An Evaluation of Novel Lipid-Enveloped Nanoparticles for

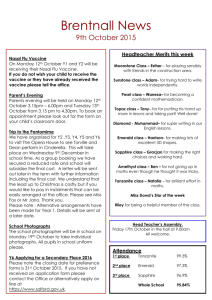

advertisement