rate and corresponding number of instantiations, (4) demonstrate the revised account ascribing an accurate level of reliability to 1 Alvin Goldman, "Reliabilism: What Is Justified True Belief?," in Arguing about Knowledge, ed. Ram Neta et al. (New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2009), 157-73. 18 Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) singularly instantiated processes, (5) provide a methodology for objectively describing beliefforming mechanisms to circumvent the reliance of the success rate, a component of reliability, upon an arbitrary degree of generality, and finally (6) offer a reductive account of process specifications to reduce the infinite set of all potential belief-forming mechanisms to a finite subset. II. An Explanation of Reliabilism Before outlining reliabilism, it is important to understand the concept of a belief-forming process since the justificational status of a belief depends upon the reliability of a process according to the theory. In a word, a belief-forming process is “a functional operation or procedure, i.e. something that generates a mapping from certain states—“inputs”—into other states—“outputs.” The outputs in the present case are states of believing this or that at a given moment.”2 That is to say, it is a process, particularly perception, reasoning, or perhaps recollection, that yields a belief.3 For instance, consider Ryan, an agent of average intellectual capacity not suffering from any physical limitations, who notices a tree outside while sitting at his desk. He consequently forms a belief that a tree is outside on the basis of what he sees. In this case, the belief-forming process is visual perception to the extent that it is the functional operation that generates his belief. Now consider Ryan attempting to solve a simple arithmetic problem, perhaps the addition of five and six. The belief-forming process is the method by which he arrives at an answer to the problem; in particular, his use of reasoning is the operation that generates his proposed solution. 2 Alvin Goldman, "Reliabilism: What Is Justified True Belief?,” 164. The distinction between types and tokens is important in understanding the discourse that will follow. “Types are generally said to be abstract and unique; whereas tokens are concrete particulars, composed of ink, pixels of light (or the suitably circumscribed lack thereof) on a computer screen, electronic strings of dots and dashes, smoke signals, hand signals, sound waves, etc.” Linda Wetzel, “Types and Tokens,” Stanford Encylopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2006 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL= http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/types-tokens/. For instance, a specific type is the abstract category of a bicycle. However, the road bicycle that Lance Armstrong rides or perhaps the mountain bicycle that I ride on the weekend are both examples or more accurately tokens of the given type bicycle. In discourse regarding belief-forming processes, there is a difference between types and tokens. A type may be considered visual perception whereas tokens of this type would be specific instances of when a belief is formed via visual perception. More specifically, in the scope of this paper, a process is considered an abstract category, i.e., a type, whereas the instantiations of this process are considered tokens. 3 19 Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) More importantly, however, Ryan may or may not arrive at the correct answer to the problem. He may wrongly conclude that the sum of five and six is fifty-six. Despite arriving at an incorrect answer, his reasoning generates a belief and is still a belief-forming process. Thus a belief-forming process is independent of whether the generated belief is true—the mere production of beliefs is sufficient for a process to be belief-forming. In fact, one may utilize a process that never produces true beliefs in some cases. Nevertheless, this process is still classified as belief-forming in virtue of its ability to generate beliefs—without respect to their truth or falsity—given certain inputs. Insofar as these processes may yield false beliefs, Goldman claims that a level of reliability, a quantity contingent upon the likelihood that a generated belief will be true rather than false, can be assigned to a belief-forming process. He then offers an account of epistemic justification where one’s doxastic attitude—namely, an attitude that pertains to beliefs and perhaps others mental states such as desires, judgments, thoughts, and opinions—is justified if and only if the process that led to the doxastic attitude is reliable, “where (as a first approximation) reliability consists in the tendency of a process to produce beliefs that are true rather than false.”4 That is, a belief-forming process must have a high success rate, namely the likelihood of yielding a true belief must be sufficiently high, for the agent’s doxastic attitude, specifically his or her belief, to be justified. Hence, reliability is solely a function of the success rate, particularly the number of tokens that result in true beliefs divided by the total number of tokens generated by the given belief-forming process. For instance, suppose Ryan is looking at a tree in a meadow during a clear day. According to reliabilism, he is justified in believing it is a tree provided that visual perception under the conditions specified—the weather and location, two variables that significantly affect sight in part due to the degree of illumination and the distance to the observed object, as well as various other factors—is generally reliable. In particular, the success rate of the process that 4 Alvin Goldman, "Reliabilism: What Is Justified True Belief?," 163. 