A PILOT STUDY ON THE INFLUENCE OF REGULATED MEAL PLAN... ON STUDENT FOOD PURCHASING AND DINING BEHAVIORS

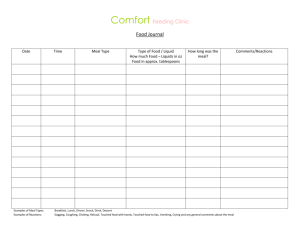

advertisement