Health and Utilization Effects of Expanding Public Health Insurance

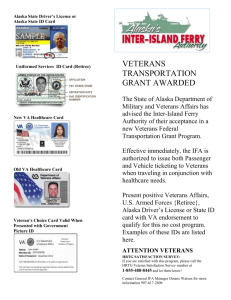

advertisement