20 Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) yielded his belief is sufficiently high due to these circumstances, and thus his belief is justified according to the reliabilist account of epistemic justification. Conversely, suppose that Ryan’s belief is the result of an unreliable process. Perhaps the conditions under which the sighting occurs are poor due to factors, such as fog and bad lighting, that hinder his visual perception. As a result, these circumstances lower the success rate and thereby lower the reliability of the beliefforming process to such an extent that any belief generated by the said process, including the belief held by Ryan, will be unjustified. In these sorts of prototypical cases, reliabilism captures the way we think about the attribution of justification to beliefs; the markedly simple and intuitive manner in which this attribution occurs is an attractive feature that demonstrates the efficacy of the theory. III. The Threat of the Generality Problem Although reliabilism seems to accurately attribute justification to doxastic attitudes, the generality problem challenges the precision of these ascriptions. In a word, the reliability of a given belief-forming process is wrongly contingent upon the broadness or narrowness of its specification. According to Goldman, “input-output relations can be specified very broadly or very narrowly, and the degree of generality will partly determine the degree of reliability” 5. That is to say, the justificational status of beliefs will fluctuate with the level of generality used to specify that process.6 Recall the example of Ryan forming the belief that a tree is outside his window. The process in this case may be expressed as “looking at a tree while sitting at a desk.” However, the process may also be described as visual perception or perhaps more broadly as mere perception. Conversely, the process specification may be narrower, namely “looking at a tree while sitting at a desk during a cloudy day.” Or the process could be described as “looking at a tree in a field while sitting at a desk during a cloudy summer day in Australia as night is just about to fall.” The 5 Alvin Goldman, "Reliabilism: What Is Justified True Belief?," 165. Similar concerns have been raised in John Pollock, “Reliability and Justified Belief,” Canadian Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 14, No. 1(1984): 103-114. Also see Earl Conee and Richard Feldman, “The Generality Problem for Reliabilism,” Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition, Vol. 89, No. 1 (1998): 1-29. 6 21 Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) description of the process whereby he forms his belief could become considerably if not perhaps infinitely more specific. Thus, there are countless specifications, all of which are equally viable according to reliabilism, that could sufficiently describe and encompass all tokens of the given belief-forming process that Ryan employs. This is to say that the validity of all specifications for a given process rests not upon the degree of generality but rather upon their ability to encompass all tokens under consideration. So long as the description covers all tokens in question, the generality of a given specification has no bearing upon its correctness. Such a consideration has an impact upon the feasibility of reliabilism. For instance, in the original specification of the process, namely “looking at a tree while sitting at a desk,” the reliability is maximal, and thus the agent is justified in forming his belief in virtue of the conditions of the process. However, when the specification is broader, i.e. visual perception and perception, the reliability, whatever it may be, may not be of the same reliability as the original specification. Similarly, in the more specific descriptions of the process, say, “looking at a tree while sitting at a desk during a cloudy day,” the reliability decreases provided that the augmentation adds a condition that undermines perception. With this narrower specification, Ryan is most likely still justified in his belief that he is looking at a tree; however, the reliability of the belief-forming process changes. Therefore, in certain scenarios the justificational status of a belief may vary if the reliability deviates too greatly between two satisfactory albeit distinct specifications of the process. Thus, which of the specifications of the belief-forming process in the example of Ryan is correct? Which should determine whether his doxastic attitude is justified? Without an answer to these questions, the theory cannot determine the justificational status of a belief since the reliability of processes supervenes upon an arbitrarily chosen degree of generality of their process specifications. That is, the justificational status of a doxastic attitude can change by manipulating how the process that yielded that belief is specified. Consequently, reliabilism appears to be an untenable theory because it fails to ascribe an objective justificational status to a doxastic attitude given its inability to offer a sole level of reliability. 22 Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) It is important to consider one last consequence of the generality problem. When a beliefforming process is narrowly specified, there is only one token upon which the reliability of that process, a function in terms of the success rate, is contingent. That is to say, the reliability will rest upon a single instantiation of the process given a narrow specification. For instance, suppose an agent who is nearly blind, Sally, notices a “Route 912” sign on a foggy winter night while driving her car at 130 miles per hour on an expressway. Naturally, most would agree that this process is unreliable. Suppose, however, she fortuitously forms a belief that the sign reads “Route 912.” As a result of this detailed specification, Sally’s belief formation in this rare scenario is the only instantiation—i.e., the only token—of the process in question. Hence, this intuitively unreliable process is reliable on the standard account of reliabilism because the only instantiation of the process generated a true belief. Therefore, given the function of reliability offered by the standard account—namely a quantity only in terms of the success rate that is further reducible to the number of instantiations that yield true beliefs divided by the total number of instantiations—the reliability of the process will be maximal. This conclusion necessitates that her doxastic attitude is fully justified, a result that is inconsistent with the way we intuitively think about justification. IV. The Mathematical Definition of Reliability Resolution of the singularly-instantiated process aspect of the generality problem demands that the reliability of a belief-forming process cannot only be in terms of the success rate. In particular, reliability cannot merely rest upon the tendency of a given process to produce true rather than false beliefs, as this quantity is partly determined by the degree of generality of the specification. Hence we must modify the traditional definition of reliabilism to consider another quantity in addition to the success rate. However, discovering this other quantity involves analyzing the process by which reliabilism determines the justificational status of a belief generated by a singularly-instantiated process, particularly the scenario of Sally forming her belief that the sign reads “Route 912.” 23 Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) In this case, we established that the reliability of the belief-forming process in question is maximal, and thus her belief is justified despite that such a conclusion is inconsistent given the undesirable conditions of the process. Her forming the belief that the sign reads “Route 912” should—at least to some extent—contribute to the level of reliability; yet, it should not confirm nor deny that the reliability of the process is maximal merely in virtue of a single instantiation. In other words, we are not confident in whether this mere instantiation is an accurate representation of the process in totality, and it is therefore conceivable that the likelihood that the success rate is accurate increases with number of instantiations. In essence, if there are many instantiations for a given process, we are more confident that the success rate correctly portrays every instantiation whereas singularly instantiated mechanisms intuitively lack this sort of empirical support. Hence the reliability of a singularly instantiated process should be rather low to the extent that the token may have generated a true belief on the basis of luck. Consider, however, a multiply instantiated process of, say, eighty instantiations, and suppose that that the success rate is roughly eighty-five percent. Insofar as we are confident that the success rate is accurate given a sufficient number of instantiations, the reliability of the belief-forming process will approximately equal the success rate. Thus the high number of instances of the process ensures that luck is not the factor generating true beliefs; rather, this process is reliable as the result of some truth-conducive characteristics or abilities. In virtue of the tendency of the mechanism to generate true rather than false beliefs on the basis of some property or disposition, we are more confident that the process is reliable for good reasons. Necessarily, the likelihood that the success rate is accurate relies upon the total number of tokens because a high quantity of instantiations suggests that there exists some truth-conducive disposition possessed by the mechanism. Therefore, to confirm that the reliability of a process is accurate and not the result of fortuity, reliability must be a function of the success rate as well as the total number of instantiations of the process requiring that the reliability of a given belief-forming mechanism is defined by the function 24 Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) ( where s is the success rate and ) 7 is the total number of instantiations. However, the success rate may be further reduced to the equation , where is the number of instantiations that yield true beliefs. So the reliability of a process may be more simply expressed as the function ( ) 8 It is important to note that the function will never generate a reliability exceeding the success rate. That is to say, the reliability will get infinitely close to but never equal the success rate as the number of instantiations increases. In other words, the asymptote of the function is always the specified success rate. This result is intuitive since the reliability of a process is partly the measure of how confident we are in believing that the success rate is accurate. For instance, if a high number of instantiations of a particular process generate true beliefs then it is likely that the success rate of that process is accurately represented; namely, the success rate is roughly equivalent to the reliability. Following a similar line of reasoning, the reliability will be significantly lower than the success rate given a low number of instantiations. Therefore, the reliability of the particular process logarithmically increases with respect to the total number of instantiations until the process reliability equals the asymptotic success rate. 7 See the appendix for the derivations of all equations used throughout the paper. Throughout the paper, I correctly state that reliability is a function of both the number of instantiations and the success rate of the process. However, in order to simplify the number of variables used in the reliability formula, I restate the success rate in terms of its constituent parts—namely the number of tokens that generate true beliefs and the total number of tokens—and then substitute that proportion in for every occurrence of the success rate in the first statement of the reliability formula. I initially express reliability in terms of the success rate and the total number of instantiations for pedagogical concerns; however, it is important to understand that reliability can be viewed as a function of both the success rate and the total number of tokens as well as a function of the total number of tokens and the number of tokens that generate true beliefs. 8 25 Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) V. The Correct Specificity of Belief-Forming Processes While the reliability of belief-forming processes is now in terms of both the success rate and the total number of instantiations, the generality problem still challenges the validity of the theory because the degree of generality of a process specification partly determines the degree of reliability. For example, recall the example of Ryan looking at a tree in a field. We determined earlier in the paper that the success rate of a belief-forming process is partly contingent upon an arbitrary degree of generality thereby resulting in a subjective ascription of reliability. Therefore, the revised account of reliabilism—despite its success in assigning accurate reliabilities to singularly instantiated processes—cannot yet handle an important consequence of the generality problem, namely its inability to assign an objective level of reliability to belief-forming mechanisms. There is, however, a clear resolution to this problem as a result of revising the calculation of reliability. When the reliability of a process was merely a function of the success rate, processes were specified broadly to prevent reliability from resting upon a single instantiation. Fortunately, however, a broad specification of belief-forming processes is no longer indispensable to the theory given the increased accuracy of reliability ascriptions to infrequently instantiated processes, that is, mechanisms that have but a few tokens. Instead the modified theory conversely necessitates narrow process specifications to account for all conditions upon which the efficacy of a particular process depends; viz., a specification must contain only those details affecting the reliability of a process. Any superfluous factors that have no bearing upon the reliability of a process ought not to be contained within its specification. As a result, a process is sufficiently described if and only if all relevant factors—particularly, those that affect the success rate of the process—are included in the specification. For instance, consider the case of Ryan noticing a tree in a field. Various details, such as the color of his shirt or jeans, are not relevant considerations with respect to the reliability of the process and therefore ought not to be contained in the specification. On the other hand, details, such as the location, weather, or perhaps physical or mental defects of the observer, are necessary constituents of the specification since each affects his capacity for visual perception. 26 Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) It is again important to note that specifications may be unavoidably narrow necessitating that there may exist only one instantiation for certain processes; however, the modified account of reliabilism that I have proposed can adequately handle these situations. On the contrary, if the process specification does not contain all relevant details affecting the instantiation’s efficacy, the reliability of that process will not be accurate to the extent that a token that ought to be categorized under one specification may be perhaps categorized under another specification. For instance, consider two situations where the descriptions of the processes are sufficient. First, suppose that James is eavesdropping on a conversation in a crowded mall. Further, suppose that Ryan, shopping at the mall as well, is eavesdropping on the same conversation while also wearing hearing aids. They both then form beliefs about the topic of the conversation and are both one of many instantiations of each corresponding process specification. However, suppose that the specification of the process of the latter case was insufficient: it did not include that Ryan is wearing hearing aids. As a result, the situation of Ryan, an instantiation of a process, would be inappropriately grouped with an instantiation of a much different process. Thus a token that should have been categorized under one process is now inaccurately identified under another process. Hence the reliability of each process will not represent the entire set of instantiations that belong under each corresponding specification. By incorporating all relevant factors that affect reliability, we are enforcing an objective level of generality, and so the reliability of process will not be contingent upon an arbitrary degree of generality. VI. The Simplification of Process-Type Specifications Assume the process specification of some set of tokens, say looking at a tree in a field while wearing glasses, is sufficient and is expressed in terms of all factors affecting reliability. Conceivably, our current specification of processes is colloquial and informal, for the expression of relevant considerations relies upon everyday adjectives and language. This further complicates the calculation of reliability, as the informality of process specifications causes many to falsely claim that two identical processes are distinct. For instance, again recall the case of Ryan noticing a tree while sitting at his desk and furthermore consider a scenario whereby Molly is 27 Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) looking at a tree through a window. In both scenarios, both Ryan and Molly are using visual perception but the relevant considerations or factors, namely the location of the agent in question, are distinct according to language and thus both examples represent two disjoint processes. However, are these processes truly distinct? Are the mere locational details of each instantiation enough to identify the two tokens as two distinct processes? It is rational to consider the case of Ryan and Molly as instantiations of two distinct processes insofar as the difference in location affects reliability. The location, however, is only a relevant consideration in virtue of its affect on the efficacy of the sight of Ryan and Molly. What if the locations of each agent affected visual perception in an identical way? That is, we can perceive the location of visual perception as important only with respect to its affect on the degree of illumination in the proximity of the observer and the observed. Therefore, the processes of Ryan and Molly—rather than being in terms of mere location—may be expressed in terms of the degree of illumination at that particular location. For example, the process in Molly’s scenario can be better described as “observing a tree with a degree of illumination x” whereas the process-type in Ryan’s situation can be expressed as “observing a tree with a degree of illumination y.” In these cases, each process is not specified in terms of the location; rather, it is in terms of a more simplistic and informative descriptor, namely the degree of illumination. Hence, if the degree of illumination is identical—i.e. x is equal to y in reference to the cases of Ryan and Molly—in both locations, then the processes are surprisingly identical and there would be no significant distinction between the two instantiations despite a difference in environment. Thus our original conception of process specifications must change. Particularly, instead of representing instantiations with informal descriptions consisting of commonplace modifiers concerning environmental factors, the specification must contain only those attributes, which are derivations of more colloquial language, directly affecting the mechanisms in question. This reductive formulation yields a simplified set of processes insofar as many previously distinct mechanisms are now considered equivalent thereby transforming the once infinite set of 28 Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) processes into a more fundamental subset.9 In a word, eliminating unnecessarily specific environmental details and instead incorporating the conditions affecting reliability, such as the degree of illumination, will reduce many previously distinct processes into one mechanism. Using this sort of reasoning, other nontrivial details, such as the time, weather, and even psychological and physical deficiencies of the process instantiator, are reducible to more fundamental factors affecting the process. As a result, process specifications must always be expressed in terms of the most fundamental qualities to yield a simplified finite set of mechanisms. VII. The Categorization of Belief-Forming Processes At present, I have offered a modified account of reliability that handles all facets of the generality problem; that is, the theory now yields objective specifications for processes since reliability no longer relies upon an arbitrary degree of generality while also assigning accurate reliabilities to singularly instantiated processes. However, in order to provide a more practical account of reliabilism, I will describe a method by which the total reliability of primary processes, particularly the most general mechanisms that generate beliefs, can be calculated. All mechanisms can be essentially interpreted as either a process of cognition or perception. Intuitively, perception is composed of smaller yet more specific subcategories, i.e., sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch, whereas cognition consists of merely reasoning and recollection. The below method, which is used to calculate the reliability of a primary process, namely perception and cognition, may be applied to the aforementioned subcategories or any arbitrarily chosen category as well. 9 Since there are infinitely many scenarios where each of which has distinct quantity of illumination, it may be argued that there are still infinitely many processes. Insofar as an organism’s sense of sight is limited by biological considerations, it cannot perceive infinitesimally small changes in light. Thus there is a discrete quantity, a function of the effectiveness of the organs that handle visual perception, required for an organism to perceive changes in illumination. That is, if there are two locations that are infinitesimally close to each other in terms of the degree of illumination, the two locations are effectively identical with respect to the senses of the organism. Moreover, since there is intuitively a threshold for which an organism can no longer visually perceive any objects in an environment where the degree of light is too low or high, i.e., absolute darkness or blindingly bright, there are still finitely many processes. 29 Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) In a word, the reliability of primary processes is also defined by the same function that is used to calculate the reliability of any other process. That is, the reliability of a primary process (or any subcategory of the primary process) is also defined by the function ( In this case, however, ) is the total number of tokens for that given primary process, whereas is the number of tokens that yield true beliefs. Though it is important to note that the reliability of a primary process is not the reliability of any specific process; that is, it cannot be used to determine the justificational status of a belief. To ascertain the status of a belief from the reliability of a process, the specification of the process must be sufficient; particularly, it must contain all relevant details affecting the success rate. Hence there is a significant difference between the reliability of primary processes and the reliability of any specific subprocess. Namely, the reliability of a primary process only serves as an estimate or indicator of the reliability of more specific process whereas the reliability of the specific process that generated a given belief is the precise quantity needed for the calculation of the justificational status of that belief. VIII. Conclusion Despite the initial tenability of Alvin Goldman’s account of epistemic justification, the generality problem undeniably challenges the ability of reliabilism to attribute justification to a doxastic attitude merely based upon the tendency of a belief-forming process to generate true rather than false beliefs. However, by redefining the reliability of belief-forming mechanisms in terms of this tendency as well as their corresponding number of instantiations, not only can accurate reliabilities be ascribed to singularly instantiated processes but the methodology by which we specify processes can now require the inclusion of only those details affecting the efficacy of the process in order to circumvent the influence of an arbitrary degree of generality. Hence the 30 Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) generality problem—a once inescapable deterioration of reliabilism—is no longer a threat to an intuitive account of epistemic justification. Appendix: The Derivation of the Reliability Equation It is important to note that the result of this derivation does not result in a concrete formula—it is merely a family of functions that includes an arbitrary constant. We determine the value of that constant by substituting our initial condition for the appropriate variables and solving. Further note that is the reliability growth rate parameter with respect to the number of occurrences and our choice of this variable is arbitrary. Thus we need to choose a that will accurately represent the growth of the function. However, before solving for the arbitrary constant and choosing , we must first solve ( the ordinary differential equation ) by the method of separation of variables since it is both linear and autonomous. Dividing and multiplying both sides by respectively yields have that ( ( ) and . Subsequently, by integrating both sides of the equation, we ) ( )) ( because ) ( ) ( ) ( By multiplying both sides by ( and simplifying we have that exponentiating both sides yields dividing by ( as well as distributing ( ) ( which can be rewritten as yields 31 )) ) and then . Next, and then also Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) from both sides and simplifying yields ( subtracting have that when both sides are divided by Furthermore, let and rate of the process and ) . Finally, we . where is the dependent variable representing success is the independent variable signifying the total number of tokens. Thus the reliability of a given belief-forming process can be modeled by ( ) Yet the above model still contains an underdetermined constant —essentially selecting the initial point of the equation—that can be determined using an arbitrary initial condition. The reliability of any when should conceivably be ; however, due to the nature of the equation, the minimum reliability must be infinitesimally larger than 0 in order to retain the characteristics of the equation in question. Hence we will assume that a reliability of equal to . Next, we will solve for using the initial condition for any when is and . Observe that ( ) and so Cross-multiplying yields us . Subtracting or ( and ). By dividing we have that 32 from both sides gives from both sides Justin Svegliato/Volume 1 (2013) Substituting the right hand side of the equation for ( in the reliability formula above yields ) or ( Now ) must be arbitrarily chosen in order to specify the slope of the graph. We let . This will cause the slope of the graph to be more gradual; that is, the rate at which the reliability increases for each will decrease and thus ( ) However, , the success rate, may be further reduced to the number of tokens that yield true beliefs divided by the total number of tokens . Thus reliability formula yields ( ) or ( ) 33 . By substituting in for in the